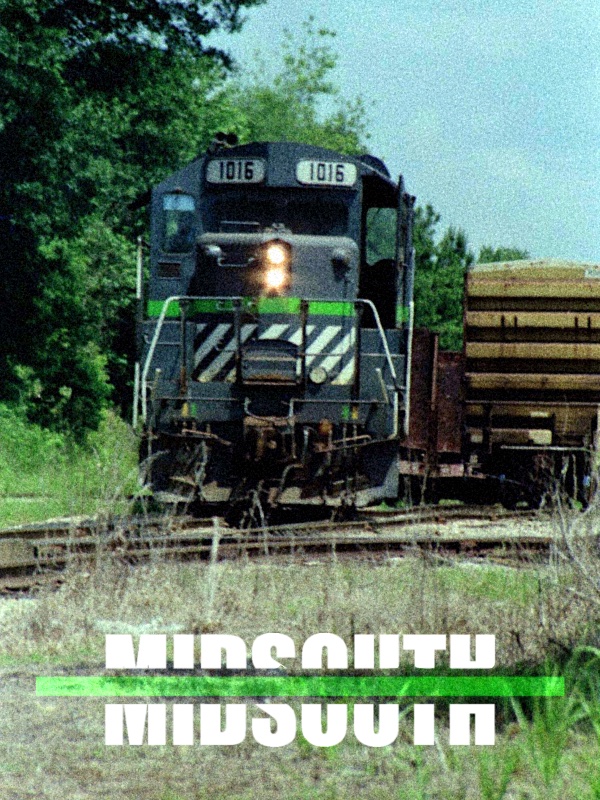

MidSouth Rail

Building Block of the Meridian Speedway

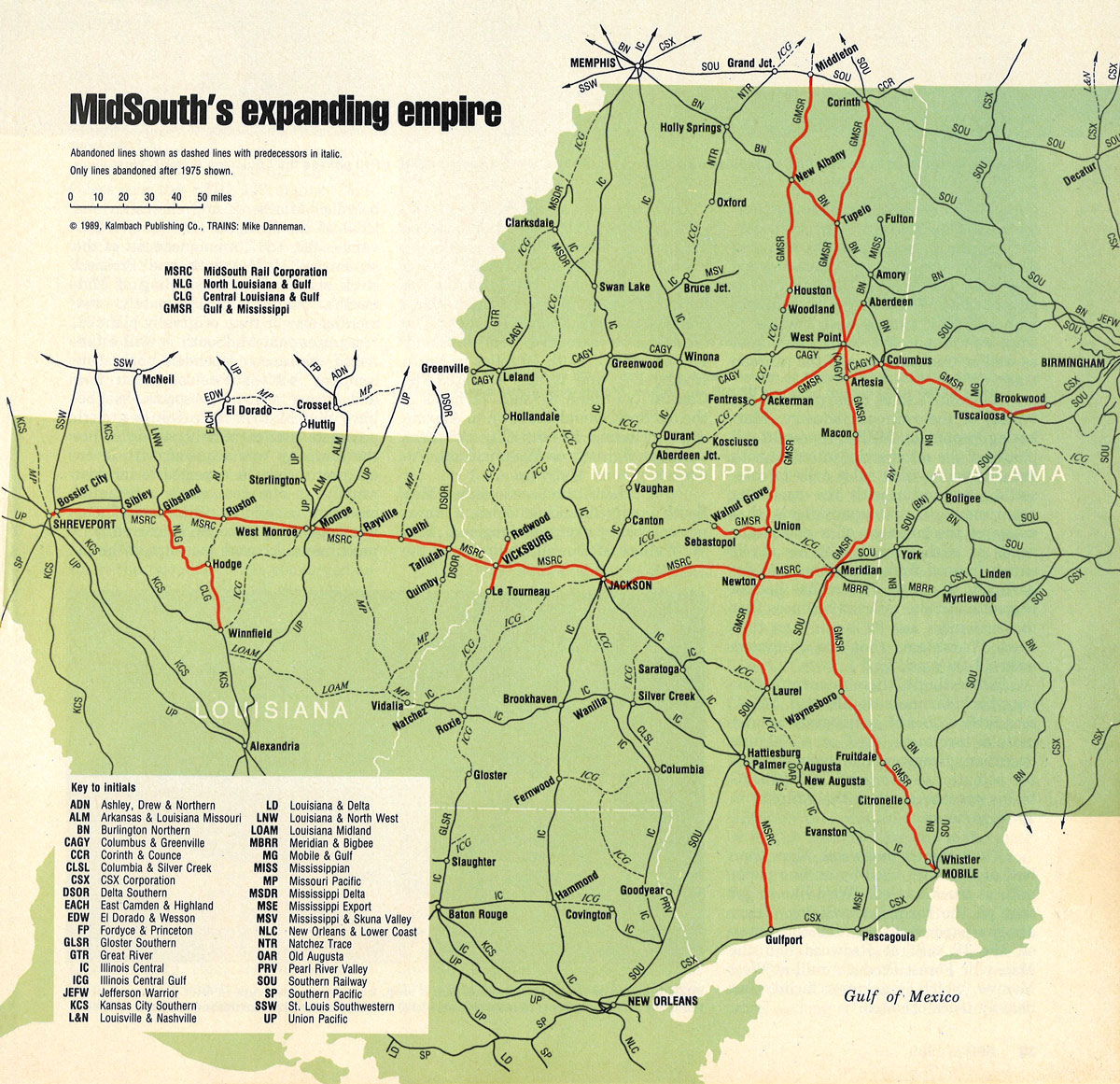

Created in 1986 and then acquired by 1994, the MidSouth Rail Corporation proved to be an 8-year study in how to run a successful Staggers-era regional spinoff. MidSouth purchased a unwanted Illinois Central Gulf secondary, along with a few dozen well-travelled Paducah rebuilds, and by rehabilitating both assets created a prosperous east-west regional that became the backbone for today's efficient "Meridian Speedway" — a vital freight linkage between eastern and midwestern traffic centers.

