n our MAINLINES collection, we feature locomotives and rolling stock in both passenger and freight service from mainline operations across the southern and eastern United States. Major portions of this collection date back to the steam-to-diesel transition era of the late 1950s and 60s, including several collections of "fallen flags" — mainline and regional roads that went defunct or were eventually absorbed into larger Class 1 mainline systems. Our contemporary collections feature Amtrak, CSX Transportation, and Norfolk Southern, as well as other current mainlines and regionals in the southern and eastern United States. Join HawkinsRails trackside and watch for those green signals!

n our MAINLINES collection, we feature locomotives and rolling stock in both passenger and freight service from mainline operations across the southern and eastern United States. Major portions of this collection date back to the steam-to-diesel transition era of the late 1950s and 60s, including several collections of "fallen flags" — mainline and regional roads that went defunct or were eventually absorbed into larger Class 1 mainline systems. Our contemporary collections feature Amtrak, CSX Transportation, and Norfolk Southern, as well as other current mainlines and regionals in the southern and eastern United States. Join HawkinsRails trackside and watch for those green signals!

collection

Featured Fallen Flags

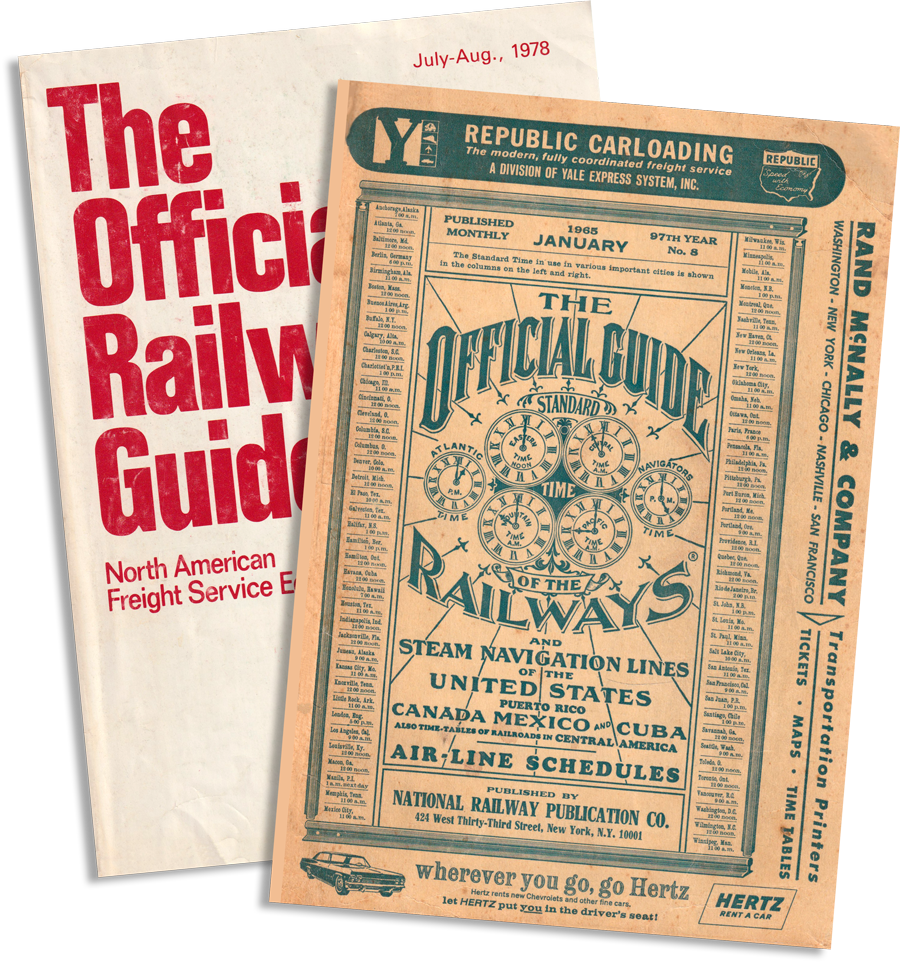

he term "Fallen Flag" first appeared in TRAINS magazine in 1974, as the title for a series of thumbnail histories of merged-away railroads. The series began with the Wabash, and employed the road’s flag emblem outline to illustrate the series’ opening pages.

he term "Fallen Flag" first appeared in TRAINS magazine in 1974, as the title for a series of thumbnail histories of merged-away railroads. The series began with the Wabash, and employed the road’s flag emblem outline to illustrate the series’ opening pages.

