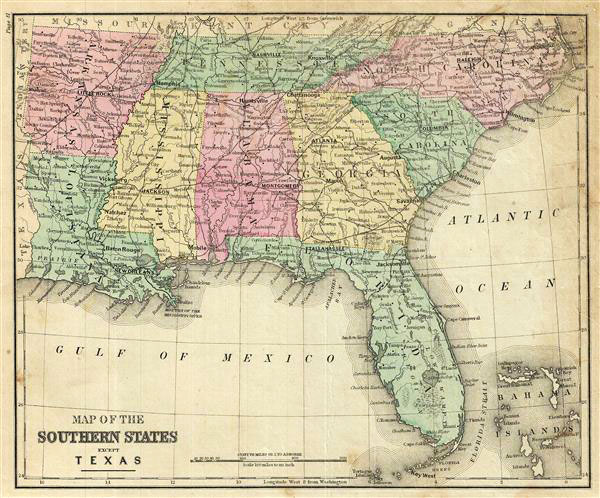

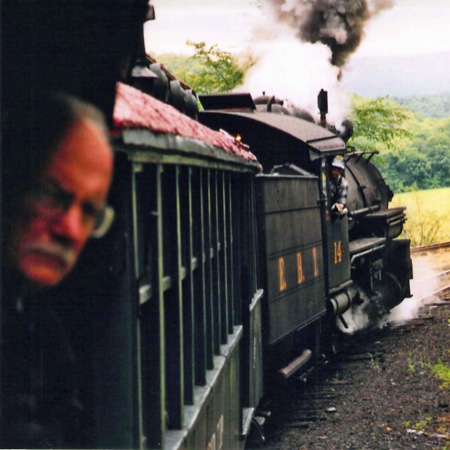

n our first collection, we feature STEAM locomotive photographs pulled from John's assortment of monochrome 120 negatives and from Ralph's adventures riding tourist railroads. Most of our black and white images date back to the transition era, when steam locomotion was giving way to diesel-electric motive power on shortlines around the southeast. Other images feature steam kettles soldiering on in museum collections or active tourist-hauling service. Special attention is given to southeastern steam excursion programs of the Southern Railway, the Norfolk Southern, and associated groups. Other collections include Deep South shortlines, industrials, and some southern mainlines. Here at HawkinsRails, we love a steam engine, cold or hot. Hear those whistles blow!

n our first collection, we feature STEAM locomotive photographs pulled from John's assortment of monochrome 120 negatives and from Ralph's adventures riding tourist railroads. Most of our black and white images date back to the transition era, when steam locomotion was giving way to diesel-electric motive power on shortlines around the southeast. Other images feature steam kettles soldiering on in museum collections or active tourist-hauling service. Special attention is given to southeastern steam excursion programs of the Southern Railway, the Norfolk Southern, and associated groups. Other collections include Deep South shortlines, industrials, and some southern mainlines. Here at HawkinsRails, we love a steam engine, cold or hot. Hear those whistles blow!