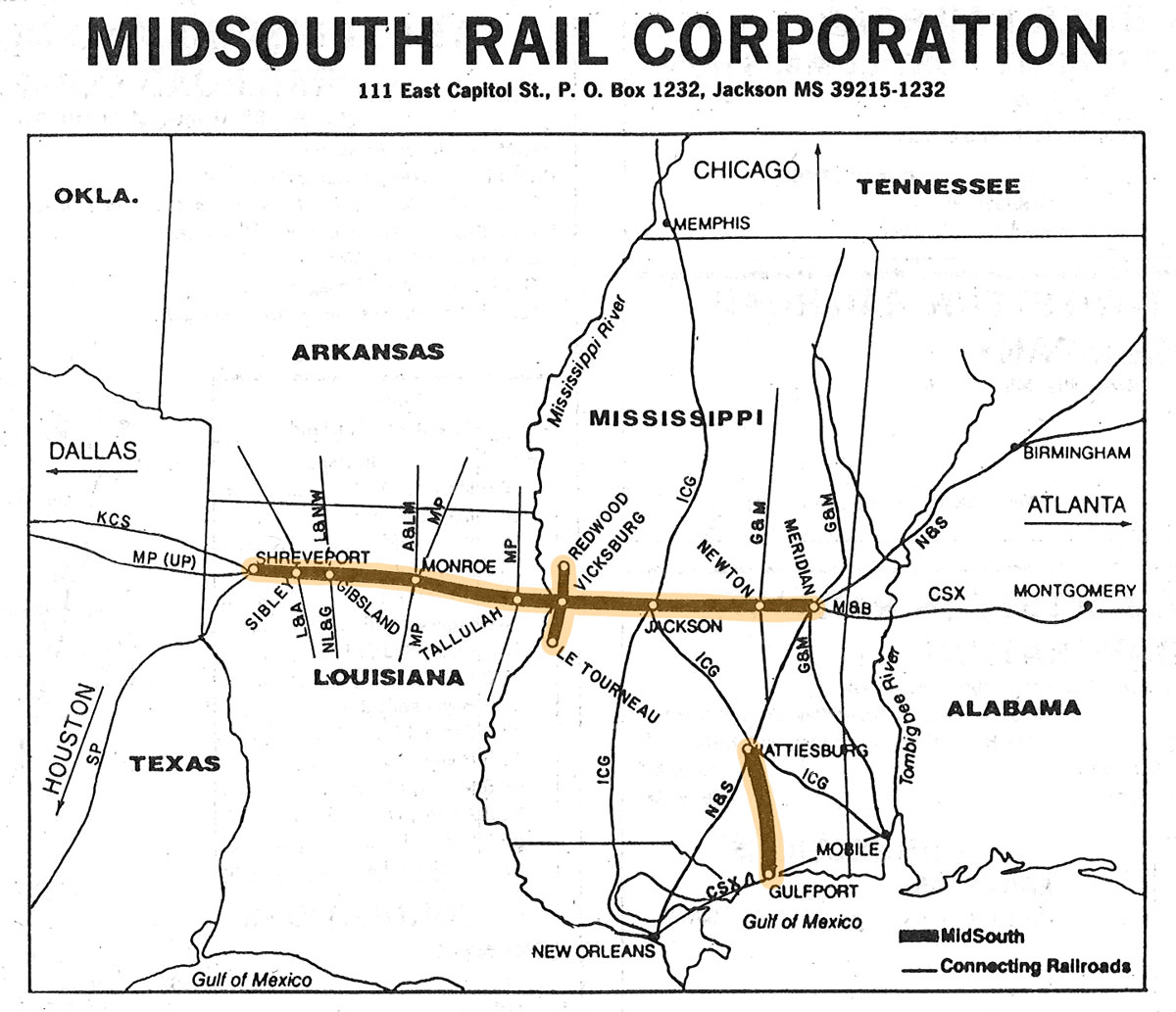

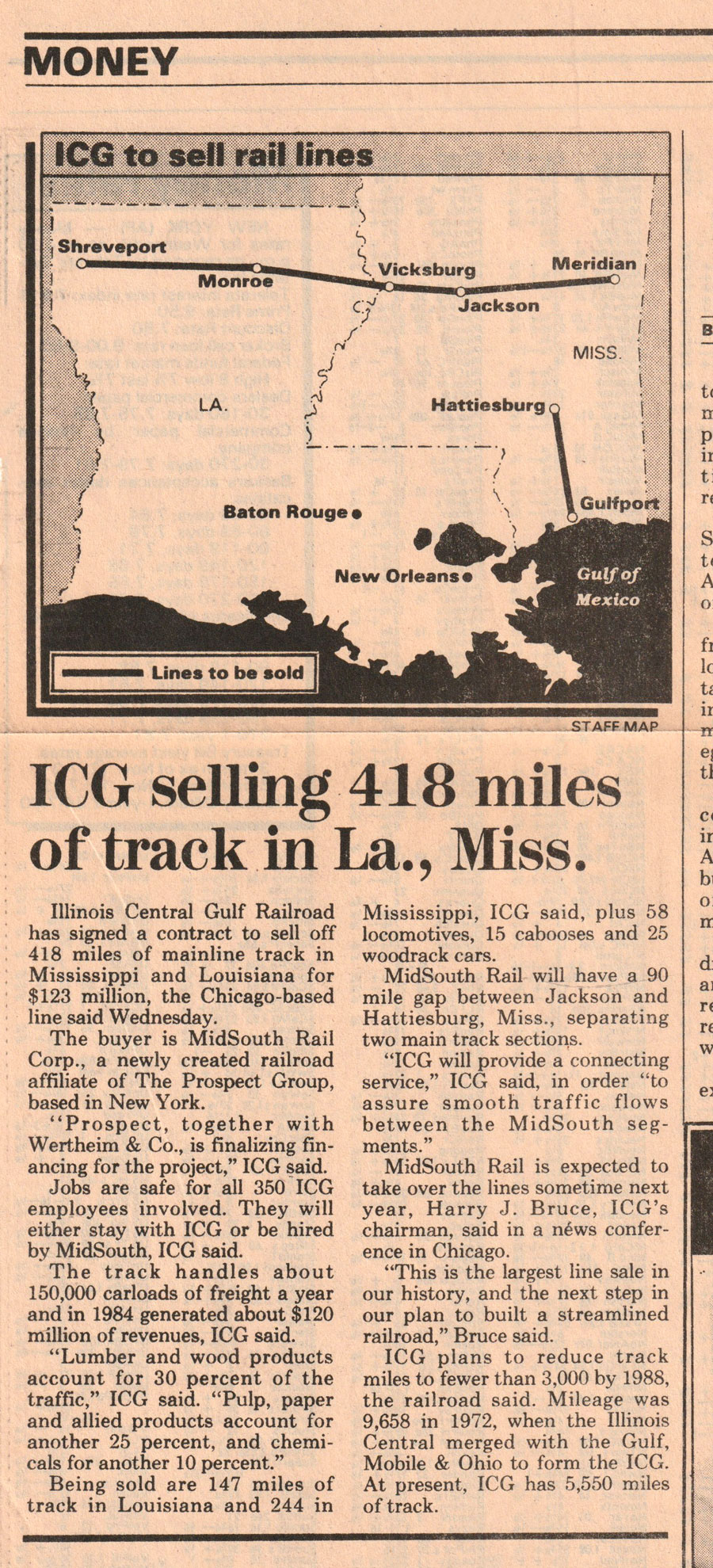

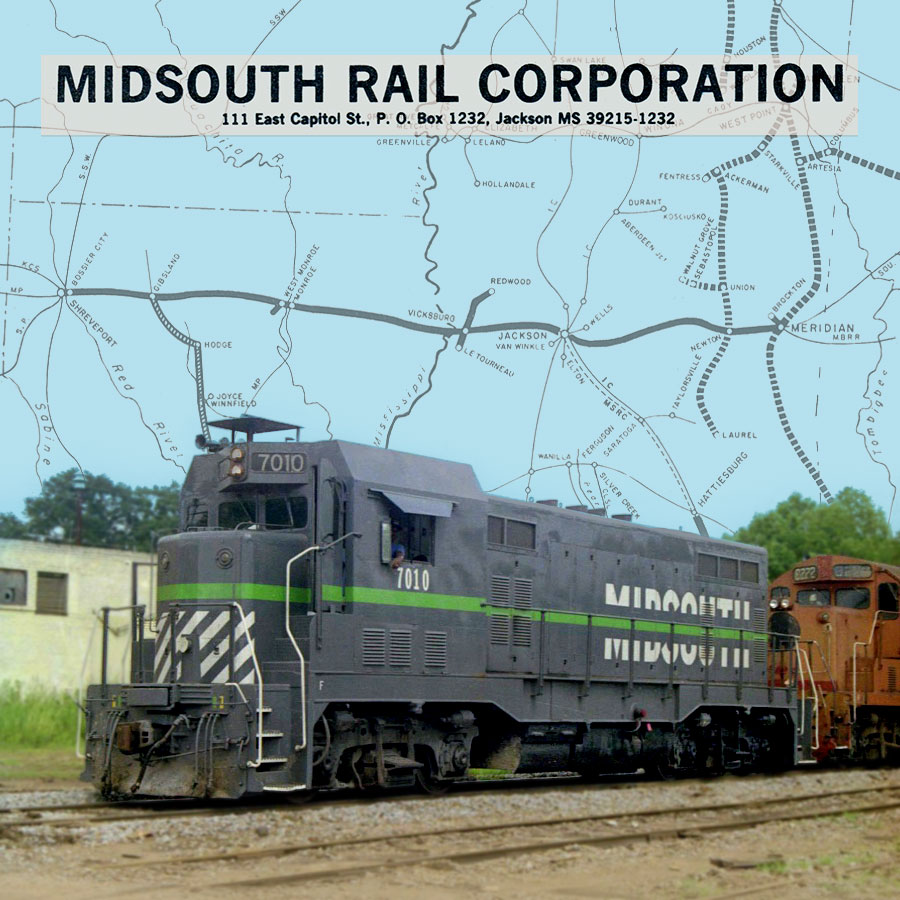

idSouth Rail was created in March 1986 to purchase 373 miles of mainline from the Illinois Central Gulf — from Meridian, Mississippi, on the eastern end to Shreveport, Louisiana, in the west. The passing of the federal Staggers Rail Act in 1980 gave large rail systems more latitude for route divestiture. As such, ICG began a series of major divestments to downsize the bloated 1972 merger of competitors Illinois Central and Gulf, Mobile & Ohio. Regional roads Chicago, Central & Pacific (1995) in the midwest and the Gulf & Mississippi (1985) in the south were the first two major ICG spinoffs; MidSouth Rail in two southern states would be the third. The Meridian-Shreveport route had a long history as an important rail corridor, but it was an ill-fitting east-west mainline in ICG's otherwise north-south national traffic pattern. Despite its oddity and lost business, the line was in decent physical shape in 1986 when compared to the rehabilitation challenges faced by regional neighbor Gulf & Mississippi. As such, the MidSouth pitch was a quick sell to investors.

idSouth Rail was created in March 1986 to purchase 373 miles of mainline from the Illinois Central Gulf — from Meridian, Mississippi, on the eastern end to Shreveport, Louisiana, in the west. The passing of the federal Staggers Rail Act in 1980 gave large rail systems more latitude for route divestiture. As such, ICG began a series of major divestments to downsize the bloated 1972 merger of competitors Illinois Central and Gulf, Mobile & Ohio. Regional roads Chicago, Central & Pacific (1995) in the midwest and the Gulf & Mississippi (1985) in the south were the first two major ICG spinoffs; MidSouth Rail in two southern states would be the third. The Meridian-Shreveport route had a long history as an important rail corridor, but it was an ill-fitting east-west mainline in ICG's otherwise north-south national traffic pattern. Despite its oddity and lost business, the line was in decent physical shape in 1986 when compared to the rehabilitation challenges faced by regional neighbor Gulf & Mississippi. As such, the MidSouth pitch was a quick sell to investors.