J. David Ingles

In railroading, a fallen flag is the term for a railroad company that has ceased to operate, either through bankruptcy, merger, acquisition, or a combination of all of these. If you were to ask any rail fan, they will all have a favorite fallen flag, sometimes more than one.

Iron Trails

A fallen flag railroad is a term used in the railroad industry to describe a railroad company that is no longer in operation or has merged with other companies. This term is derived from the practice of displaying a company's flag or emblem on the side of its locomotives and cars. When a railroad company goes out of business, its flag falls down or is taken down, hence the term "fallen flag."

TrainTracksHQ

verywhere the railroad went, it created something as if by magic. The British had invented the railroad, had figured out how to make it work. But they were aghast at what Americans did with their invention. Mostly using the same gauge as the British railroads, Americans were more generous with the loading gauge, making it possible to build enormous locomotives (too big to be safe, they said in England). Furthermore, these crazy Americans built lines to everywhere — even to nowhere at all. Nobody in Europe would have dreamed of building a railroad into uninhabited territory. You had to have two great metropolises — Birmingham and Manchester, let's say. But Americans believed in this agency of growth, saw it as a way of creating their civilization from nothing, and laid tracks into the wide open spaces. And then, where the railroad went, settlers immediately followed.

verywhere the railroad went, it created something as if by magic. The British had invented the railroad, had figured out how to make it work. But they were aghast at what Americans did with their invention. Mostly using the same gauge as the British railroads, Americans were more generous with the loading gauge, making it possible to build enormous locomotives (too big to be safe, they said in England). Furthermore, these crazy Americans built lines to everywhere — even to nowhere at all. Nobody in Europe would have dreamed of building a railroad into uninhabited territory. You had to have two great metropolises — Birmingham and Manchester, let's say. But Americans believed in this agency of growth, saw it as a way of creating their civilization from nothing, and laid tracks into the wide open spaces. And then, where the railroad went, settlers immediately followed.

