|

Amtrak Great Stations New York, New York |

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

New York Penn Station

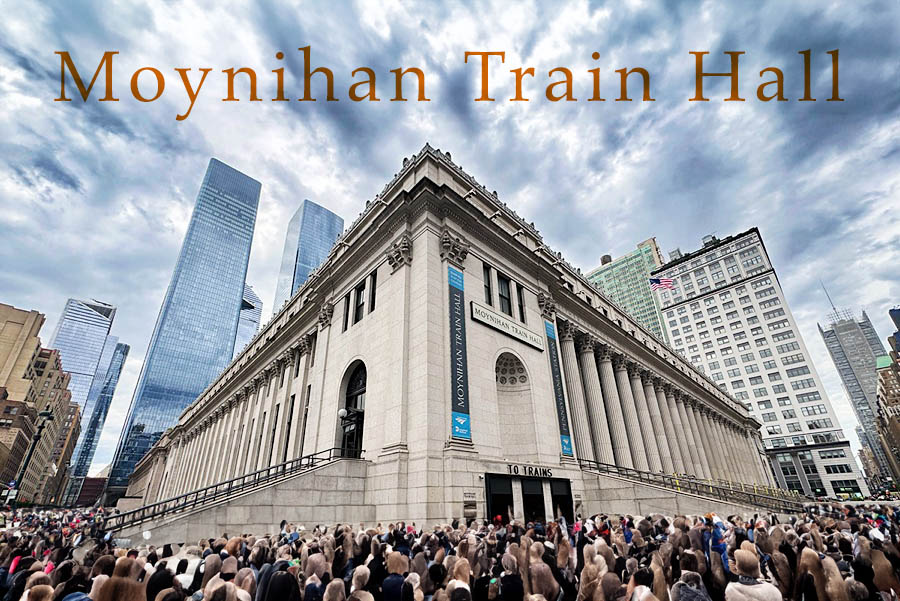

mtrak, in partnership with Empire State Development (State of New York), expanded its footprint in New York City with the opening of the Moynihan Train Hall on January 1, 2021. The Moynihan Train Hall is located inside the historic James A. Farley Post Office building, which occupies two full city blocks between W. 31st and W. 33rd Streets and 8th and 9th Avenues in the Midtown West area of Manhattan. Directly across 8th Ave. to the east is New York Penn Station, while the Hudson Yards complex is about one block west.

mtrak, in partnership with Empire State Development (State of New York), expanded its footprint in New York City with the opening of the Moynihan Train Hall on January 1, 2021. The Moynihan Train Hall is located inside the historic James A. Farley Post Office building, which occupies two full city blocks between W. 31st and W. 33rd Streets and 8th and 9th Avenues in the Midtown West area of Manhattan. Directly across 8th Ave. to the east is New York Penn Station, while the Hudson Yards complex is about one block west.