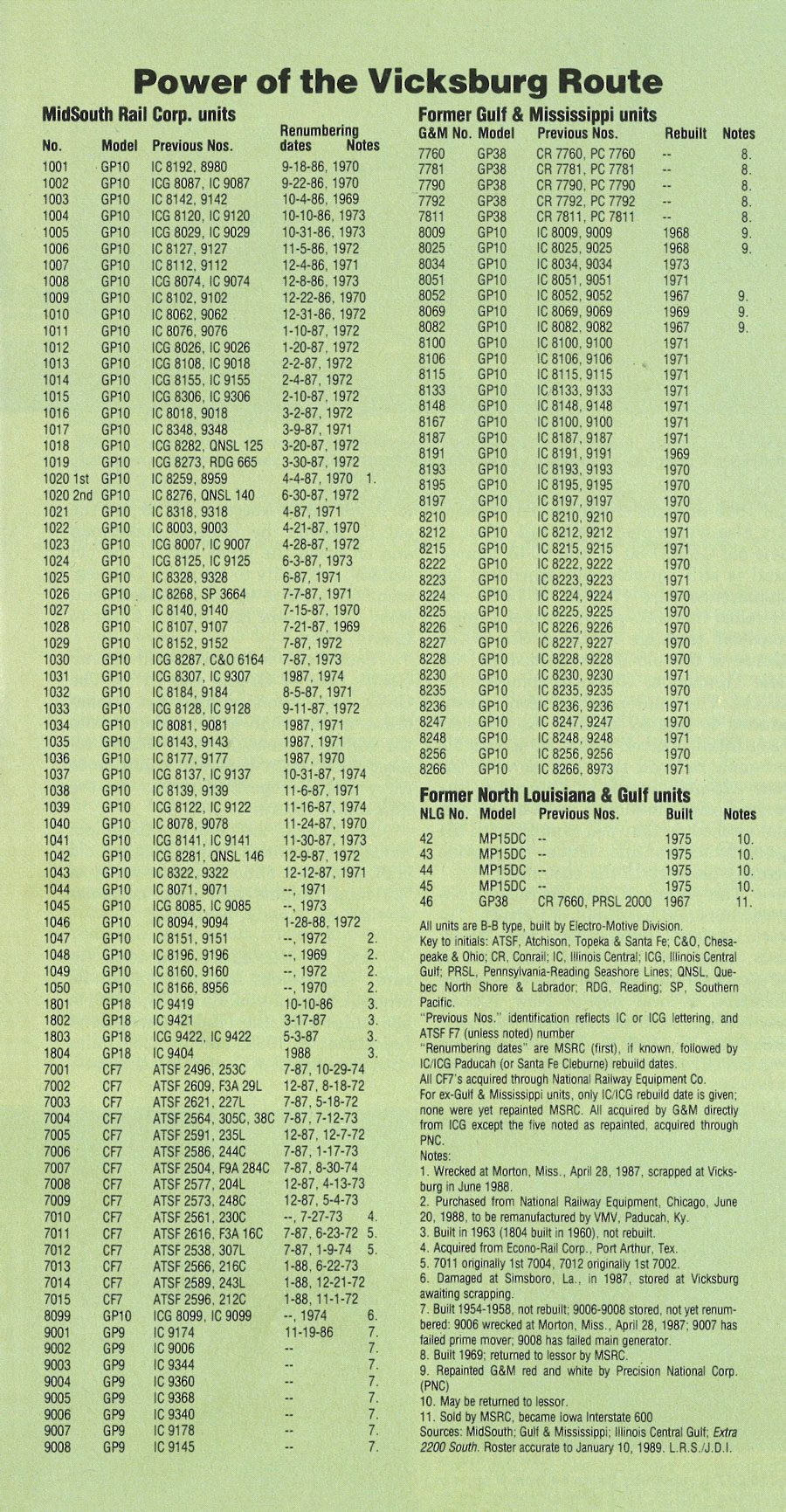

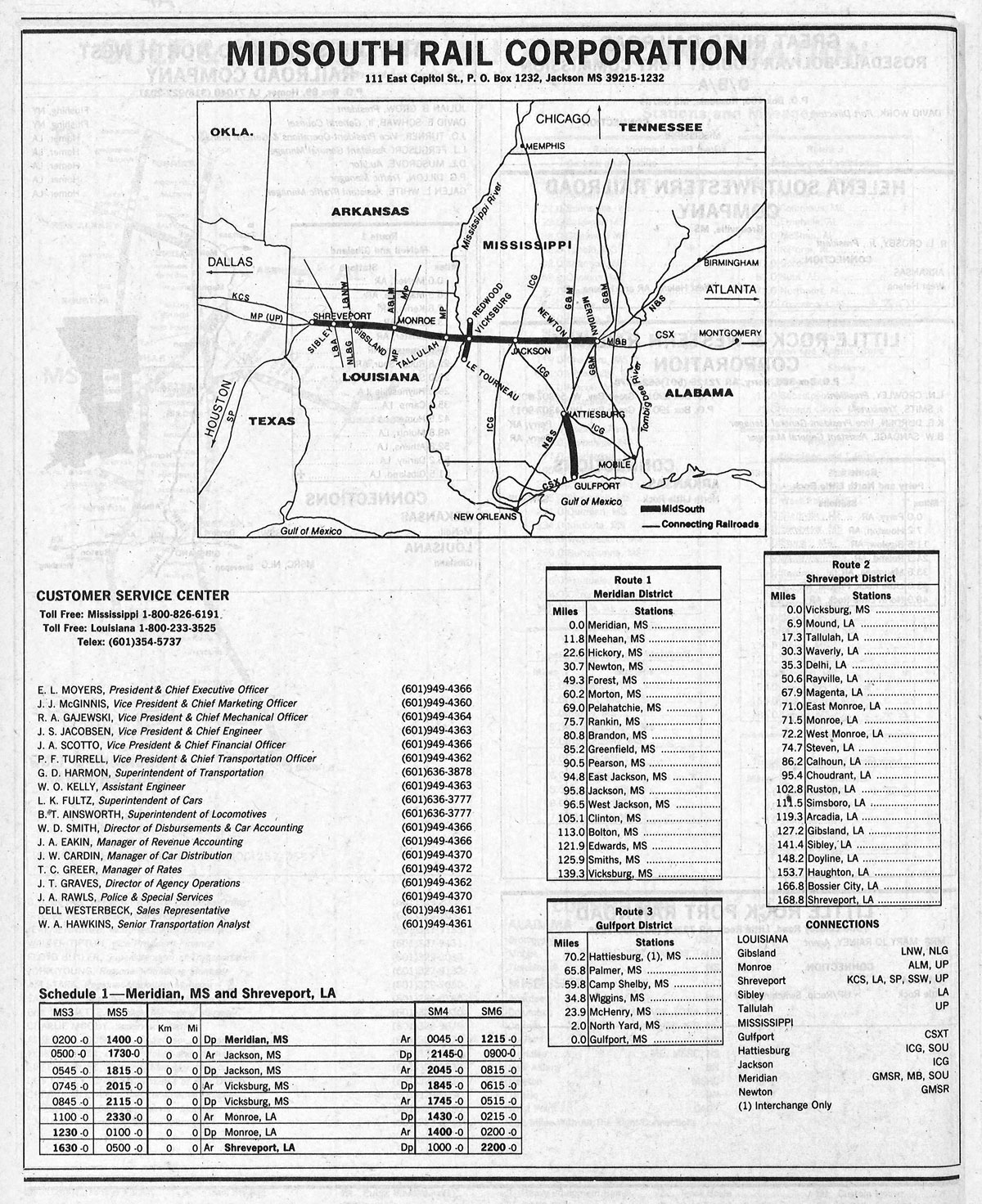

Operations began with 418 miles of railroad, 58 locomotives (all former ICG Geeps), 15 cabooses, and 25 pulpwood cars. Nearly 300 employees got the regional off the ground, 97% of which had worked for the ICG. Carloads came mostly from paper and chemical business, but pulpwood, lumber, and grain were also handled. Overhead traffic made money, too, as the regional interchanged with the (then) new Norfolk Southern at Meridian, Illinois Central Gulf in Jackson, Missouri Pacific at Monroe, the Cotton Belt at Bossier City, and both Southern Pacific and Union Pacific at Shreveport. Kansas City Southern also supplied the carrier at Shreveport: a connection that would prove prescient when KCS would purchase the successful regional less than a decade later. Between its terimini, the MidSouth also provided interchange service to 5 shortlines and regional Gulf & Mississippi. MidSouth headquarters were in Jackson; major car and locomotive shops in Vicksburg.

A short disconnected segment of rail between Hattiesburg, Mississippi, and Gulfport was also included in the formation of MidSouth: a portion of the former Gulf & Ship Island mainline from the coast up to Jackson. ICG provided haulage rights for the regional between Hattiesburg and Jackson.