George H. Douglas / All Aboard! The Railroad in American Life

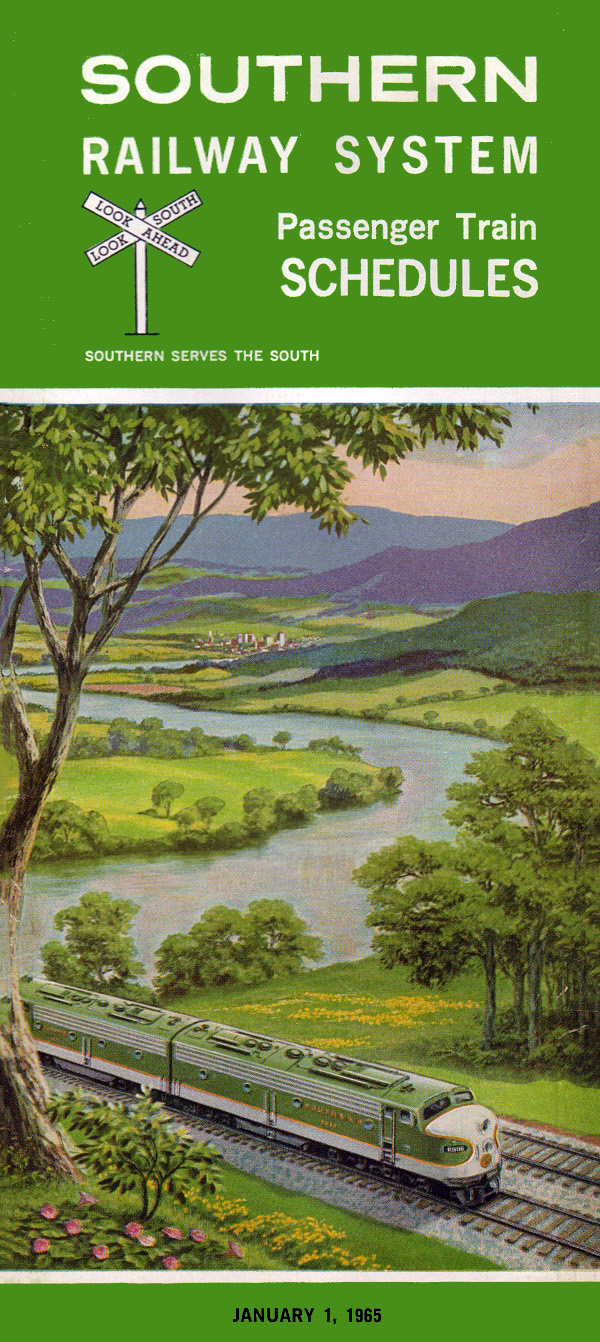

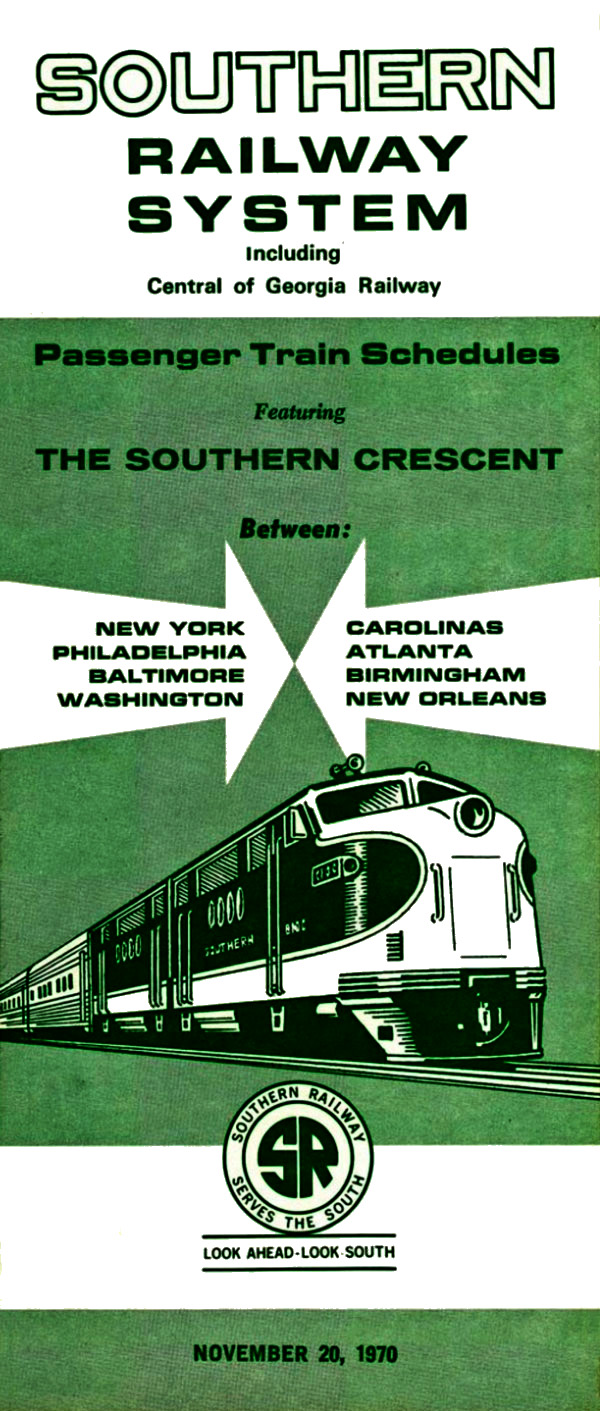

Bay Windows

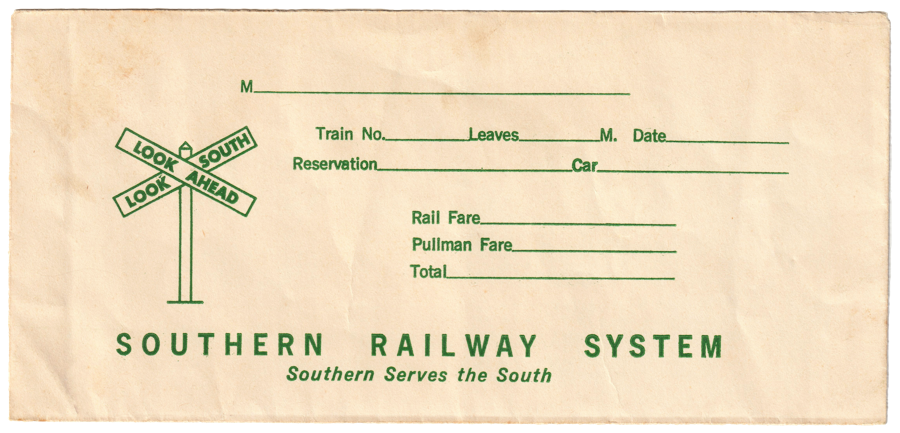

ntil the Norfolk Southern merger, every Southern Railway freight train had a bright red bay window caboose bringing up the rear. The specific angular style of these cars was distinctly Southern, and every one racked up thousands of miles all over the system. When the merger came and cabooses were no longer required by law, many of the Southern's numerous bays found retirement homes on display in municipalities, parks, and museums. A few still operate in shortline and tourist operations. Given that we are lifelong Southern fans, HawkinsRails has set out to document every known surviving Southern bay window. Look Ahead — Look South!

ntil the Norfolk Southern merger, every Southern Railway freight train had a bright red bay window caboose bringing up the rear. The specific angular style of these cars was distinctly Southern, and every one racked up thousands of miles all over the system. When the merger came and cabooses were no longer required by law, many of the Southern's numerous bays found retirement homes on display in municipalities, parks, and museums. A few still operate in shortline and tourist operations. Given that we are lifelong Southern fans, HawkinsRails has set out to document every known surviving Southern bay window. Look Ahead — Look South!