collection

collection

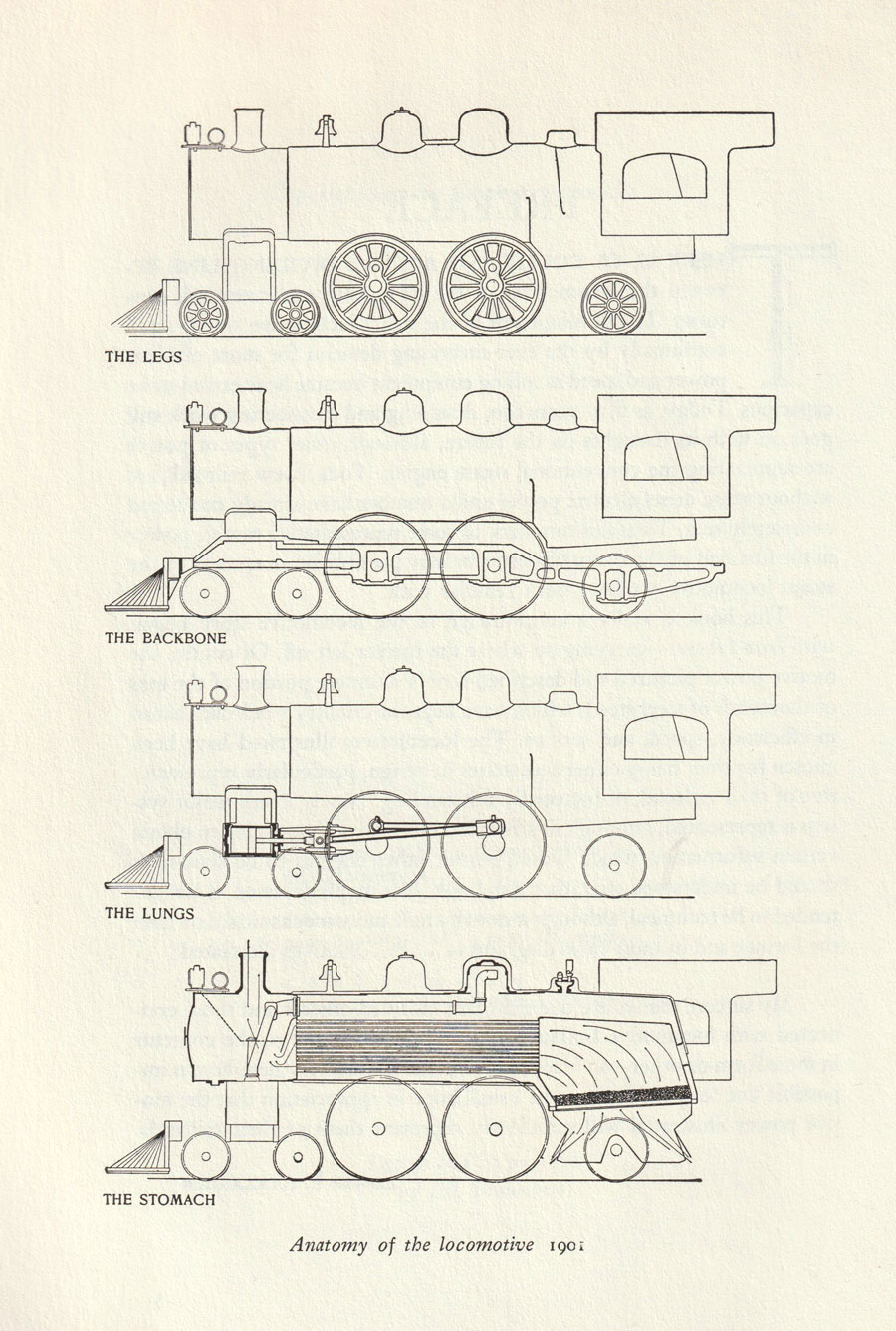

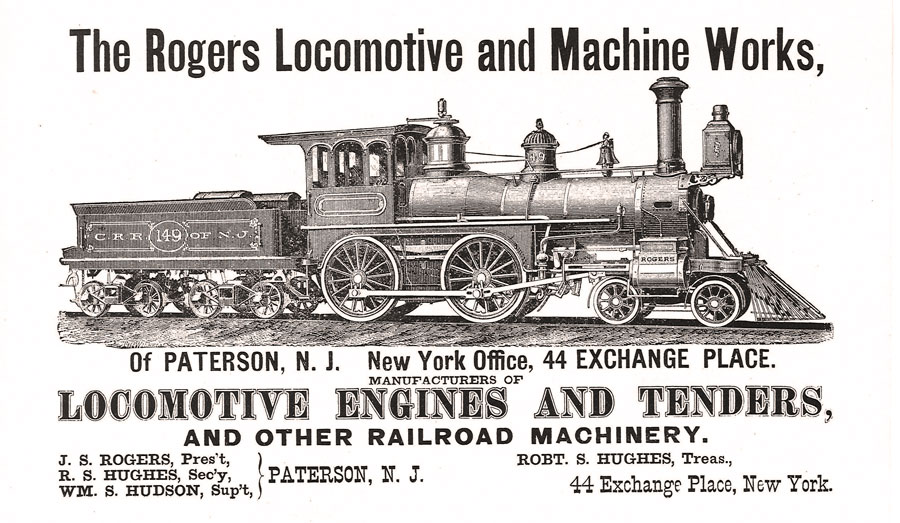

he formula for steam dawned upon man before Santa Anna took the Alamo, yet so correct if simple was the prescription that is has endured without — indeed, even resisted — change ever since. Its central component is a horizontal firetube boiler with a firebox under one end and a smokestack atop the other. This steam generator is mounted on a frame bracketed up front by a pair of cylinders coupled by main and side rods to flanged wheels which track on rails below. Fire and water do the rest. Steam! How prosaic the compound (11.188 percent hydrogen and 88.812 percent oxygen tempered by British thermal units), how wondrous the consequence. The formula works. Those possessed of engineering credentials can explain why, at least to their satisfaction. I know not why. I am confounded that this fire-breathing, rod-flailing creature of overbearing center of gravity can march down rails clutched only by thumbnail driver flanges and not only fail either to derail or to pound itself to pieces, but negotiate curves, make time, and pull 40 times its weight. But firsthand experience tells me the formula works.

he formula for steam dawned upon man before Santa Anna took the Alamo, yet so correct if simple was the prescription that is has endured without — indeed, even resisted — change ever since. Its central component is a horizontal firetube boiler with a firebox under one end and a smokestack atop the other. This steam generator is mounted on a frame bracketed up front by a pair of cylinders coupled by main and side rods to flanged wheels which track on rails below. Fire and water do the rest. Steam! How prosaic the compound (11.188 percent hydrogen and 88.812 percent oxygen tempered by British thermal units), how wondrous the consequence. The formula works. Those possessed of engineering credentials can explain why, at least to their satisfaction. I know not why. I am confounded that this fire-breathing, rod-flailing creature of overbearing center of gravity can march down rails clutched only by thumbnail driver flanges and not only fail either to derail or to pound itself to pieces, but negotiate curves, make time, and pull 40 times its weight. But firsthand experience tells me the formula works.

David P. Morgan / 1968

Anniston, Al / Nov 1969 / JCH

'm one of these people who likes to see old-timey machinery operate, so I enjoy seeing a well-maintained, preserved and restored automobile, truck, or a locomotive — whatever it is, operating. When I was a kid, most of the time when you rode a steam train around here [in New Orleans] you rode in a non air-conditioned coach, and if it was summertime you'd have the windows open and the soot would come in. The Louisville & Nashville, the Illinois Central, and the Southern all burned coal; those were the three main railroads that I would ride on. And so you'd get smoke and cinders all in your eyes! In the wintertime, with the windows closed, it was much more comfortable. The car would be warm in the winter because they'd have steam heat in the train.

'm one of these people who likes to see old-timey machinery operate, so I enjoy seeing a well-maintained, preserved and restored automobile, truck, or a locomotive — whatever it is, operating. When I was a kid, most of the time when you rode a steam train around here [in New Orleans] you rode in a non air-conditioned coach, and if it was summertime you'd have the windows open and the soot would come in. The Louisville & Nashville, the Illinois Central, and the Southern all burned coal; those were the three main railroads that I would ride on. And so you'd get smoke and cinders all in your eyes! In the wintertime, with the windows closed, it was much more comfortable. The car would be warm in the winter because they'd have steam heat in the train.

A steam locomotive is a fun piece of equipment to be around because it kind of lives and breathes. It can be just sitting there, and all the sudden the air compressor will just plug on, or the boiler will just let out steam when the pressure builds up. A lot of people have compared a steam engine to a man or a horse — the original nickname for locomotives years ago was the "Iron Horse" — and it kind of does seem like one at times. Not only does it pull like a horse, but when it's hard at work, when it gets down and labors, it almost has a living way about it. It's fun to be around one.