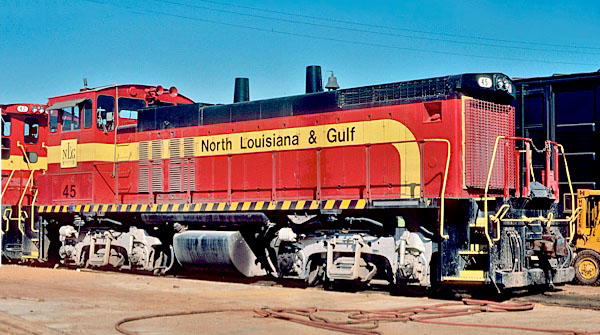

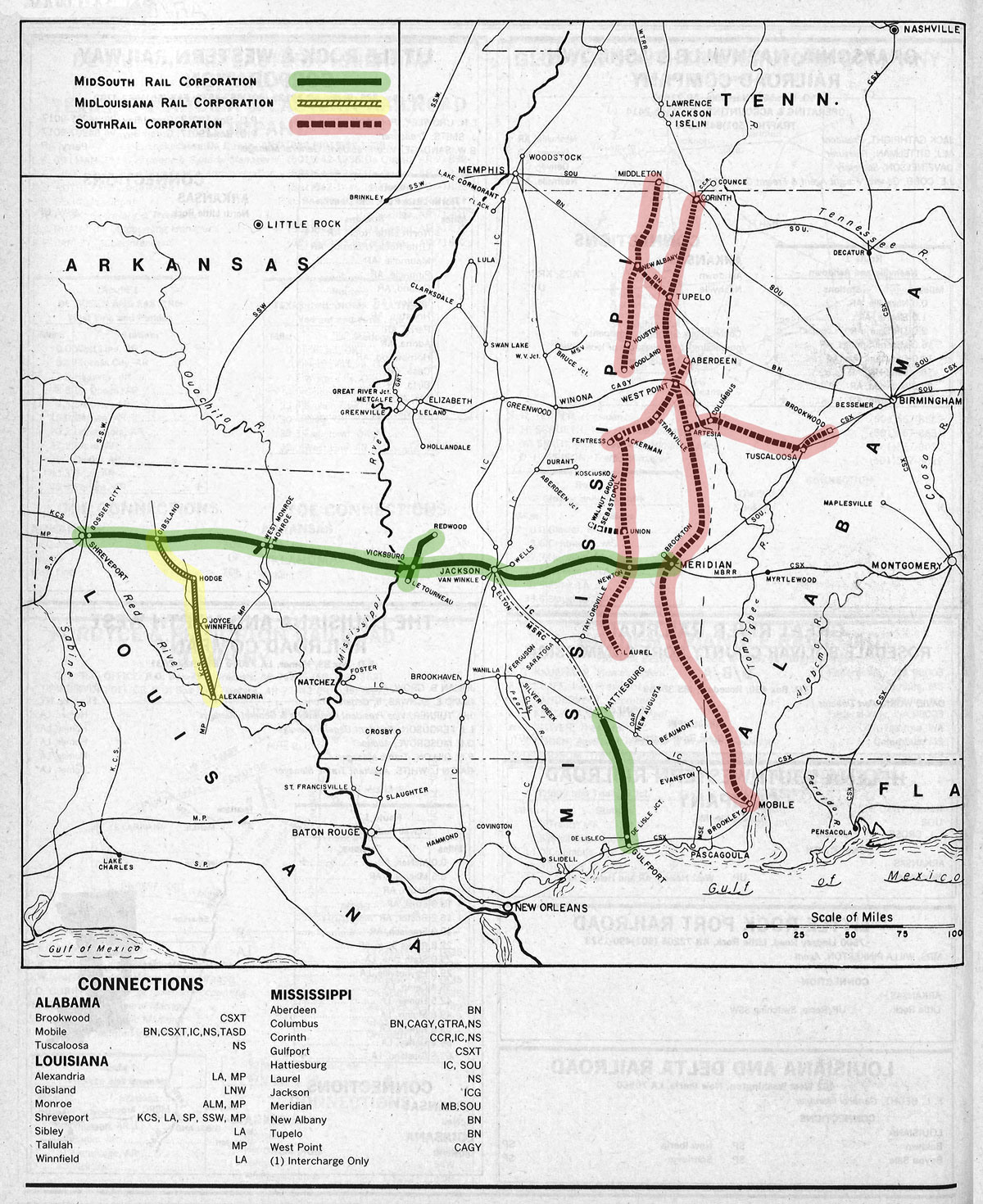

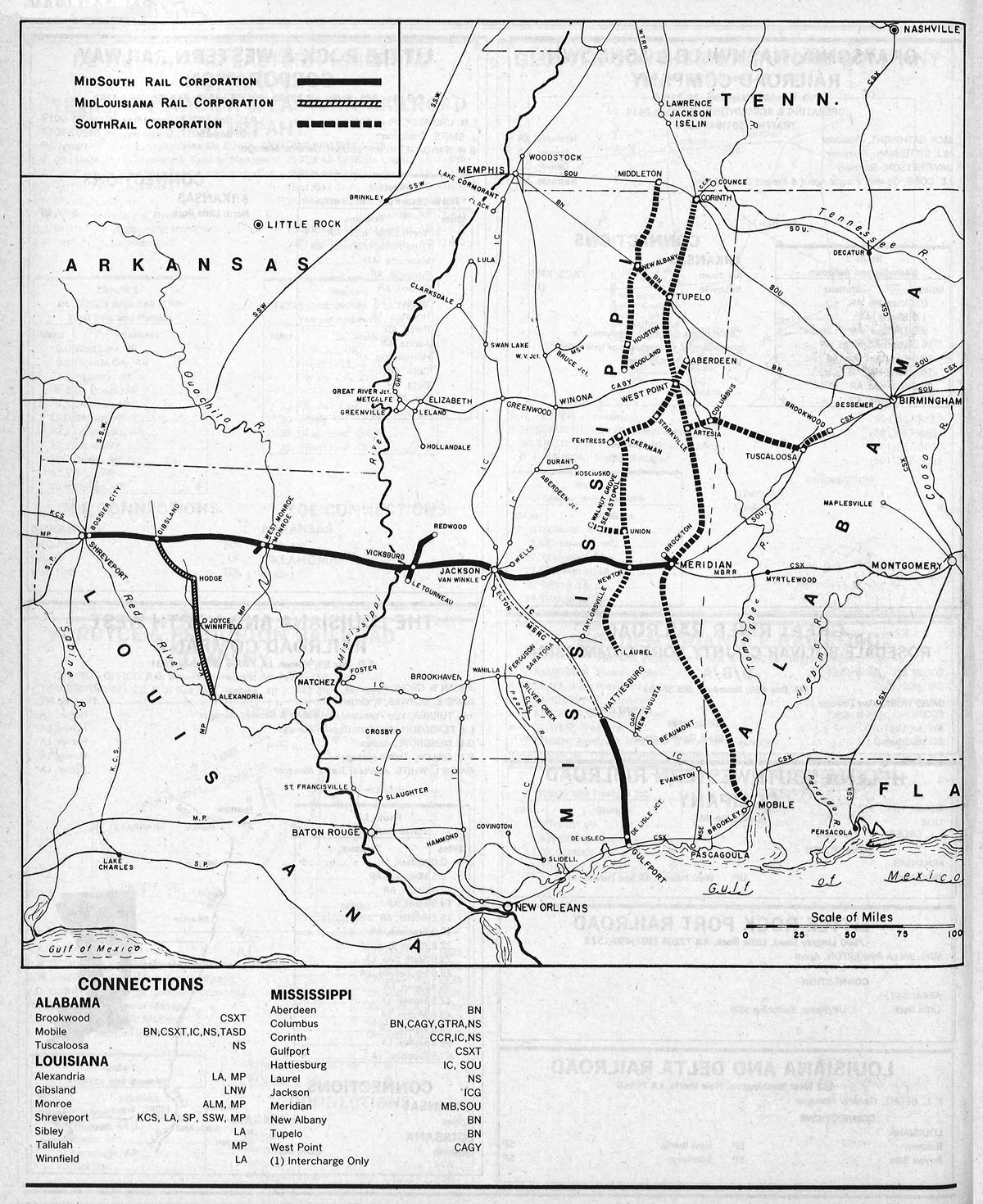

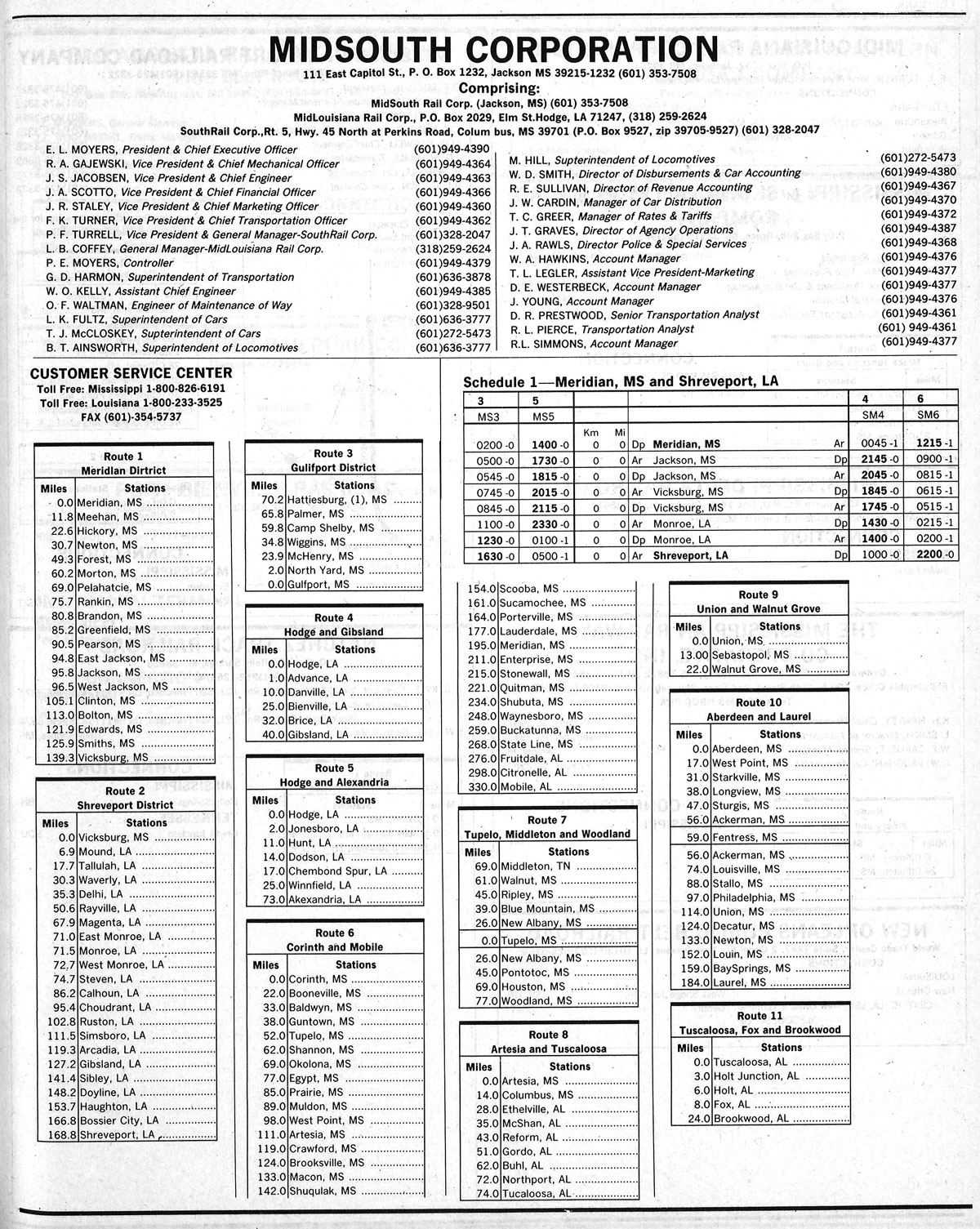

1986 Official Guide map / collection

Off to a strong start in 1986, only a year later the new MidSouth made the first of three expansions to its footprint in Mississippi and Louisiana. The shortline North Louisiana & Gulf for decades had a 40 mile line from its ICG connection at Gibsland, Louiaiana, south to a large paper mill at Hodge, and also operated a portion of former Rock Island mainline in the area. MidSouth purchased the route in 1987 and named its new subsidiary MidLouisiana Rail. A year later, MidSouth rescued its struggling regional neighbor Gulf & Mississippi from bankruptcy by incorporating its beleaguered 732 mile patchwork of former GM&O routes into a second subsidiary, SouthRail Corporation. Born of the same spinoff era as MidSouth, GMSR was plagued by purchasing poorer track conditions and faced stiff competition from Illinois Central Gulf and Burlington Northern in the region. Connections at Newton and Meridian gave MidSouth a means for incorporating GMSR traffic (mostly forest products) into its ambitious operating plan, as well as rehabilitating much of its aged infrastructure. Finally, in 1991, MidSouth purchased the 16 mile Corinth & Counce shortline in northeast Mississippi. This third subsidiary it called TennRail.

collection

1988 Official Guide map / RWH adaptations / collection

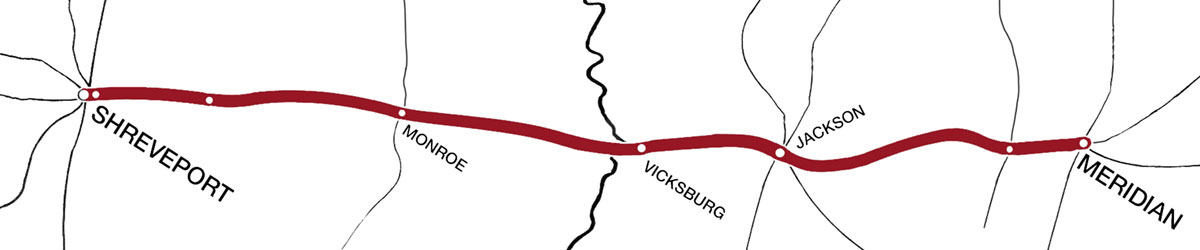

MidSouth Rail Corporation's enhancement of the Meridian-Shreveport corridor (physical plant and traffic) combined with its successful stabilization of the Gulf & Mississippi made the regional an attractive candidate for purchase by a larger system. By 1993, predecessor Illinois Central Gulf was no longer on the scene. The slimmer system had reorganized itself in the late 1980s, returning to its Illinois Central nomenclature. Ironically, the "new" IC offered to buy the successful MidSouth in 1990, but the regional declined the offer and the pursuit was dropped. Meanwhile, Kansas City Southern was also looking for expansion and in 1991 offered to purchase the MidSouth less than a decade after it was formed. The plan was approved in 1993. KCS saw untapped potential in the Merdian-Shreveport mainline, and quickly went to work adding more welded rail, signalling and technology, increased yard capacity, and numerous passing sidings in order to handle prosperous through freights and intermodal traffic between the southeast and the Dallas market. Today the route is known as the "Meridian Speedway," a joint venture between KCS and Norfolk Southern. After the buyout, nearly all of the 117 Paducah rebuilds, standard Geeps, and Cleburne CF7s rostered by MidSouth found homes in the shortline, switching, and lease power markets. Although KCS has since divested much of the former Gulf & Mississippi trackage to shortline operators or abandonment, the "Speedway" remains a major component of its national Class One system.

Meridian Speedway map / RWH

On May 1, 2006, Kansas City Southern (KCS) and Norfolk Southern (NS) closed on a Joint Venture to increase capacity and improve service on KCS’ Meridian Speedway between Meridian, Miss. and Shreveport, La., a direct rail connection moving rail traffic between the southeast and southwest U.S. The historic venture will strengthen the nation’s transportation network to handle traffic more efficiently and reliably.

The joint venture involves the contribution of KCS’ 320-mile line between Meridian and Shreveport to the joint venture company, MSLLC, and NS’ investment of $300 million in cash, substantially all of which will be used for capital improvements to increase capacity and improve transit times over the line. Upon completion, it is anticipated that 45 trains per day will traverse the line.

On May 1, 2006, Kansas City Southern (KCS) and Norfolk Southern (NS) closed on a Joint Venture to increase capacity and improve service on KCS’ Meridian Speedway between Meridian, Miss. and Shreveport, La., a direct rail connection moving rail traffic between the southeast and southwest U.S. The historic venture will strengthen the nation’s transportation network to handle traffic more efficiently and reliably.

The joint venture involves the contribution of KCS’ 320-mile line between Meridian and Shreveport to the joint venture company, MSLLC, and NS’ investment of $300 million in cash, substantially all of which will be used for capital improvements to increase capacity and improve transit times over the line. Upon completion, it is anticipated that 45 trains per day will traverse the line.