Featured Contemporary

Mainline Family Trees

he present North American railway network has its origins in thousands of railroad companies that over the years have been melded together in various ways to form seven vast freight railways, hundreds of short-line and regional systems, and a host of publicly funded passenger networks. As railroads have come together, new corporate banners have replaced classic railroad names. For example, today's CSXT represents routes formerly operated by more than a dozen classic late-steam-era railroads, including companies as varied as the old Monon, Western Maryland, and Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac. While the large railroads have swallowed up most of the old lines, a few classic names survive. Florida East Coast has served essentially the same route since the end of steam. Though FEC is owned by a major corporation, it hasn't been blended into one of the massive railroad networks. Other classic railroad names survive solely on paper or exist as latent components of larger systems.

he present North American railway network has its origins in thousands of railroad companies that over the years have been melded together in various ways to form seven vast freight railways, hundreds of short-line and regional systems, and a host of publicly funded passenger networks. As railroads have come together, new corporate banners have replaced classic railroad names. For example, today's CSXT represents routes formerly operated by more than a dozen classic late-steam-era railroads, including companies as varied as the old Monon, Western Maryland, and Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac. While the large railroads have swallowed up most of the old lines, a few classic names survive. Florida East Coast has served essentially the same route since the end of steam. Though FEC is owned by a major corporation, it hasn't been blended into one of the massive railroad networks. Other classic railroad names survive solely on paper or exist as latent components of larger systems.

Brian Solomon / North American Railroad Family Trees:

Industry's Mergers and Evolution

Featured Family Tree

Rebel Routes

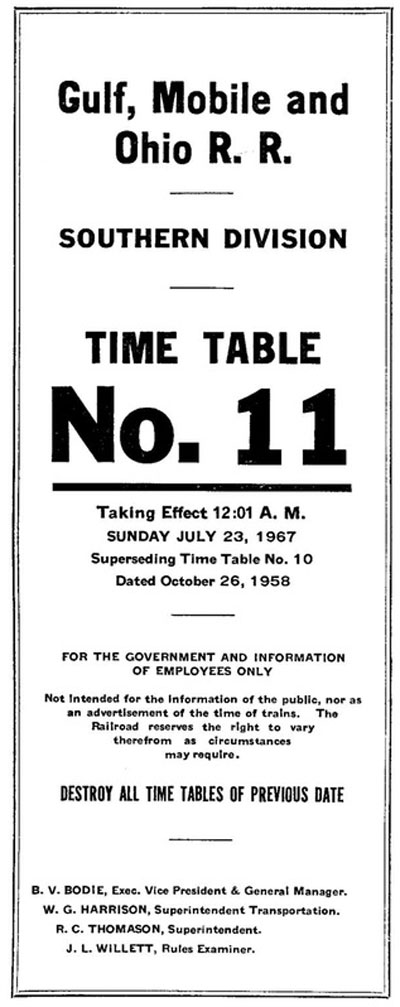

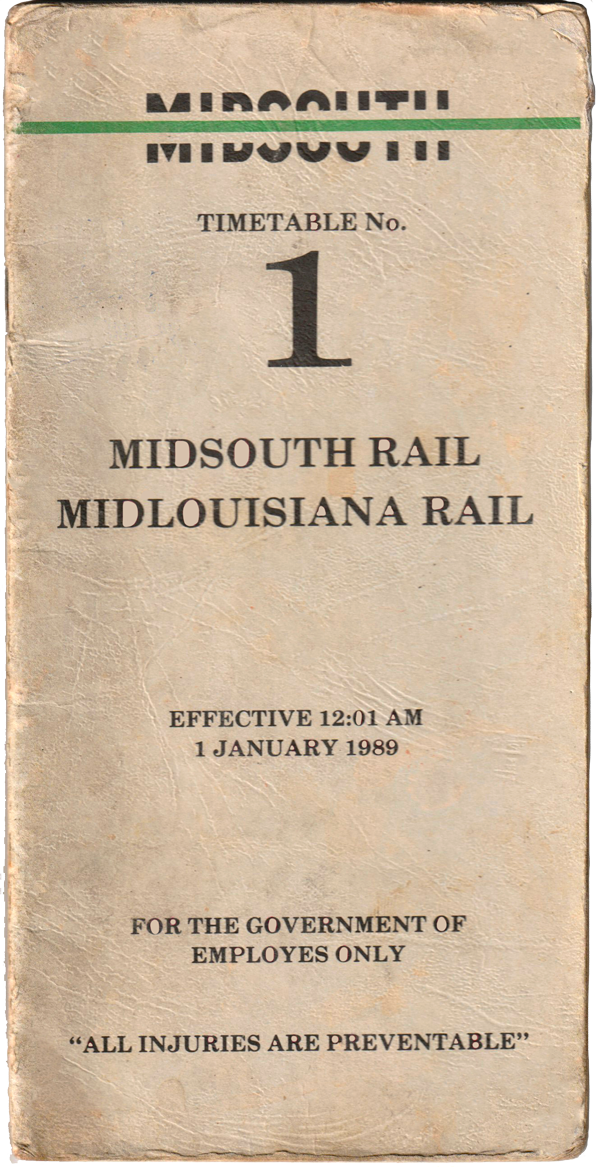

ur

HawkinsRails

roots are firmly planted in the Deep South — especially in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama. As such, we've always had a keen interest in the southern ends of the Gulf Mobile & Ohio and Illinois Central north-south mainlines. This interest includes their corporate predecessors and their many successors: mainlines, regionals, and shortline spinoffs. That's why we've gathered all our images and materials here in this Rebel Routes family tree collection. Old times here are not forgotten!

ur

HawkinsRails

roots are firmly planted in the Deep South — especially in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama. As such, we've always had a keen interest in the southern ends of the Gulf Mobile & Ohio and Illinois Central north-south mainlines. This interest includes their corporate predecessors and their many successors: mainlines, regionals, and shortline spinoffs. That's why we've gathered all our images and materials here in this Rebel Routes family tree collection. Old times here are not forgotten!