John C. Hawkins / Steam in the Big Easy

Favorites

Favorite Steam Collections

Southern Steam

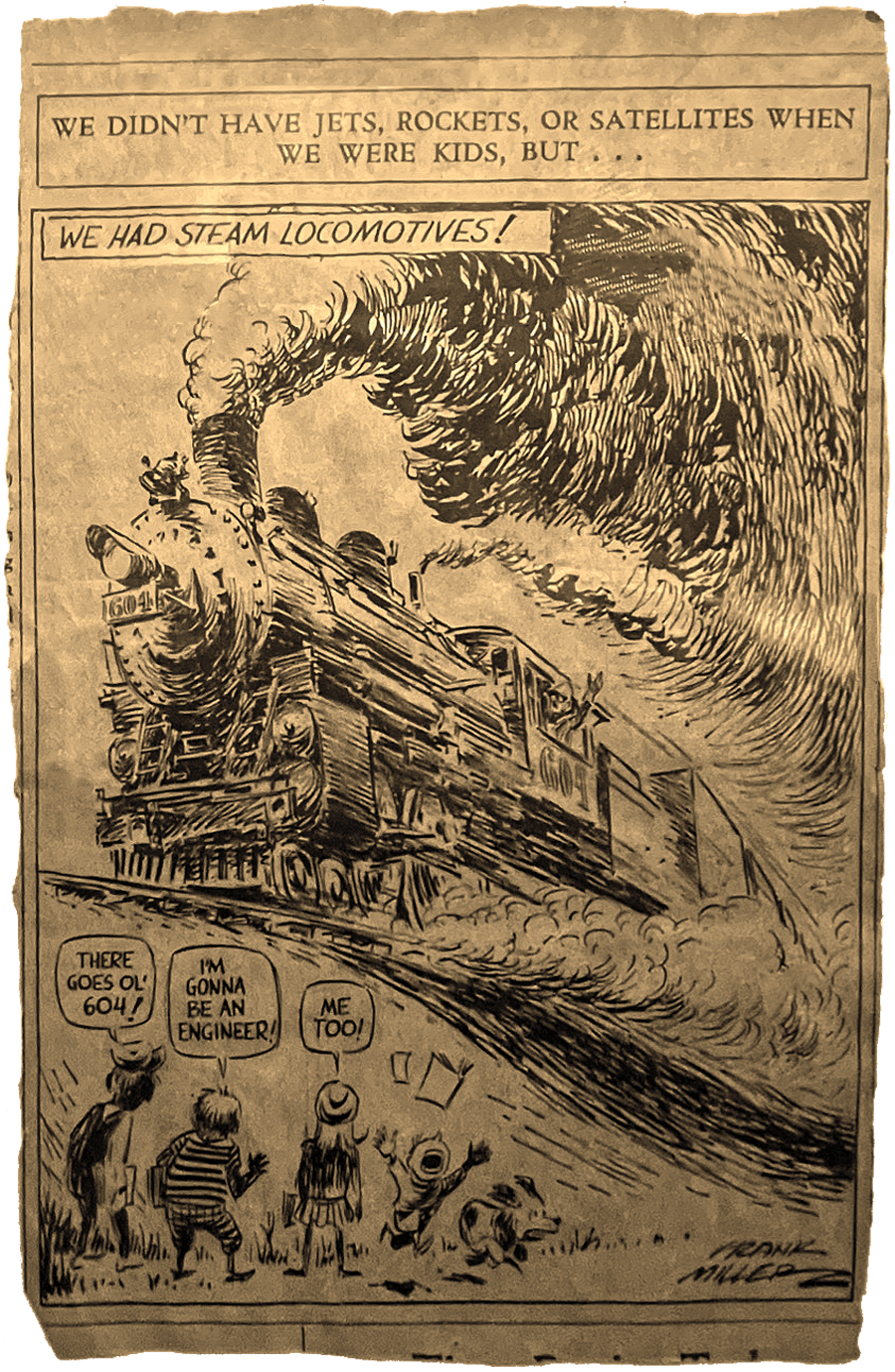

he reciprocating locomotive had served the nation well for 120 years. It had tied the economies of young seaboard cities together with endless miles of smoke ribbons. It had labored over three transcontinental mountain ranges to carry settlers west and to tap the riches of the prairies, the desert, and the deep ravines. It had introduced new concepts of speed and power, and hastened the development of an even faster means of communication — the telegraph. Overlooked, perhaps, was the fact that in wooing youngsters from both farms and urban areas to stoke its hungry maw, it had placed a country-wide accent on mechanics. Its most appealing attribute, however, was its almost human behavior. Aside from its iron belly and lungs, its pulsebeat, and its highly articulate mouthings, the locomotive was a headstrong machine from the moment it was outshopped. Its behavior was well-mannered or stubborn, depending in large measure upon the hand at the throttle. Again, some engines were avowed killers, while others would tear their hearts out on tasks beyond their capabilities. The great French novelist, Emile Zola, summed it up well when, in The Human Beast, he wrote:

he reciprocating locomotive had served the nation well for 120 years. It had tied the economies of young seaboard cities together with endless miles of smoke ribbons. It had labored over three transcontinental mountain ranges to carry settlers west and to tap the riches of the prairies, the desert, and the deep ravines. It had introduced new concepts of speed and power, and hastened the development of an even faster means of communication — the telegraph. Overlooked, perhaps, was the fact that in wooing youngsters from both farms and urban areas to stoke its hungry maw, it had placed a country-wide accent on mechanics. Its most appealing attribute, however, was its almost human behavior. Aside from its iron belly and lungs, its pulsebeat, and its highly articulate mouthings, the locomotive was a headstrong machine from the moment it was outshopped. Its behavior was well-mannered or stubborn, depending in large measure upon the hand at the throttle. Again, some engines were avowed killers, while others would tear their hearts out on tasks beyond their capabilities. The great French novelist, Emile Zola, summed it up well when, in The Human Beast, he wrote:

Somewhere in the course of manufacture, a hammer blow or a deft mechanic's hand imparts to a locomotive a soul of its own.

Somewhere in the course of manufacture,

a hammer blow or a deft mechanic's hand

imparts to a locomotive

a soul of its own.

Henry B. Comstock / The Iron Horse

Railroads

Railroad Collections

Mainlines

Shortlines

Industrials

hen, in the most moving of American epics "John Brown's Body," Stephen Benét wrote thunderingly of "riders shaking the heart with the hooves that will not cease, he was writing of the centaur chieftains of the Civil War. They were Sheridan, Stuart, Custer, Wheeler, Buford, Forrest, Kilpatrick, Hampton and Lee, the goodliest company of riders to shake the heart in all the history of men on horseback. But Benét might well have been alluding to another company of riders who, for a century and a half, shook the hearts of the American people as no human artifact or devising has moved or ever will move the spirits and imaginations of men.

hen, in the most moving of American epics "John Brown's Body," Stephen Benét wrote thunderingly of "riders shaking the heart with the hooves that will not cease, he was writing of the centaur chieftains of the Civil War. They were Sheridan, Stuart, Custer, Wheeler, Buford, Forrest, Kilpatrick, Hampton and Lee, the goodliest company of riders to shake the heart in all the history of men on horseback. But Benét might well have been alluding to another company of riders who, for a century and a half, shook the hearts of the American people as no human artifact or devising has moved or ever will move the spirits and imaginations of men.