Kansas City Southern (2008)

Chunky, Ms / 1990 / JCH

Jackson, Ms / Dec 1988 / JCH

collection

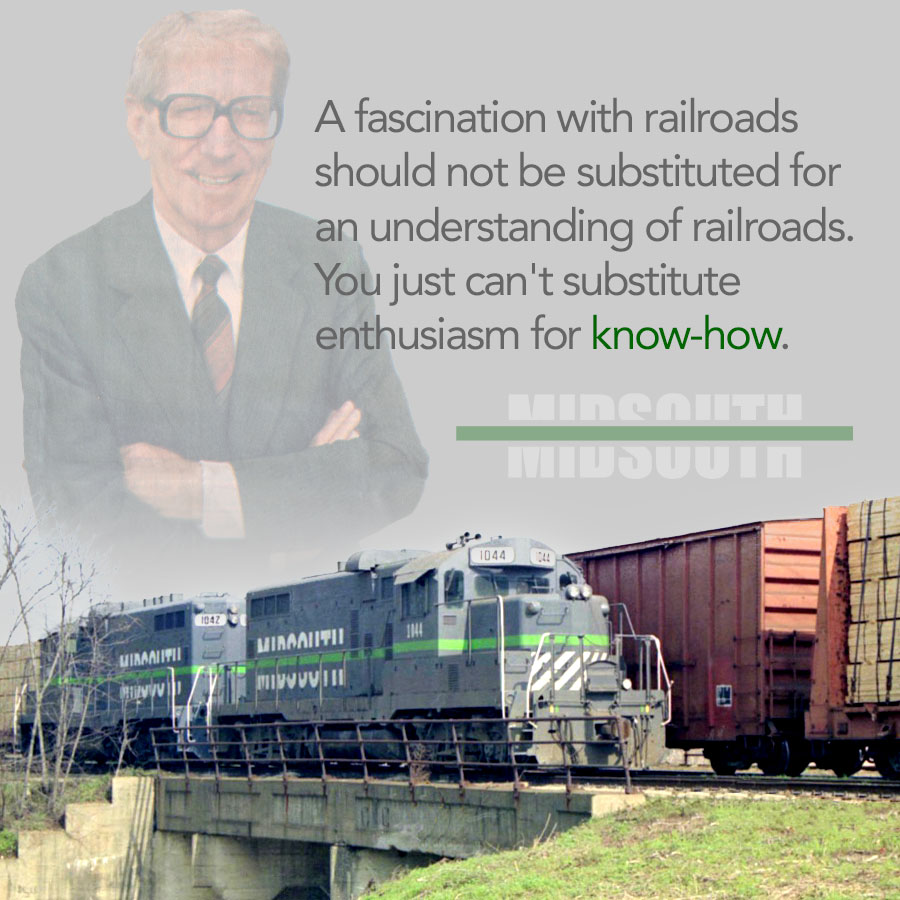

America has a great affection for railroads. Perhaps no other industry in the country has as many so-called buffs as the railroad industry. I myself have worked in the industry all my life and am, in a sense, a sort of buff. Yet a fascination with railroads should not be substituted for an understanding of railroads. These are marginal businesses that require all the skill and experience that can be marshalled in a management team. You just can't substitute enthusiasm for know-how.

America has a great affection for railroads. Perhaps no other industry in the country has as many so-called buffs as the railroad industry. I myself have worked in the industry all my life and am, in a sense, a sort of buff. Yet a fascination with railroads should not be substituted for an understanding of railroads. These are marginal businesses that require all the skill and experience that can be marshalled in a management team. You just can't substitute enthusiasm for know-how.

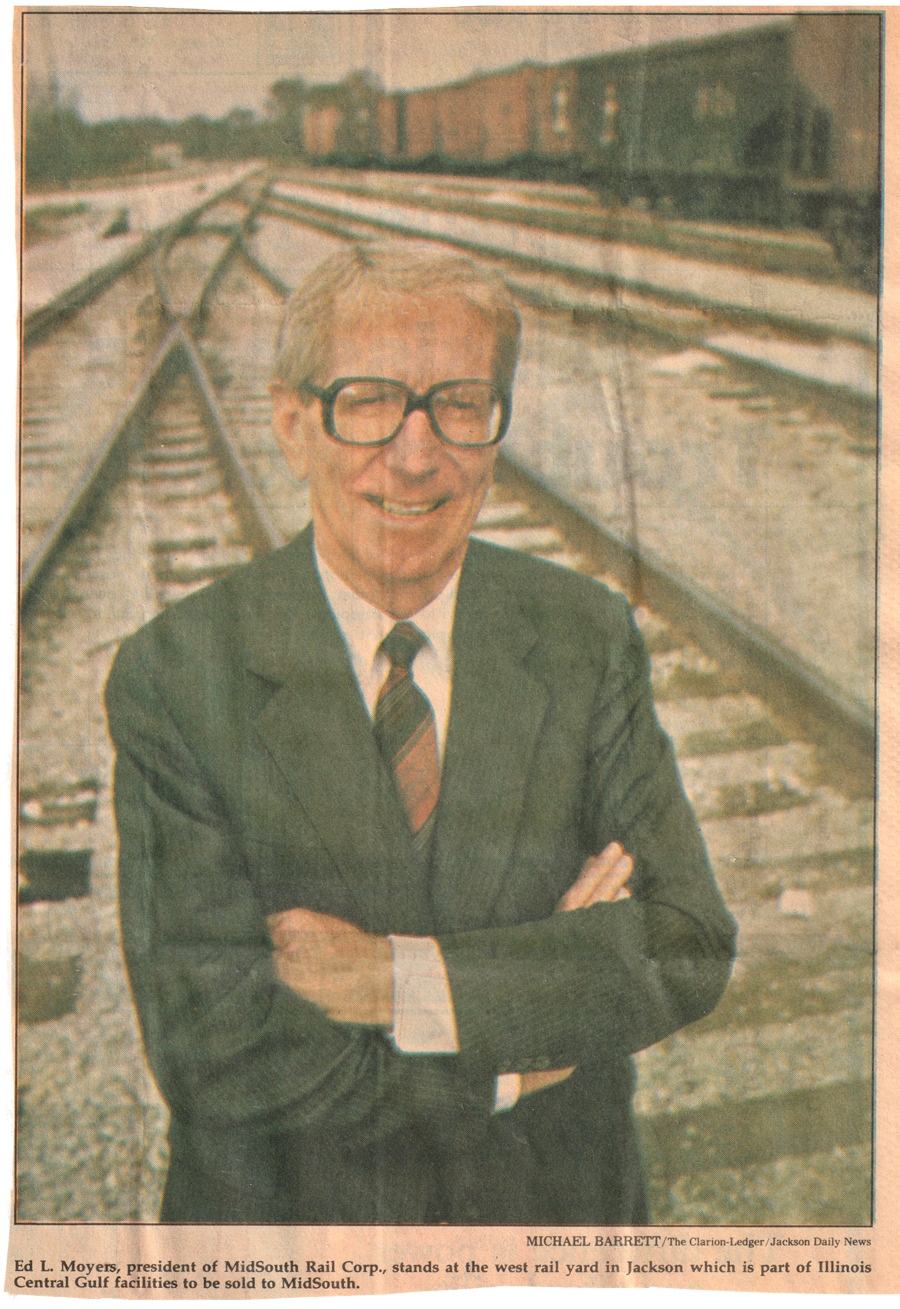

Ed Moyers / MidSouth's President and CEO / 1989

at a glance

| 1986 | 1993 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Miles operated | 474 | 1197 | |

| Locomotives | 58 | 117 | |

| Freight cars | 1571 | 4694 | |

| Reporting marks | MSRC | ||

| Headquarters | Jackson, Ms | ||

| Predecessor | Illinois Central Gulf | ||

| Affiliated roads | SouthRail, MidLouisiana Rail | ||

| Successor | Kansas City Southern | ||

collection

HawkinsRails thanks Michael Palmieri, Christopher Palmieri, and Mose Crews for sharing their MidSouth images for our scrapbooks

Vicksburg, Ms / Aug 1993 / collection

Scrapbooks

Video

HawkinsRails thanks Bishop Taylor of Louisiana Rail Productions for sharing his excellent YouTube videos