See also our Rebel Routes featured Shortlines and Preservation collections

Featured Regionals

Steam Era

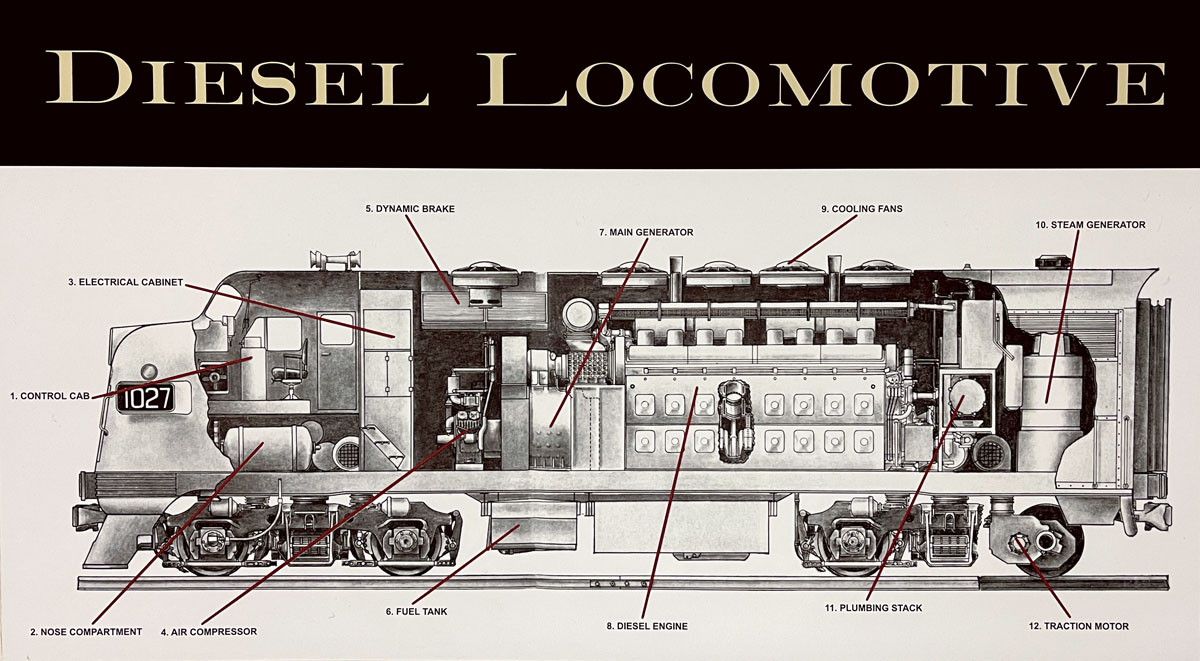

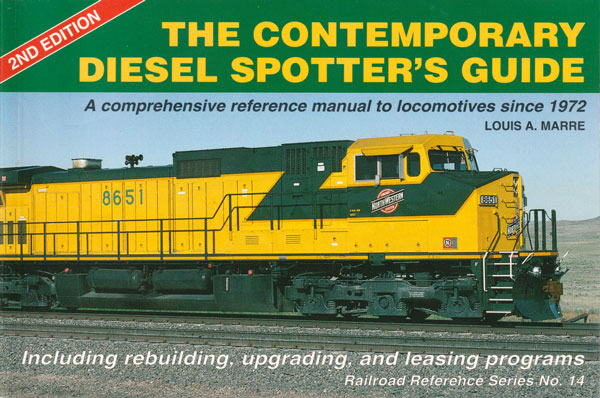

Diesel Era

ndustrialization requires a transportation system that allows the efficient movement of raw materials to factories and of finished goods to markets. There was no such system in the United States in its early years, and thus there was no domestic market extensive enough to justify large-scale production. But efforts were under way that would ultimately remove the transportation obstacle. In river transportation, a new era began with the development of the steamboat. Meanwhile, the era that would become known as the turnpike era had begun too; toll roads ran from town to town. Although the railroads played but a secondary role in America's transportation system in the 1820's and 30's, the work of the railroad pioneers became the basis for the great mid-century surge of railroad building that would link the nation together as never before. Railroads eventually became the nation's number one transportation system, and remained so until the construction of the interstate highway system halfway during the twentieth century.

ndustrialization requires a transportation system that allows the efficient movement of raw materials to factories and of finished goods to markets. There was no such system in the United States in its early years, and thus there was no domestic market extensive enough to justify large-scale production. But efforts were under way that would ultimately remove the transportation obstacle. In river transportation, a new era began with the development of the steamboat. Meanwhile, the era that would become known as the turnpike era had begun too; toll roads ran from town to town. Although the railroads played but a secondary role in America's transportation system in the 1820's and 30's, the work of the railroad pioneers became the basis for the great mid-century surge of railroad building that would link the nation together as never before. Railroads eventually became the nation's number one transportation system, and remained so until the construction of the interstate highway system halfway during the twentieth century.