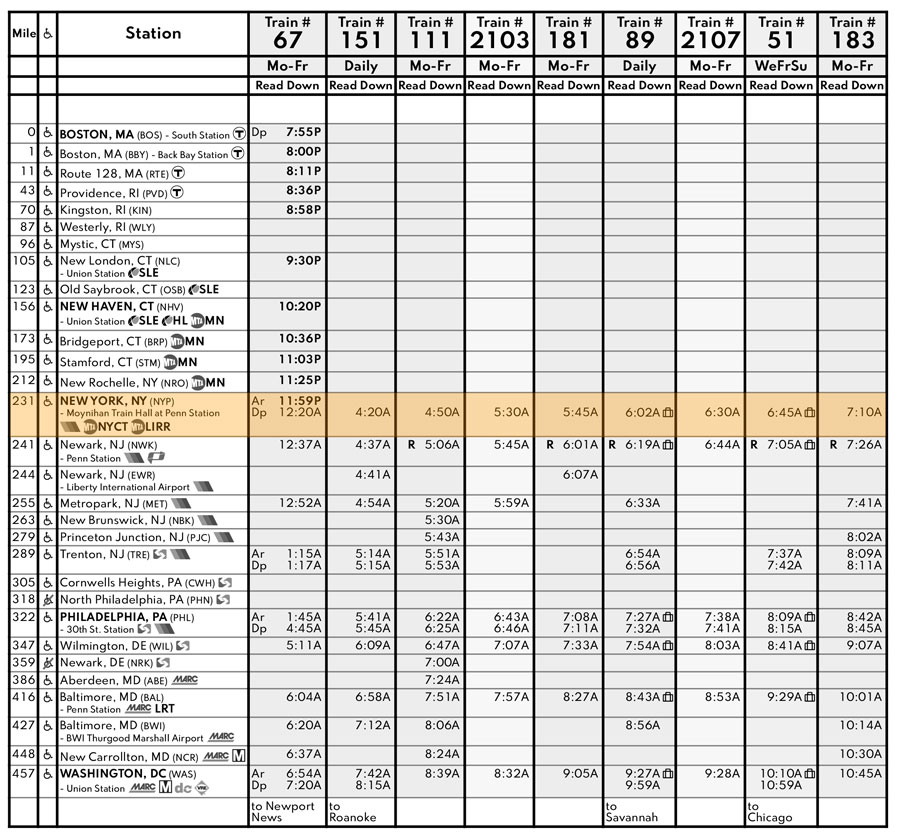

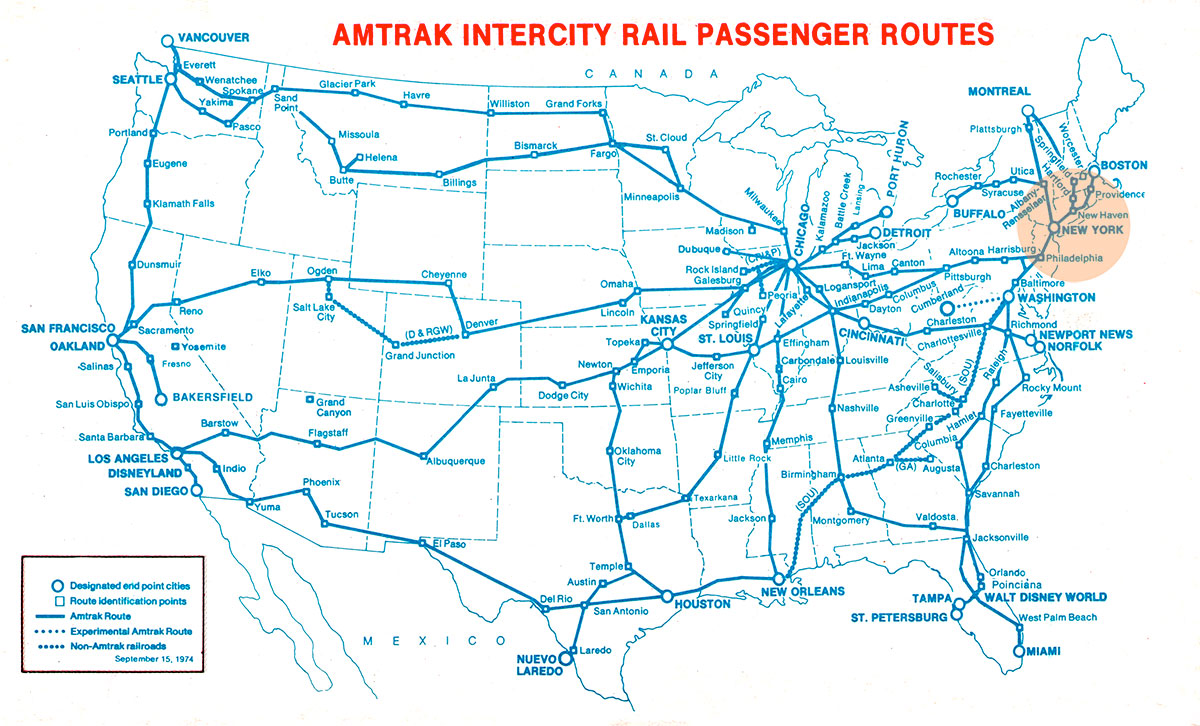