Louisiana Rail Productions

Louisiana Rail Productions

Clippings

Clippings

from New Orleans Times-Picayune newspaper - Nov 1985 / collection

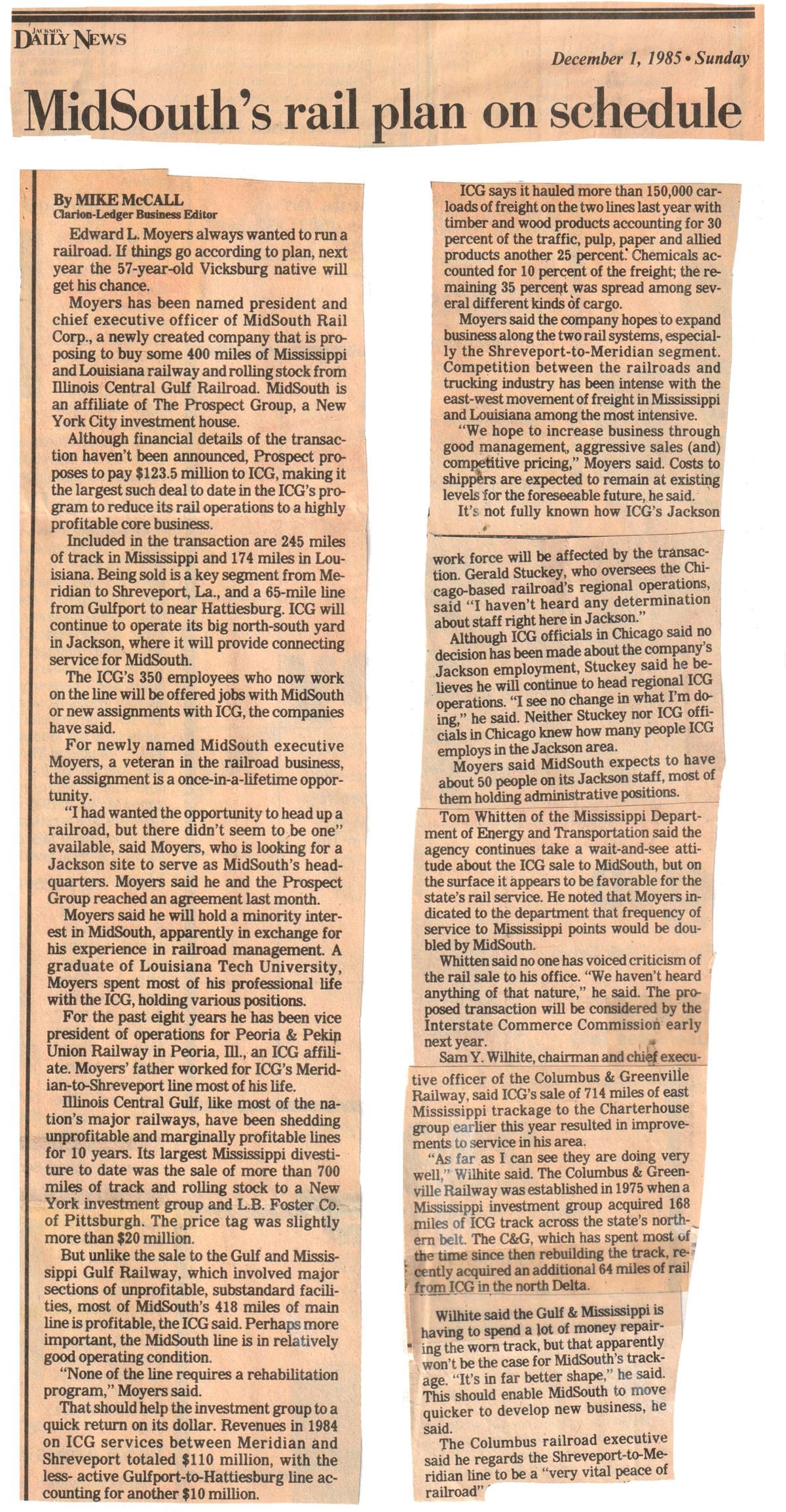

from Jackson Clarion-Ledger newspaper - Dec 1985 / collection

from Jackson Clarion-Ledger newspaper / collection

from Jackson Clarion-Ledger newspaper / collection

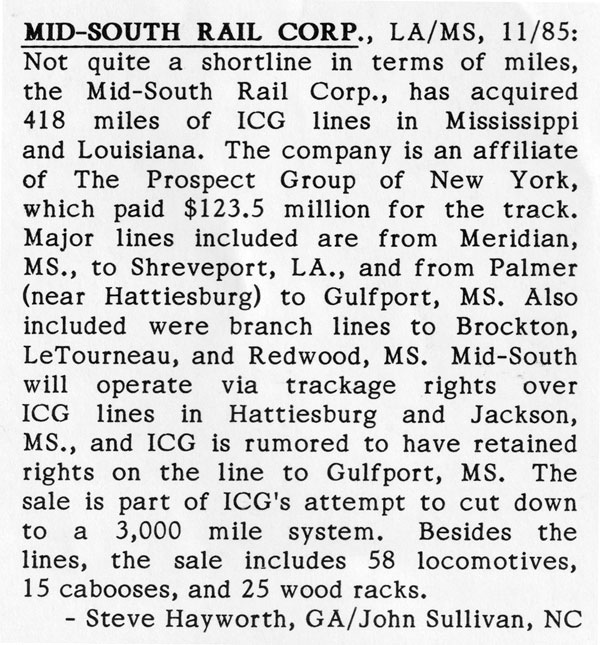

from The Short Line magazine - 1986 / collection

from GM&O Historical Society News - 1988 / collection

from Railway Age magazine - May 1986 / collection

from Railway Age magazine - May 1988 / collection

Article

Article

F. K. Plous Jr — Contributing Editor

May 1988

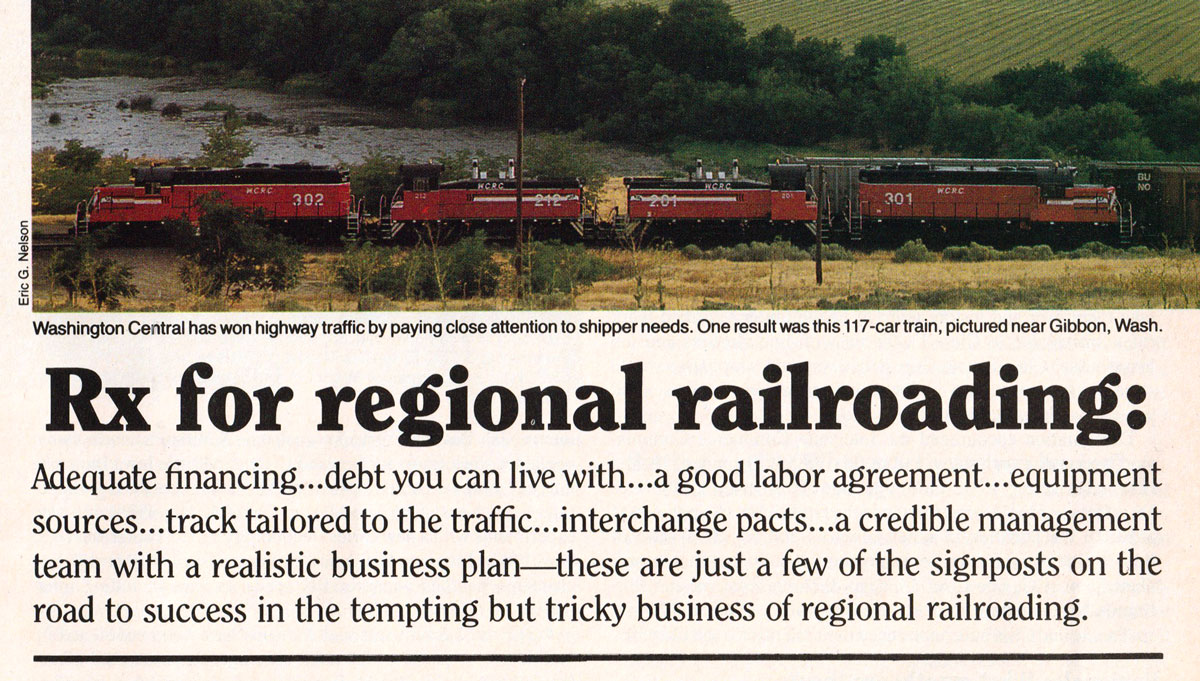

When historians of the future review the U.S. railroad industry in the second half of the 20th Century, which development is likely to excite them most? Dieselization? Ctc? Computers? Deregulation? Mega-mer-gers? Intermodalism?

Each has made undoubted contributions to railroading's long struggle to reform itself. Several properties probably owe their continued existence to one or more of those innovations.

But the industry's most productive achievement may ultimately prove to have been a long-overdue transformation in the nature of railroad ownership. As the '80s unrolled, a growing proportion of the nation's main line rail mileage was spun off from Class I carriers — historically owned by thousands of stockholders who trade their shares publicly into the hands of small syndicates, partnerships or sole proprietors managing their own companies. By the end of 1987 nearly 15,000 of the nation's 188,028 railroad route miles were listed in the closely held regional category.

But the industry's most productive achievement may ultimately prove to have been a long-overdue transformation in the nature of railroad ownership. As the '80s unrolled, a growing proportion of the nation's main line rail mileage was spun off from Class I carriers — historically owned by thousands of stockholders who trade their shares publicly into the hands of small syndicates, partnerships or sole proprietors managing their own companies. By the end of 1987 nearly 15,000 of the nation's 188,028 railroad route miles were listed in the closely held regional category.

Today the industry's regional sector is doing something that only a few years ago was believed impossible in railroading: It's becoming entrepreneurial. An aspiring businessman can buy a railroad property and start shaping it according to a personal vision. If he's got what it takes (including luck), he's got a reasonable chance of transforming his multi-million-dollar baby from a traditional American railroad into a competitive, market-driven and best of all, profitable member of the free enterprise club.

Why regionals? Why now?

According to most accounts, regionalization got its start in the wave of northeastern and midwestern railroad bankruptcies that occurred in the '70s and early '80s largely those affecting Penn Central, Rock Island, and the smaller carriers later merged into the Conrail system. As bankruptcy trustees moved to liquidate real estate and equipment, they began to receive offers from entrepreneurs seeking line segments eligible to be placed back in operation.

The way these would-be railroaders saw it, some of those light-density lines would have been economically viable all along if their Class I owners hadn't been forced by union agreements and the Railway Labor Act to operate them with five-man crews, 100-mile crew districts and other expensive relics of the steam era. Those same lines, re-opened by new managements free to staff their lines under rational work rules at costs comparable to those in other industries, could earn a profit, fix up their plants and win back some customers.

Regionalization: Phase II

That scenario succeeded in a variety of locations, setting the scene for a second phase of regionalizing in the mid-'80s. When Harry J. Bruce became chairman of the Illinois Central Gulf in 1983, he concluded that 6,000 miles of ICG's 9,500-mile system- mostly secondary main or branch lines either were losing money or were earning too little to pay for their next major overhaul. When management proposed work-rules reform to reduce costs and save the lines, the unions balked, insisting that employees on lines with light traffic had to be paid the same as those on more lucrative trackage as long as both were under the same ownership.

Historically, railroads owning such doomed lines had abandoned them. But after reviewing the success of start-up carriers operating with reformed work rules on liquidated Penn Central and Rock Island trackage, Bruce began to wonder if the classic cycle of Decline, Fall and Resurrection couldn't be telescoped a bit to eliminate the Fall. Why put shippers, employees, and regulators through the agony of abandonment or even bankruptcy before achieving successful railroading? Must a railroad die before it can live again?

Bruce's solution was simple: Identify the problem lines before they get into real trouble. Then sell them to entrepreneurs who can take them over and restore them to health under reformed work rules unavailable to Class I's. Faced with line closures and job losses under Class I ownership, Bruce wagered, employees would choose job preservation at lower pay under new owners. And service would continue uninterrupted.

Deregulation encouraged the Interstate Commerce Commission to expedite such sales, and in July 1985 ICG spun off its first regional offspring, a 732-mile collection of former Gulf, Mobile & Ohio lines in Mississippi christened the Gulf & Mississippi. G&M attracted the attention of other Class I's and set off a wave of branch-line spinoffs and entrepreneurial start-ups that hasn't abated yet. ICG, Soo Line, Chicago & North Western, and Burlington Northern have sold thousands of miles of line, and Southern Pacific and CSX have announced their intention to do likewise.

The Deal: Bankers, lawyers and bright ideas

Whatever their differences, all regionals have at least one thing in common: An entrepreneur wants to buy up and save a threatened piece of railroad and goes hunting for some lawyers and financiers to put the deal together. They're essential because creating a regional railroad is one of the most compies, duffed and challenging kinds of transactions taking place in Anericar, business today.

"The MidSouth agreements were several thousand pages long," says Mark Levin, the Washington, D.C., lawyer who structured the spinoff of Illinois Central Gulf's 403-mile Meridian (Miss.) - Shreveport (La.) line. "I have three bound volumes here in my office, each nine inches thick." Levin, who was chief legal counsel to former ICC Chairman Darius Gaskins, can tick off the contents by heart.

"The MidSouth agreements were several thousand pages long," says Mark Levin, the Washington, D.C., lawyer who structured the spinoff of Illinois Central Gulf's 403-mile Meridian (Miss.) - Shreveport (La.) line. "I have three bound volumes here in my office, each nine inches thick." Levin, who was chief legal counsel to former ICC Chairman Darius Gaskins, can tick off the contents by heart.

"Number one, you've got to have a financing agreement with the bank," he says. "You've got to have another agreement with your shareholders, partners or other backers. If you're unionized you'll have to have a labor agreement. You'll have to have an agreement with your equipment lessors. You've got to have an interchange equipment with the selling railroad and with any other railroad with which you connect. Usually there are equipment and supply agreements with the seller covering only locomotives, rolling stock or other equipment that comes with the deal. You may have an agreement to finance the purchase of locomotives. You will have to do a Uniform Commercial Code filing. There may be title-insurance problems, since you're buying a piece of real estate."