Not a single generation, but five of them, as men reckon their coming and going on earth, were lifted up by the steam locomotive engine, by its sights and sounds and even its smells which laid so compulsive a hold on the national imagining that it will never entirely disappear from the national consciousness. The railroad locomotive was incomparably more an instrument of destiny than any other to which the hands of men were turned, even including the Colt's Patent Revolving Pistol. For fifteen decades "the tall, far-trafficking shapes" of American record were the smoke plumes of burning wood, coal and oil that moved with compulsive majesty across the summer horizons of a nation bound on mighty landfarings. They were the tangible symbols and oriflamme of a universal preoccupation with movement and the realization of a continental dimension.

Lucius Beebe & Charles Clegg /

The Age of Steam / 1957

All Steam Collections

- Alabama Central

- Apalachicola Northern

- Bonhomie & Hattiesburg Southern

- Columbus & Greenville

- Denver, Rio Grande & Western

- Flying Scotsman

- Godchaux Sugar Cane Company

- Great Locomotive Chase

- Gulf, Mobile & Northern

- Illinois Central

- Louisiana Cypress Lumber Co.

- Louisiana Southern

- Mississippian

- Mississippian #77

- Mississippi Central

- Mobile & Ohio

- Museum steam

- New Orleans Great Northern

- Nickel Plate Road #765

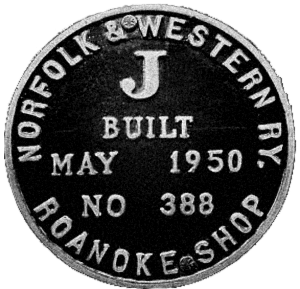

- Norfolk & Western #611

- Savannah & Atlanta #750

- Shay locomotives

- Southern Railway #630

- Southern Pacific #745

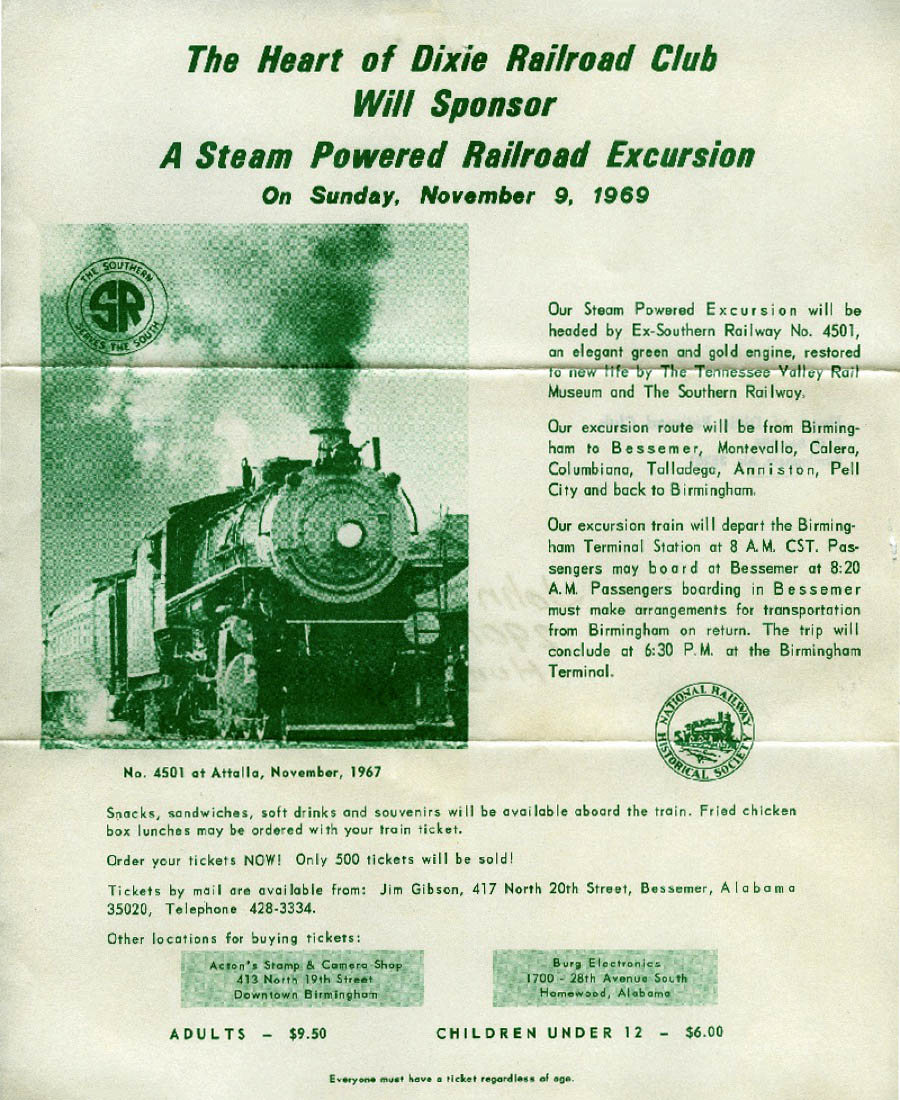

- Southern Railway #4501

- Southern Motive Power

- Southern Excursion Steam Program

- Southern Steam-o-Rama event

- Sumpter & Choctaw Railway

- T R Miller Mill Company