Marieke Van Ophem / The Iron Horse

All Mainlines

All Mainline Collections

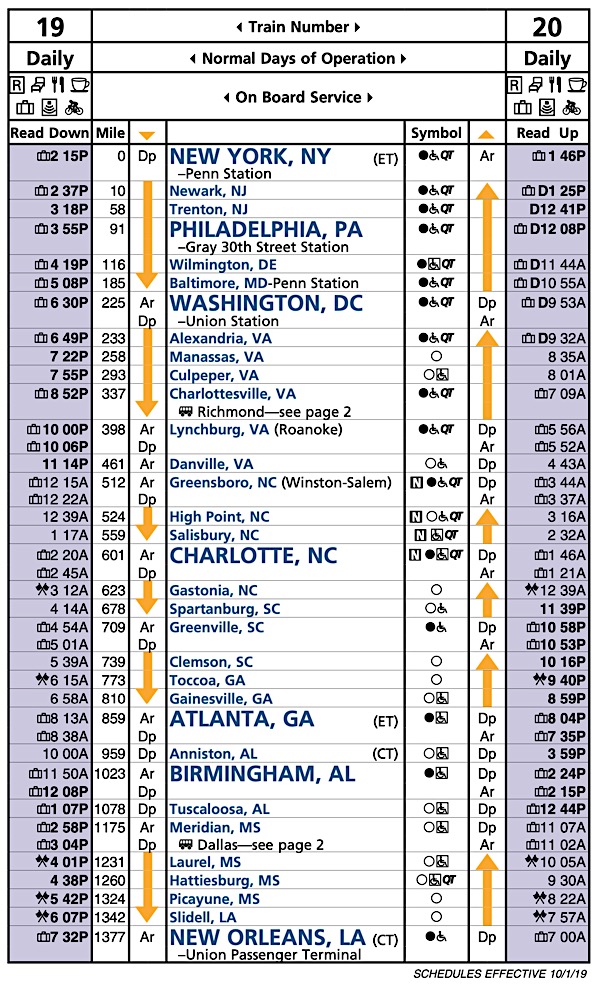

- Amtrak

- Bessemer & Lake Erie

- Buffalo & Pittsburgh

- Canadian National

- Central of Georgia

- Clinchfield

- CSX Transportation

- Denver, Rio Grande & Western

- Florida East Coast

- Frisco

- Gulf & Mississippi

- Gulf, Mobile & Northern

- Gulf, Mobile & Ohio

- Illinois Central 1

- Illinois Central Gulf

- Illinois Central 2

- Kansas City Southern

- Louisville & Nashville

Lagniappe

collection

Links

- Diesel Shop rosters for Mainline and Regional railroads

- Wikipedia article on Rail Transportation in the United States

- Association of American Railroads

- Wikipedia list of common carrier freight railroads in the United States

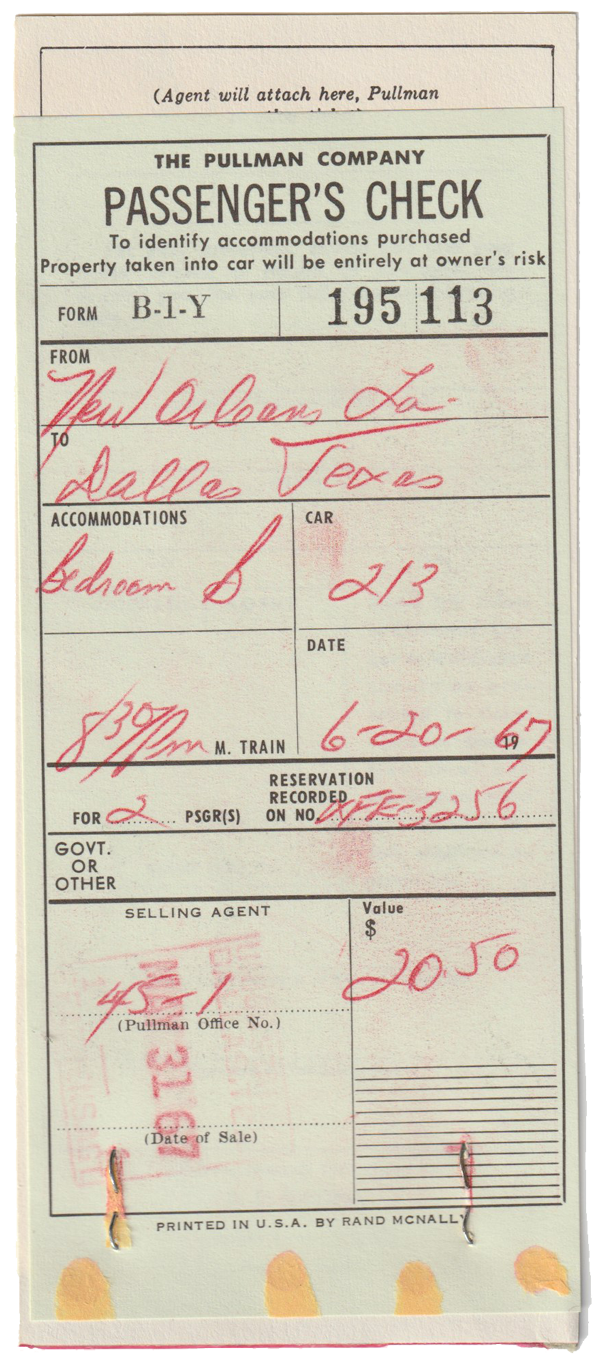

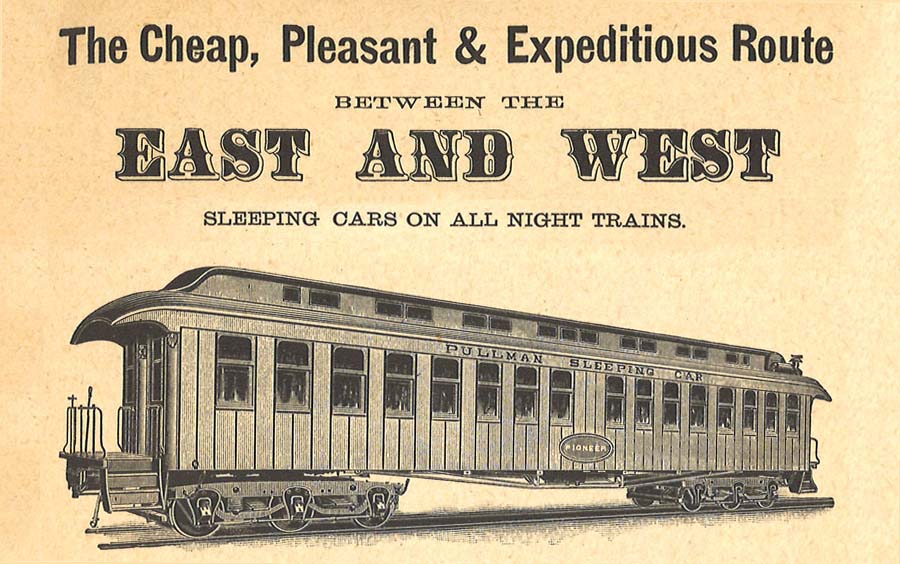

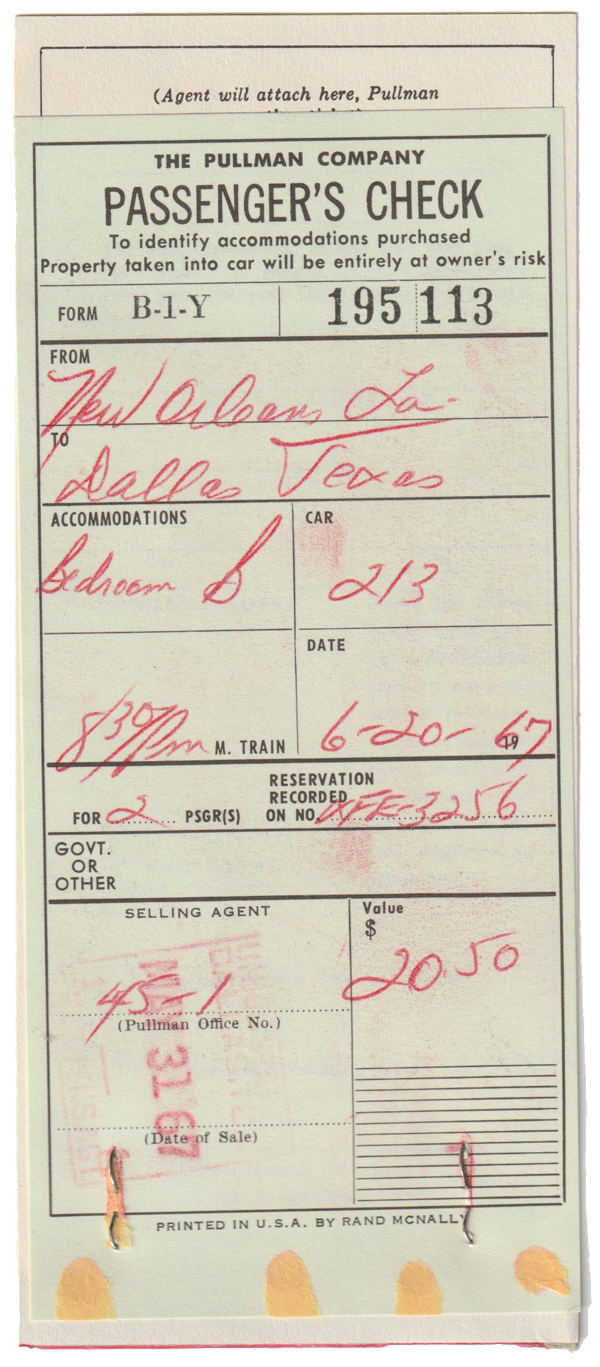

iding on trains is to him an essentially esthetic satisfaction. He sleeps better in a Pullman than at home. He admires inordinately the ingenuity of their washroom appliances and all the internal economy of the car builders' devising. He is soothed by the cornfields of Iowa or alarmed by the Colorado Rockies when viewed from the lounge of the Forty-niner or the Exposition Flyer. He eats prodigiously in the restaurant car of the Super-Chief and he is gentled and delighted by brews, vintages and strong waters on anything from the Congregational Limited to the Daylight. These are the softer and sissier aspects of his devotion.

iding on trains is to him an essentially esthetic satisfaction. He sleeps better in a Pullman than at home. He admires inordinately the ingenuity of their washroom appliances and all the internal economy of the car builders' devising. He is soothed by the cornfields of Iowa or alarmed by the Colorado Rockies when viewed from the lounge of the Forty-niner or the Exposition Flyer. He eats prodigiously in the restaurant car of the Super-Chief and he is gentled and delighted by brews, vintages and strong waters on anything from the Congregational Limited to the Daylight. These are the softer and sissier aspects of his devotion.

ow as the train bears west,

ow as the train bears west,

hen I was a boy

hen I was a boy