"It's going to cost you a million dollars in working capital and at least a year of pre-purchase analysis and preparation to get a regional railroad under way," says partner Norman Carlson of Arthur Andersen & Co. "In my experience, regional railroads are the most difficult of all businesses to get started."

Carlson defines the problem as one of transition: Prior to the sale, the line scheduled to become a regional had no top management of its own- only a share of the managerial time and skill of its Class I owner.

But well before Day One of the new ownership, it's got to have its own top-management team with a fresh business plan that makes sense for a line that's now an independent company. That's a tall order because regional railroading is a new industry. It has no veterans.

Getting down to work: Selling the New Company

"The big problem is that we have terrible transit times in this industry," [Tony Hannold] says. "There's also the problem of irregularity. You'll hear quotes of between four and 14 days for a shipment coming from California. The customer who hears that will tell you, 'We can cope with the delay if it has a price factor in it. But the times are so erratic. Between four and 14 days? How can we plan for that? If the shipment comes in early we'll have to pay to store it.'"

But other carriers report that the change of ownership has made it easier to get new business. MidSouth President Edward L. Moyers, whose road often is ranked as the most successful new regional, says a fresh attitude among train crews was partly responsible.

But other carriers report that the change of ownership has made it easier to get new business. MidSouth President Edward L. Moyers, whose road often is ranked as the most successful new regional, says a fresh attitude among train crews was partly responsible.

"They actually did some soliciting for us," Moyers says. "But the number-one thing they did was to convey an attitude to shippers that we wanted their business. Some shippers were just flabbergasted by the change in attitude. One grain elevator had not shipped in 11 years. Another hadn't shipped in eight years. We also had increases from almost all of the existing customers."

Other new business came from a combination of creative thinking and the 59-year-old Moyers' decades of experience — first as a summer IC track worker during college, then 20 years in a variety of IC and ICG departments, then a stint as president of the Peoria & Pekin Union Railroad.

"Working up in the Midwest with a big railroad I'd seen how small grain shippers could team up to put together a unit train to the Gulf Coast for export," he says. "I wondered, why can't we do the opposite? Let ICG or MP furnish us with a unit train and we'll disassemble it and distribute the cars to the chicken feeders down here. We've got 37 million chicks on our line, and they can really eat." Moyers says the unit-train deliveries have been a win-win proposition for everybody.

"We've been doing it for about a year now, and chicken-feed costs around here have dropped because of it," he says. "The shipper is receiving a trainload rate for 90% of the distance. It's all com, moving on one waybill. We call Archer Daniels Midland and they tell us 'three cars to this guy and two cars to this other one' and so on. They don't indicate on individual waybills which feeder is getting which cars, so we can switch them any way we want. It saves lot of time and money. Afterwards we just call them back and tell them which cars went to which consignee. We think this is unique. As a result of it our business is way up."

Also encouraging is where the traffic is coming from. "Any new traffic we've taken has come from trucks," Moyers says. "We haven't got any railroad paralleling us."

excerpts from article by F. K. Plous Jr / Railway Age / May 1988

from TRAINS magazine - Apr 1989 / collection

from TRAINS magazine - Apr 1989 / collection

collection

Article

Article

MIDSOUTH RAILROAD CORPORATION

adapted from Rebirth of the Vicksburg Route by Louis Saillard — TRAINS Magazine — April 1989

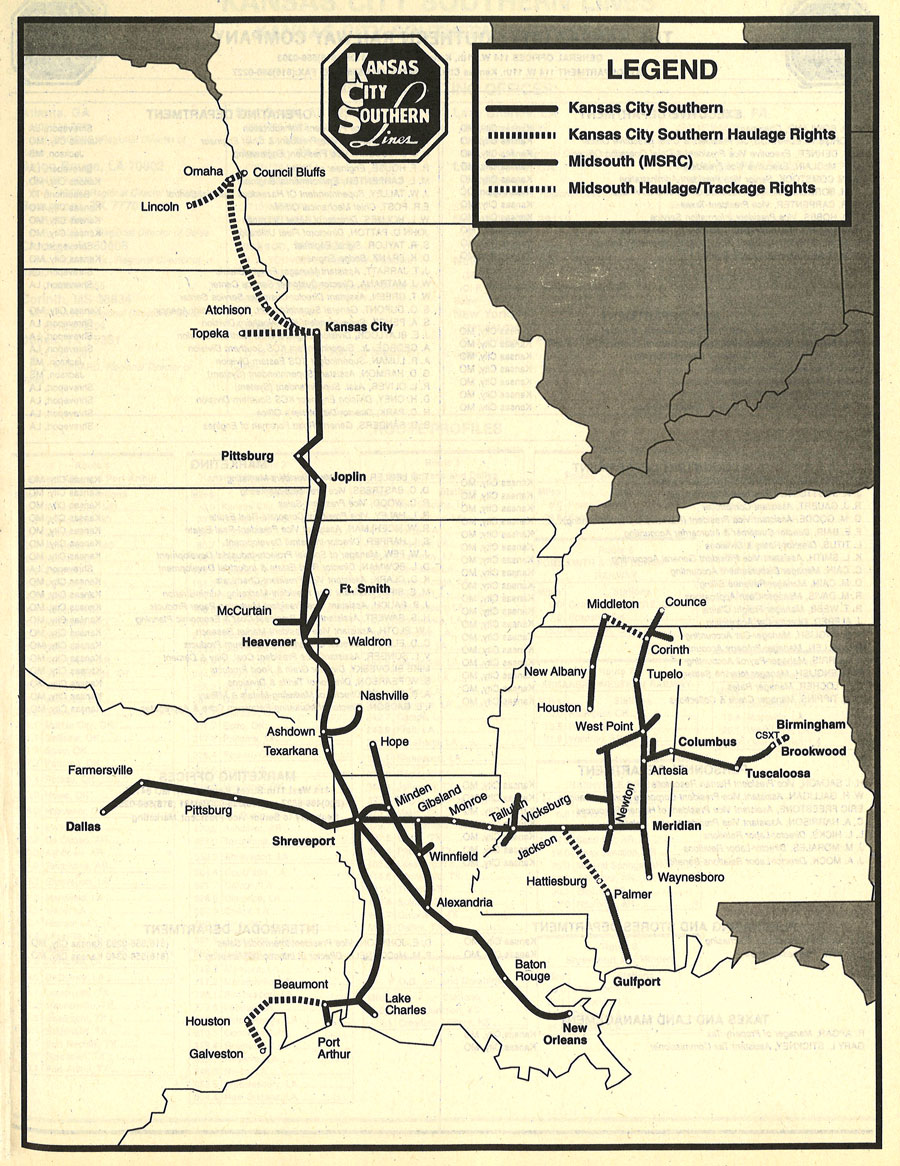

The largest acquisition of any other railroad since acquiring the L&A in 1939, was that of the 1,212 mile long MidSouth Railroad. MidSouth connects with the KCS at Shreveport, Louisiana, and heads due east across the state of Louisiana, to Vicksburg, Mississippi, then easterly still through Jackson and on to Meridian, Mississippi. The main line turns north to Artesia, Mississippi, then east again to Tuscaloosa, Alabama, and finally (via trackage rights) into Birmingham, Alabama; with other branches reaching into Counce, Tennessee, and down to Gulfport, Mississippi. This now gives KCS (traditionally a north-south railroad) a new east-west route between Dallas Texas, and Birmingham, Alabama.

The largest acquisition of any other railroad since acquiring the L&A in 1939, was that of the 1,212 mile long MidSouth Railroad. MidSouth connects with the KCS at Shreveport, Louisiana, and heads due east across the state of Louisiana, to Vicksburg, Mississippi, then easterly still through Jackson and on to Meridian, Mississippi. The main line turns north to Artesia, Mississippi, then east again to Tuscaloosa, Alabama, and finally (via trackage rights) into Birmingham, Alabama; with other branches reaching into Counce, Tennessee, and down to Gulfport, Mississippi. This now gives KCS (traditionally a north-south railroad) a new east-west route between Dallas Texas, and Birmingham, Alabama.

KCS's latest acquisition, MidSouth Rail Corporation (MSRC), has historic roots some 50 years older than KCS's own origin. The Clinton & Vicksburg Railroad (later the Vicksburg & Jackson) was incorporated in 1833 and pushed eastward by 1836. A new steam locomotive called the COMMERCIAL was put in regular service May 15, 1838.

By 1810, the Vicksburg & Jackson was connecting its namesake cities, and in conjunction with work done by other companies, trains were running across the state of Mississippi from Vicksburg to Meridian, 140 miles, by June 3, 1861. Across the river from Vicksburg, at Delta Point, Louisiana, the Vicksburg, Shreveport & Texas was in the last stages of connecting the Mississippi River with Ouachita River at Monroe, Louisiana. Having enhanced the commercial importance of their city above the Great River, the people of Vicksburg then watched while much of their labor and investment was destroyed by the Civil War (1861 to 1865) that followed. The city's strategic, and easily defended, location resulted in a devastating siege (May 19 to July 4, 1863). In Mississippi, military action west of Meridian in 1864 destroyed 51 bridges and removed four miles of track and by 1865, the cross state line was exhausted both physically and financially.

Post Civil War progress, at first frustrating, ultimately became encouraging. The railroads on both sides of the river at Vicksburg were reorganized. In 1870, construction in Alabama gave Vicksburg an allrail link to the East for the first time. To the west, the VS&T, renamed the North Louisiana & Texas, was rebuilt and resumed through service on July 1, 1870. Times were still desperate in the Reconstruction South though, and the NL&T soon collapsed financially. In 1879, it emerged from bankruptcy with a new name that would last: Vicksburg, Shreveport & Pacific. On August 1, 1884, the VS&P was completed to Shreveport, and a connection with the Texas & Pacific, brightened the future of Vicksburg.

The tracks east of Vicksburg in 1870 were known as the Southern Railroad of Mississippi (no connection to the later Southern Railway), later reorganized as the Vicksburg & Meridian, but like the NL&T across the river, failed to prosper. On February 1, 1889, the Vicksburg & Meridian was sold under foreclosure to the owners of the Queen & Crescent System and organized March 18th as the Alabama & Vicksburg. The Q&C had already purchased control of the VS&P in 1881, so now controlled a "Y"shaped system centered in Meridian, with legs extending to Cincinnati, New Orleans, and Shreveport. On October 27, 1885, inclines had been completed at Vicksburg on the river, and through freight and passenger service across the river had begun via rail transfer steamer.

The tracks from Meridian to Shreveport remained part of the Q&C System from 1889 to 1926 and prospered. With the financial backing needed to properly operate the line for the first time in its history, the combined A&VVS&P was improved and upgraded.