- Tuskegee #101

- Twin Seam Mining Company

- Tourist steam

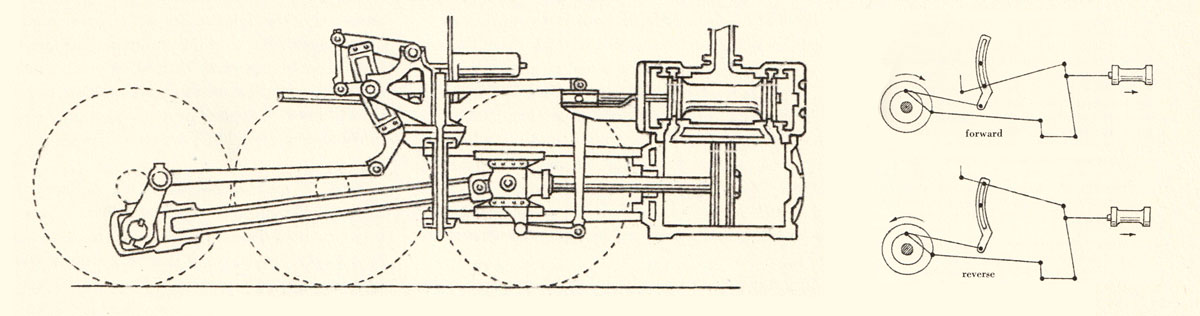

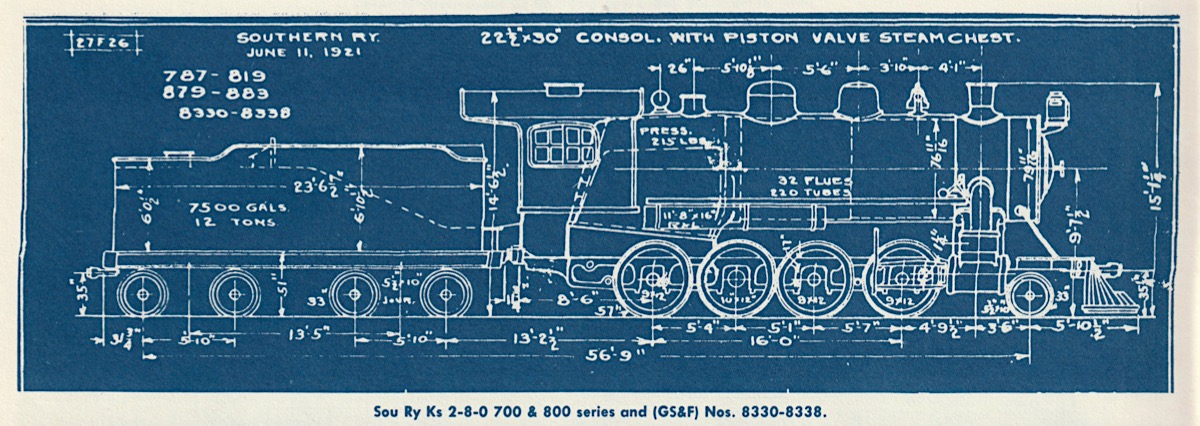

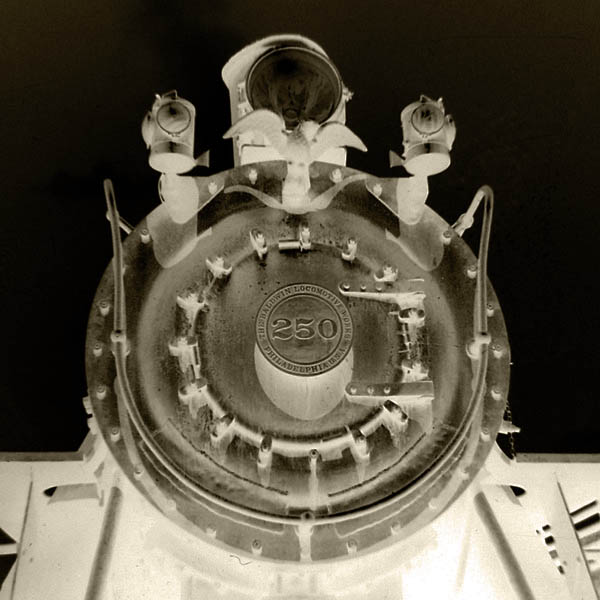

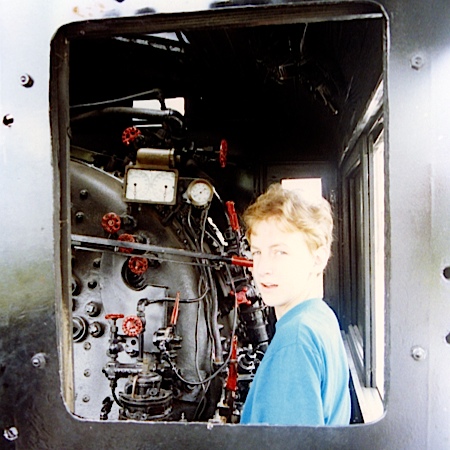

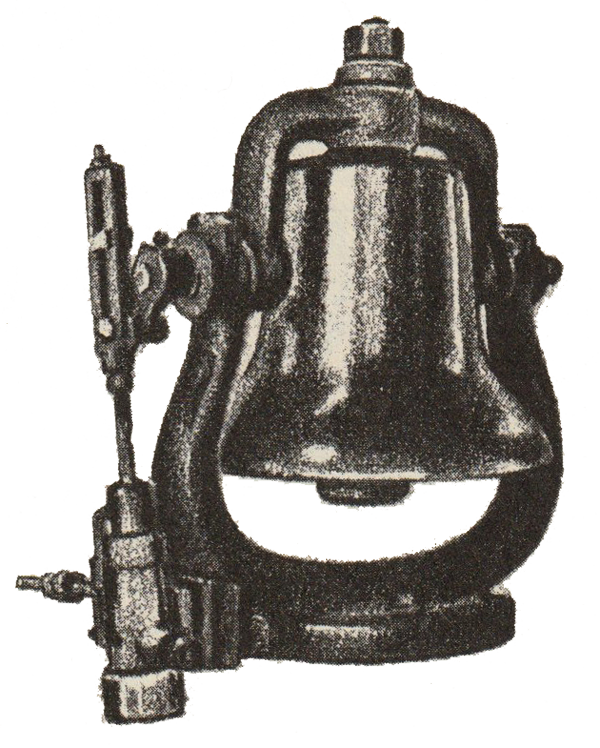

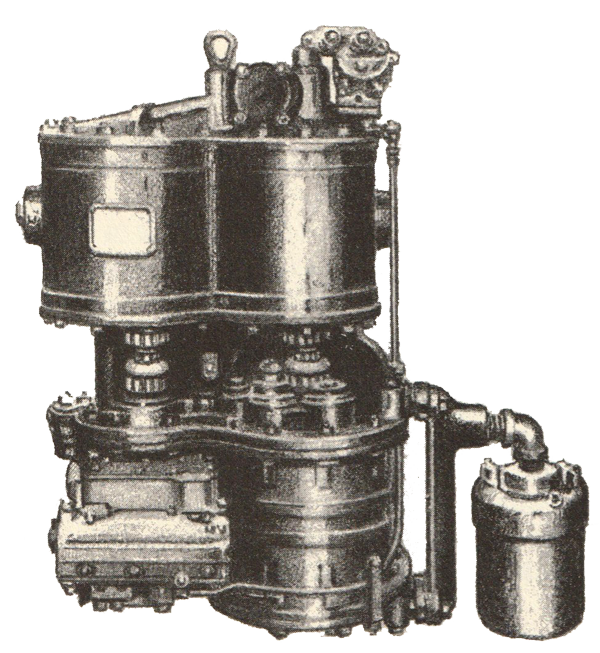

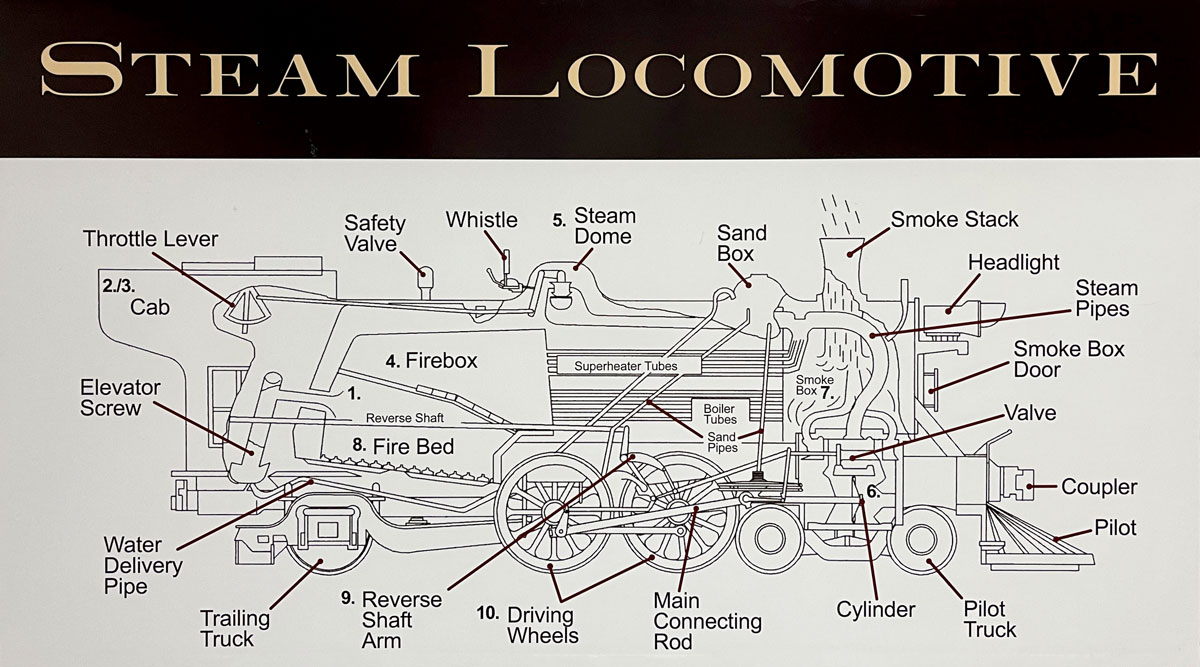

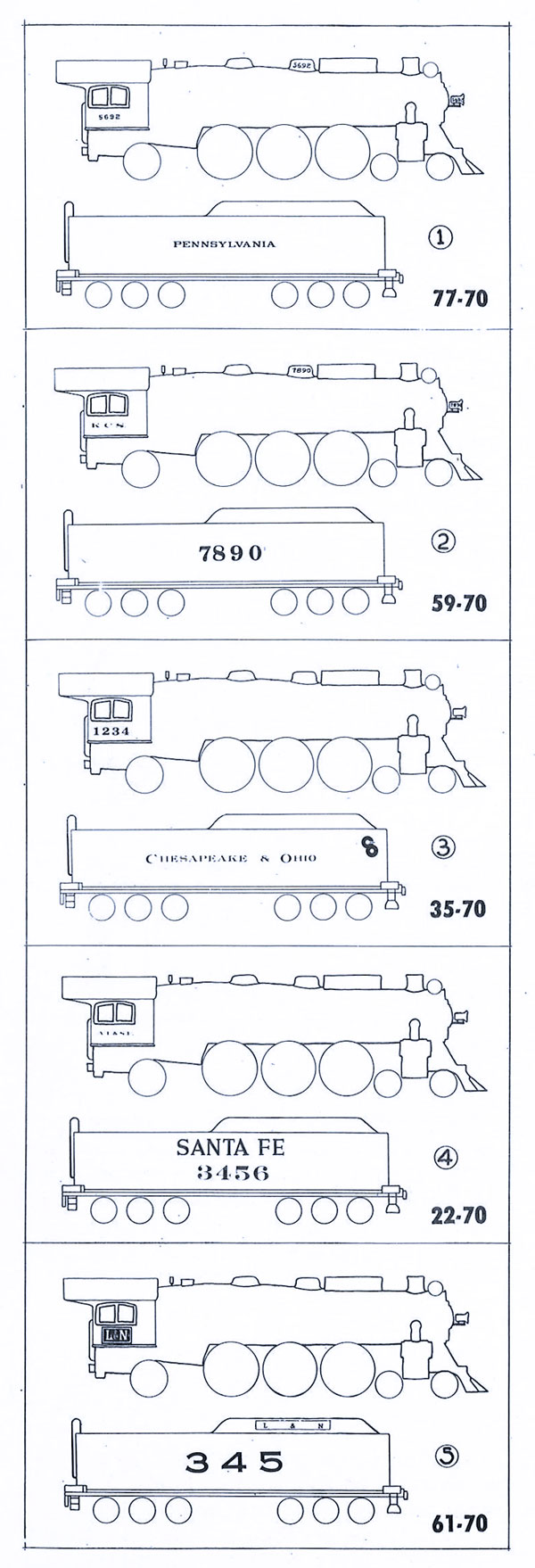

STEAM LOCOMOTIVE, generally speaking, consists of BOILER, ENGINE, and RUNNING GEAR. The boiler and the engine are mounted on a FRAME. The frame is supported by the running gear, by means of a system of equalized SPRING RIGGING. The energy in the steam in the boiler is generated from the combustion of fuel in the FIREBOX. This energy is converted into work in the CYLINDERS of the engine and is made to propel the locomotive by means of a connection between the cylinders and the DRIVING WHEELS.