On October 24, 1892, the northsouth Louisville, New Orleans & Texas became part of the Yazoo & Mississippi Valley Railroad, an Illinois Central subsidiary, and Vicksburg remained a busy railroad town into the 20th Century. Even in the 1920's six daily passenger trains served the city in each direction on both the eastwest and the old LNO&T lines. After World War I, the Meridian-Shreveport main was promoted as "The Vicksburg Route."

On October 24, 1892, the northsouth Louisville, New Orleans & Texas became part of the Yazoo & Mississippi Valley Railroad, an Illinois Central subsidiary, and Vicksburg remained a busy railroad town into the 20th Century. Even in the 1920's six daily passenger trains served the city in each direction on both the eastwest and the old LNO&T lines. After World War I, the Meridian-Shreveport main was promoted as "The Vicksburg Route."

The five rail lines which made up the old Queen & Crescent System were eventually dispersed to other railroads. In 1926 the A&V and VS&P were, like the LNO&T, leased to Illinois Central's Y&MV (the "Yazoo"). The IC apparently saw promise in the line, because the initial lease period was 357 years, with a privilege of renewal for 999 years more!

Shortly thereafter, Vicksburg's rail transportation status was enhanced with completion on April 28, 1930, of a bridge across the Mississippi River by the citizens of Warren County, Mississippi, for both highway and rail traffic. This allowed the elimination of the steam transfer boats. The hazardous bridge was bypassed on October 17, 1977, when the Interstate 20 bridge, built 330 feet downstream from the old structure, was opened. The old bridge remains open to local highway traffic.

Shortly thereafter, Vicksburg's rail transportation status was enhanced with completion on April 28, 1930, of a bridge across the Mississippi River by the citizens of Warren County, Mississippi, for both highway and rail traffic. This allowed the elimination of the steam transfer boats. The hazardous bridge was bypassed on October 17, 1977, when the Interstate 20 bridge, built 330 feet downstream from the old structure, was opened. The old bridge remains open to local highway traffic.

With the absorption of the A&V and VS&P, the Illinois Central ruled supreme in the rail system of Vicksburg, as well as in much of Mississippi. As an example of its passenger service, information provided from an April 1953 issue of THE OFFICIAL RAILWAY GUIDE, Illinois Central ran daily Train No. 205, westbound Meridian to Shreveport, called "Southwestern Limited"; Train No. 226, eastbound, Shreveport to Meridian, called "Northeastern Limited". Passenger service on the Vicksburg Route continued until 1968. IC became Illinois Central Gulf with the 1972 merger of the Magnolia State's other major railroad, the Gulf, Mobile & Ohio. A portion of the northsouth MidSouth line through Meridian, acquired by KCS, was formerly Gulf, Mobile & Ohio. Also noted from the April 1953 issue of THE OFFICIAL RAILWAY GUIDE, GM&O ran trains between St. Louis. Missouri, and Mobile, Alabama, via Meridian, northbound Train No. 16 and southbound Train No. 16. called "Gulf Coast Rebel".

With the absorption of the A&V and VS&P, the Illinois Central ruled supreme in the rail system of Vicksburg, as well as in much of Mississippi. As an example of its passenger service, information provided from an April 1953 issue of THE OFFICIAL RAILWAY GUIDE, Illinois Central ran daily Train No. 205, westbound Meridian to Shreveport, called "Southwestern Limited"; Train No. 226, eastbound, Shreveport to Meridian, called "Northeastern Limited". Passenger service on the Vicksburg Route continued until 1968. IC became Illinois Central Gulf with the 1972 merger of the Magnolia State's other major railroad, the Gulf, Mobile & Ohio. A portion of the northsouth MidSouth line through Meridian, acquired by KCS, was formerly Gulf, Mobile & Ohio. Also noted from the April 1953 issue of THE OFFICIAL RAILWAY GUIDE, GM&O ran trains between St. Louis. Missouri, and Mobile, Alabama, via Meridian, northbound Train No. 16 and southbound Train No. 16. called "Gulf Coast Rebel".

As the 1970's waned, however, the ICG began the piecemeal abandonment and sale of the old LNO&T secondary main. By 1985, ICG had several large spin-off sales pending. On March 31, 1986. the MidSouth Rail Corporation was formed and purchased the Shreveport-Meridian main line and other branches from ICG, including a disconnected line between Hattiesburg and Gulfport,Mississippi. MidSouth's first day of operation was April 1, 1986. Approved by the Interstate Commerce Commission June 4 1993, the merger and first day of consolidated operation with the Kansas City Southern Railway Company took place on January 11, 1994. With the merger, came Business Car PROSPECTOR, repainted and renamed for KCS's founder, ARTHUR E. STILWELL, in 1995.

As the 1970's waned, however, the ICG began the piecemeal abandonment and sale of the old LNO&T secondary main. By 1985, ICG had several large spin-off sales pending. On March 31, 1986. the MidSouth Rail Corporation was formed and purchased the Shreveport-Meridian main line and other branches from ICG, including a disconnected line between Hattiesburg and Gulfport,Mississippi. MidSouth's first day of operation was April 1, 1986. Approved by the Interstate Commerce Commission June 4 1993, the merger and first day of consolidated operation with the Kansas City Southern Railway Company took place on January 11, 1994. With the merger, came Business Car PROSPECTOR, repainted and renamed for KCS's founder, ARTHUR E. STILWELL, in 1995.

Looking toward the year 2002, KCS still maintains the same vision just as Arthur Stilwell had intended: THE SHORTEST ROUTE FROM KANSAS CITY TO SALT WATER: The Kansas City Southern Railway Company!

Publications

1986 Official Guide ad / collection

1988 Official Guide ad / collection

1994 – Acquisition of the MidSouth Rail Corporation extends KCSR’s service territory to Meridian, Mississippi; Counce, Tennessee; and Tuscaloosa and Birmingham, Alabama, with trackage rights into Gulfport, Mississippi. The acquisition also allows KCSR to interchange with Norfolk Southern and CSX. The line from Dallas, Texas, to Meridian becomes the Meridian Speedway, considered the premiere rail corridor between the southeast and southwest U.S.

1994 Official Guide ad / collection

Lagniappe

Mr. Moyer's Methodology

image and artwork RWH

Meridian Showers

Meridian, Ms / Jan 1989 / RWH

The Frog and Her Prince

Ginsland, La / Jul 1993 / RWH

Superintendent of Locomotives

Jul 1989 / image and artwork RWH

Safe and On Time

Gibsland, La / Jul 1993 / RWH

Summer Shuffles

image and artwork RWH

Back Out to the Main

Simsboro, La / Jul 1993 / RWH

Homecoming Sunday

Gibsland, La / Jul 1993 / RWH

Caught 'Em Comin' and Goin'

Gibsland, La / Jul 1993 / RWH

The Daily Dance Card

Gibsland, La / Jul 1993 / RWH

Ten Cars to the Couple

Gibsland, La / Jul 1993 / RWH

"As she glides along the woodlands"

Bienville, La / Jul 1993 / RWH

Twists and Turns

Jul 1993 / RWH

Louisville Sluggers

Louisville, Ms / Jul 1989 / JCH

The Way Past Wiggins

Wiggins, Ms / Jul 1989 / JCH

Supporting Cast Members

Arcadia, La / Jul 1993 / image and artwork RWH

Snapshots

Snapshots

Vicksburg, Ms / Jun 2020 / John Hawkins III

Gulfport, Ms / Apr 2022 / RWH

Links / Sources

- Wikipedia article for MidSouth Rail Corp

- Kansas City Southern Historical Society MidSouth summary

- Railroad Picture Archives MidSouth Rail roster

- Mississippi Rails MidSouth page

- Don's Rail Photos MidSouth page

- J. Parker Lamb's An East-West Railway through the Mid-South at Meridian Speedway

Operations began with 418 miles of railroad, 58 locomotives (all former ICG Geeps), 15 cabooses, and 25 pulpwood cars. Nearly 300 employees got the regional off the ground, 97% of which had worked for the ICG. Carloads came mostly from paper and chemical business, but pulpwood, lumber, and grain were also handled. Overhead traffic made money, too, as the regional interchanged with the (then) new

Operations began with 418 miles of railroad, 58 locomotives (all former ICG Geeps), 15 cabooses, and 25 pulpwood cars. Nearly 300 employees got the regional off the ground, 97% of which had worked for the ICG. Carloads came mostly from paper and chemical business, but pulpwood, lumber, and grain were also handled. Overhead traffic made money, too, as the regional interchanged with the (then) new  MidSouth Rail Corporation's enhancement of the Meridian-Shreveport corridor (physical plant and traffic) combined with its successful stabilization of the Gulf & Mississippi made the regional an attractive candidate for purchase by a larger system. By 1993, predecessor Illinois Central Gulf was no longer on the scene. The slimmer system had reorganized itself in the late 1980s, returning to its Illinois Central nomenclature. Ironically, the "new" IC offered to buy the successful MidSouth in 1990, but the regional declined the offer and the pursuit was dropped. Meanwhile, Kansas City Southern was also looking for expansion and in 1991 offered to purchase the MidSouth less than a decade after it was formed. The plan was approved in 1993. KCS saw untapped potential in the Merdian-Shreveport mainline, and quickly went to work adding more welded rail, signalling and technology, increased yard capacity, and numerous passing sidings in order to handle prosperous through freights and intermodal traffic between the southeast and the Dallas market. Today the route is known as the "Meridian Speedway," a joint venture between KCS and Norfolk Southern. After the buyout, nearly all of the 117 Paducah rebuilds, standard Geeps, and Cleburne CF7s rostered by MidSouth found homes in the shortline, switching, and lease power markets. Although KCS has since divested much of the former Gulf & Mississippi trackage to shortline operators or abandonment, the "Speedway" remains a major component of its national Class One system.

MidSouth Rail Corporation's enhancement of the Meridian-Shreveport corridor (physical plant and traffic) combined with its successful stabilization of the Gulf & Mississippi made the regional an attractive candidate for purchase by a larger system. By 1993, predecessor Illinois Central Gulf was no longer on the scene. The slimmer system had reorganized itself in the late 1980s, returning to its Illinois Central nomenclature. Ironically, the "new" IC offered to buy the successful MidSouth in 1990, but the regional declined the offer and the pursuit was dropped. Meanwhile, Kansas City Southern was also looking for expansion and in 1991 offered to purchase the MidSouth less than a decade after it was formed. The plan was approved in 1993. KCS saw untapped potential in the Merdian-Shreveport mainline, and quickly went to work adding more welded rail, signalling and technology, increased yard capacity, and numerous passing sidings in order to handle prosperous through freights and intermodal traffic between the southeast and the Dallas market. Today the route is known as the "Meridian Speedway," a joint venture between KCS and Norfolk Southern. After the buyout, nearly all of the 117 Paducah rebuilds, standard Geeps, and Cleburne CF7s rostered by MidSouth found homes in the shortline, switching, and lease power markets. Although KCS has since divested much of the former Gulf & Mississippi trackage to shortline operators or abandonment, the "Speedway" remains a major component of its national Class One system.