STEAM LOCOMOTIVE, generally speaking, consists of BOILER, ENGINE, and RUNNING GEAR. The boiler and the engine are mounted on a FRAME. The frame is supported by the running gear, by means of a system of equalized SPRING RIGGING. The energy in the steam in the boiler is generated from the combustion of fuel in the FIREBOX. This energy is converted into work in the CYLINDERS of the engine and is made to propel the locomotive by means of a connection between the cylinders and the DRIVING WHEELS.

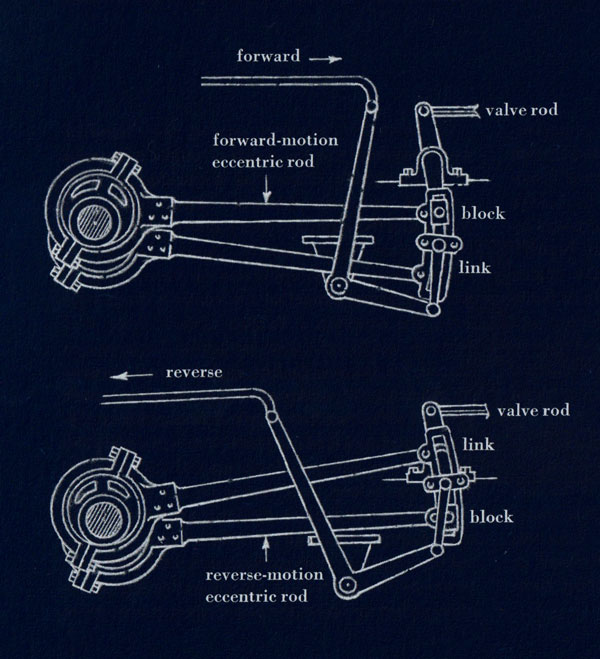

An engine such as is used in steam locomotive practice consists of a CYLINDER containing a PISTON. On the face of the piston are PACKING RINGS which spring against the walls of the cylinder, making a steamtight joint. The piston is fitted on a PISTON ROD which extends through a GLAND and stuffing box at the back head of the cylinder. The back end of the piston rod is connected to a CROSSHEAD. The crosshead moves on GuiDEs which are fastened to the cylinder at one end and to a GUIDE YOKE attached to the engine frame at the opposite end. A MAIN ROD connects the crosshead with a CRANK PIN on the MAIN DRIVING WHEEL so that, as the piston moves backward and forward in the cylinder, this back-and-forth or RECIPROCATING MOTION is changed into revolving or ROTARY MOTION at the driving wheel.

Fundamentals of a Steam Locomotive / 1949

Deep South

Steam Gallery

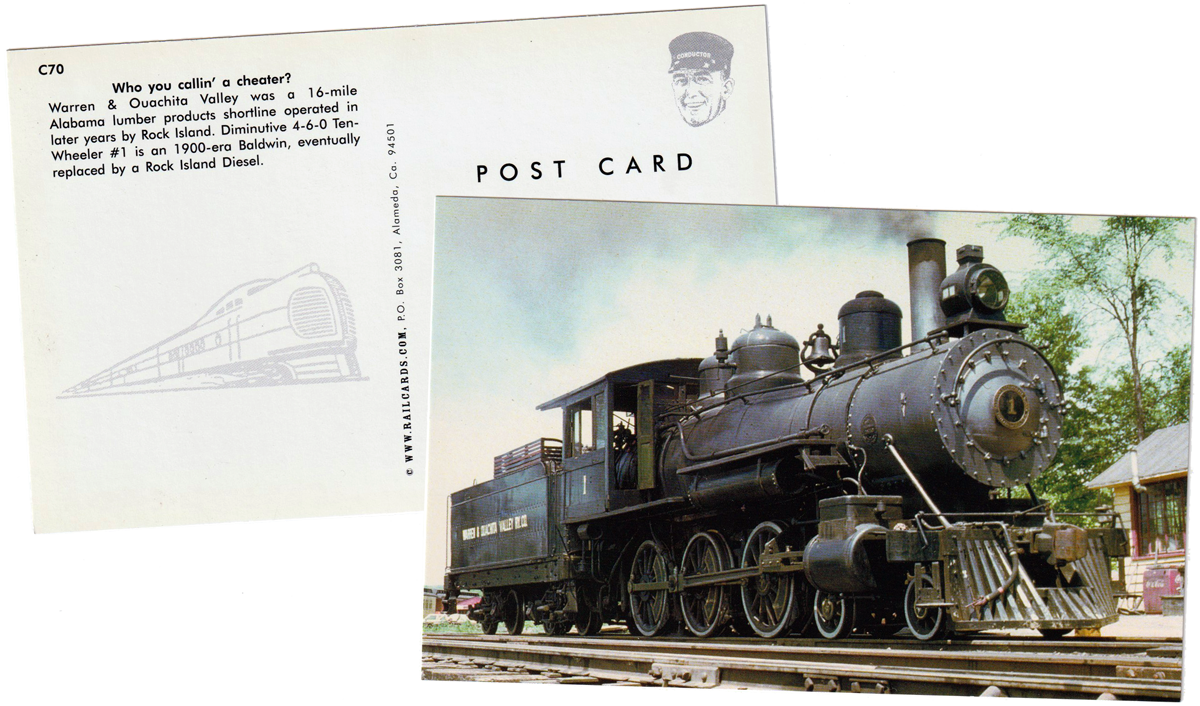

hrough the end of the Second World War the railroads of the Deep South, both main-line carriers and short lines, retained to a large degree the diversification and individuality that had long since disappeared in institutionalized uniformity elsewhere. Pearl Harbor gave many a short line a renewed lease on life, on borrowed time to be sure, and saved many an aging Mogul, Prairie, and Consolidation from the scrapper's torch. So long as war demanded gasoline and rubber, steam lived splendidly on in a never-never land of turpentine and Jim-Crow combines and trestles over dangerous but tranquil bayous. The end of the world came with peace.

hrough the end of the Second World War the railroads of the Deep South, both main-line carriers and short lines, retained to a large degree the diversification and individuality that had long since disappeared in institutionalized uniformity elsewhere. Pearl Harbor gave many a short line a renewed lease on life, on borrowed time to be sure, and saved many an aging Mogul, Prairie, and Consolidation from the scrapper's torch. So long as war demanded gasoline and rubber, steam lived splendidly on in a never-never land of turpentine and Jim-Crow combines and trestles over dangerous but tranquil bayous. The end of the world came with peace.

Lucius Beebe & Charles Clegg /

The Age of Steam / 1957

All gallery images below by John Carlton Hawkins

Railfan Beginnings

Railfan Beginnings

Tea kettle #1 (below) has little significance in and of itself, strewn as it is among the rusting appliances and scrap metal of a salvage yard along the Mississippi River near New Orleans. But relative to our photo collection, the little 0-4-0 tanker is an important specimen: She's the first locomotive my father ever photographed. The story goes that not long after purchasing their first new car in 1947, dad's family decided to go for a drive and to venture across the Mississippi River on the Huey P. Long bridge — a massive steel structure named for Louisiana's notorious governor. While following the mighty Mississippi along River Road through Westwego, Louisiana, my father — in 1948, 15 years old — spotted the loco in the Westwego Salvage yard. "It was the smallest locomotive I had ever seen," he later recalled. My grandfather pulled over to the side of the road and dad convinced my grandmother to let him take a few photos with the family's Kodak Brownie camera. Thus began a 60 year interest in railfan photography — appropriately, I suppose, with little #1.

Westwego, La / 1948 / JCH

hile there are still a few steamboats left in regular service on North American waters, comparable steam has vanished from this continent's major rails. Some of the surviving steam locomotives are on a dwindling handful of off-the-beaten-path lines where, forgotten by most of us, they have become curiosities employed in a service too marginal to warrant investment in any kind of modernity. Also, largely through the efforts of the never-say-die buffs, a few have been saved from the scrap-heap to run again on fan trips or on a score of new lines organized especially for steam excursions. However these events are more akin to antique-car meets than they are a re-creation of the days of steam railroading when the locomotive was an authentic part of our landscape and of the daily lives of its people. That era is now irrevocably gone.

hile there are still a few steamboats left in regular service on North American waters, comparable steam has vanished from this continent's major rails. Some of the surviving steam locomotives are on a dwindling handful of off-the-beaten-path lines where, forgotten by most of us, they have become curiosities employed in a service too marginal to warrant investment in any kind of modernity. Also, largely through the efforts of the never-say-die buffs, a few have been saved from the scrap-heap to run again on fan trips or on a score of new lines organized especially for steam excursions. However these events are more akin to antique-car meets than they are a re-creation of the days of steam railroading when the locomotive was an authentic part of our landscape and of the daily lives of its people. That era is now irrevocably gone.

The steam locomotive had a more far-reaching effect on the development of the continent than did any other piece of machinery. Within fifty years after its introduction it had formed a land transportation system unparalleled in history. For one brief century and a quarter it was the undisputed ruler of North America. Of all the machines by which man has harnessed the elements to produce power, none can compare, to my mind, with the steam locomotive. This successor to the beast of burden was itself a creature — a metal beast, breathing steam instead of air; a glorious beast, which hissed and sighed and roared its way across the countryside. It was alive and proud, the embodiment of sheer brute force even in repose. Its mechanism of motion — never hidden beneath a shroud as are so many of today's contrivances — was completely exposed. This openness made it uniquely comprehensible, and took away anything sinister about its nature. And naturally even more so than the casual viewer could the men who ran it and tended it feel its majestic vitality.

David Plowden / Farewell to Steam / 1966 / image JCH

Links

- Wikipedia article for Steam Locomotives

- Surviving Steam Locomotives database

- American Steam Locomotive Wheel Arrangements

- Steam Locomotive Information

- Richard Leonard's Steam Locomotive Archive

A steam locomotive is a fun piece of equipment to be around because it kind of lives and breathes. It can be just sitting there, and all the sudden the air compressor will just plug on, or the boiler will just let out steam when the pressure builds up. A lot of people have compared a steam engine to a man or a horse — the original nickname for locomotives years ago was the "Iron Horse" — and it kind of does seem like one at times. Not only does it pull like a horse, but when it's hard at work, when it gets down and labors, it almost has a living way about it. It's fun to be around one.

A steam locomotive is a fun piece of equipment to be around because it kind of lives and breathes. It can be just sitting there, and all the sudden the air compressor will just plug on, or the boiler will just let out steam when the pressure builds up. A lot of people have compared a steam engine to a man or a horse — the original nickname for locomotives years ago was the "Iron Horse" — and it kind of does seem like one at times. Not only does it pull like a horse, but when it's hard at work, when it gets down and labors, it almost has a living way about it. It's fun to be around one.

ooser called from Nebraska

ooser called from Nebraska

Not a single generation, but five of them, as men reckon their coming and going on earth, were lifted up by the steam locomotive engine, by its sights and sounds and even its smells which laid so compulsive a hold on the national imagining that it will never entirely disappear from the national consciousness. The railroad locomotive was incomparably more an instrument of destiny than any other to which the hands of men were turned, even including the Colt's Patent Revolving Pistol. For fifteen decades "the tall, far-trafficking shapes" of American record were the smoke plumes of burning wood, coal and oil that moved with compulsive majesty across the summer horizons of a nation bound on mighty landfarings. They were the tangible symbols and oriflamme of a universal preoccupation with movement and the realization of a continental dimension.

Not a single generation, but five of them, as men reckon their coming and going on earth, were lifted up by the steam locomotive engine, by its sights and sounds and even its smells which laid so compulsive a hold on the national imagining that it will never entirely disappear from the national consciousness. The railroad locomotive was incomparably more an instrument of destiny than any other to which the hands of men were turned, even including the Colt's Patent Revolving Pistol. For fifteen decades "the tall, far-trafficking shapes" of American record were the smoke plumes of burning wood, coal and oil that moved with compulsive majesty across the summer horizons of a nation bound on mighty landfarings. They were the tangible symbols and oriflamme of a universal preoccupation with movement and the realization of a continental dimension.