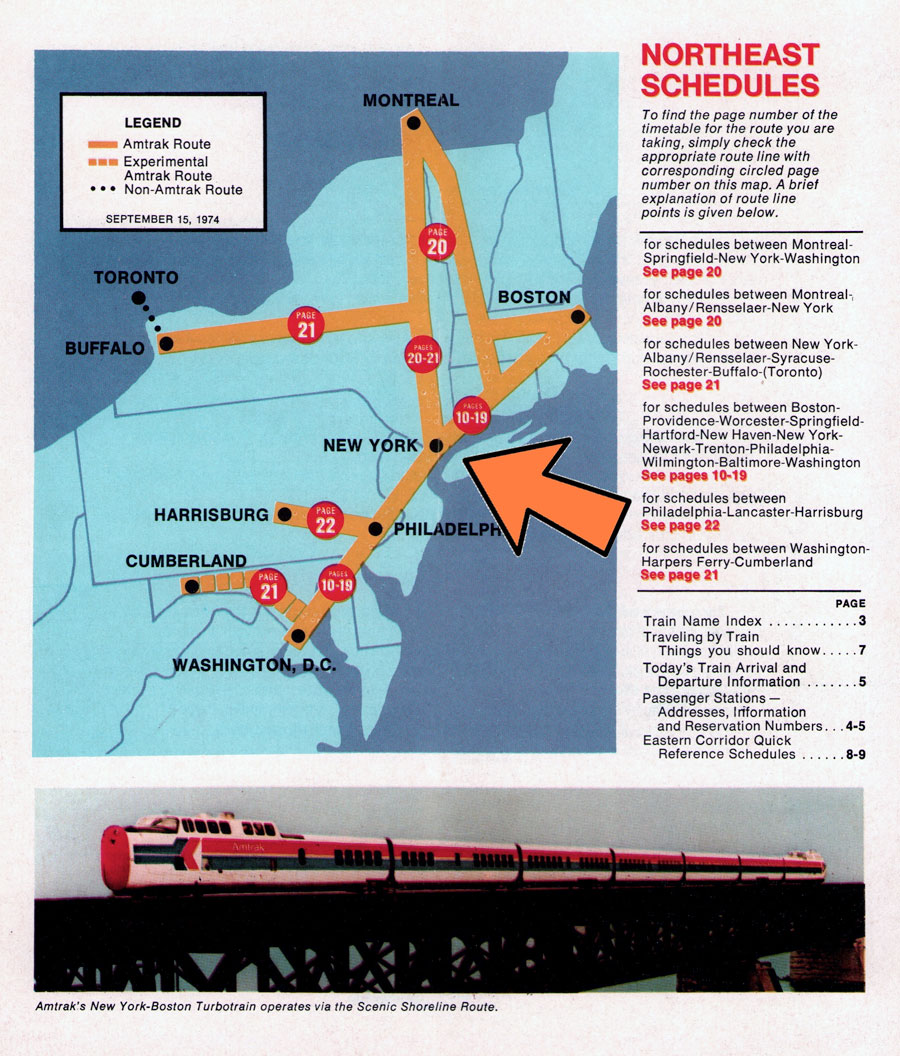

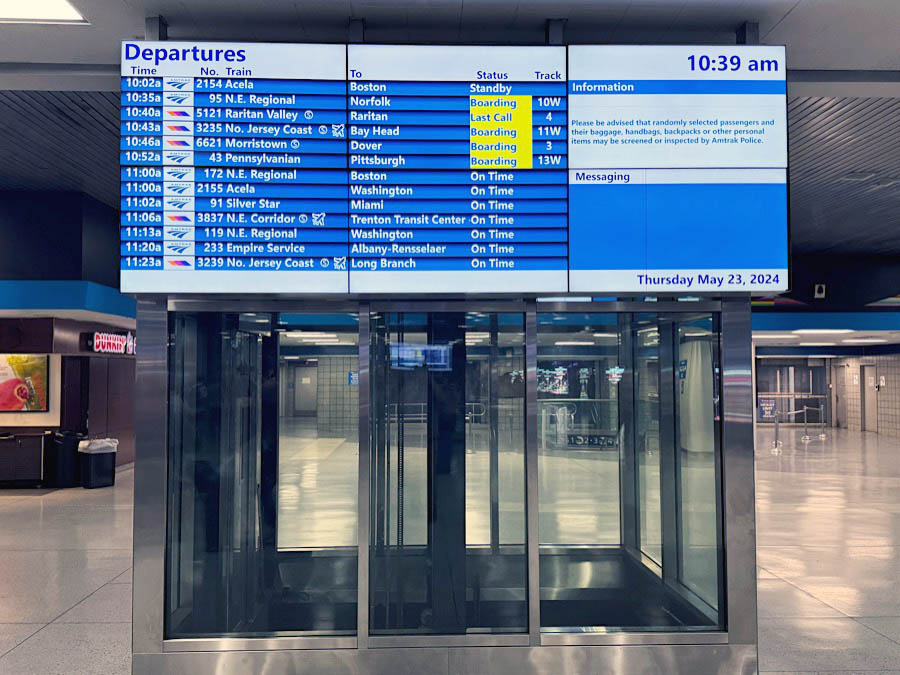

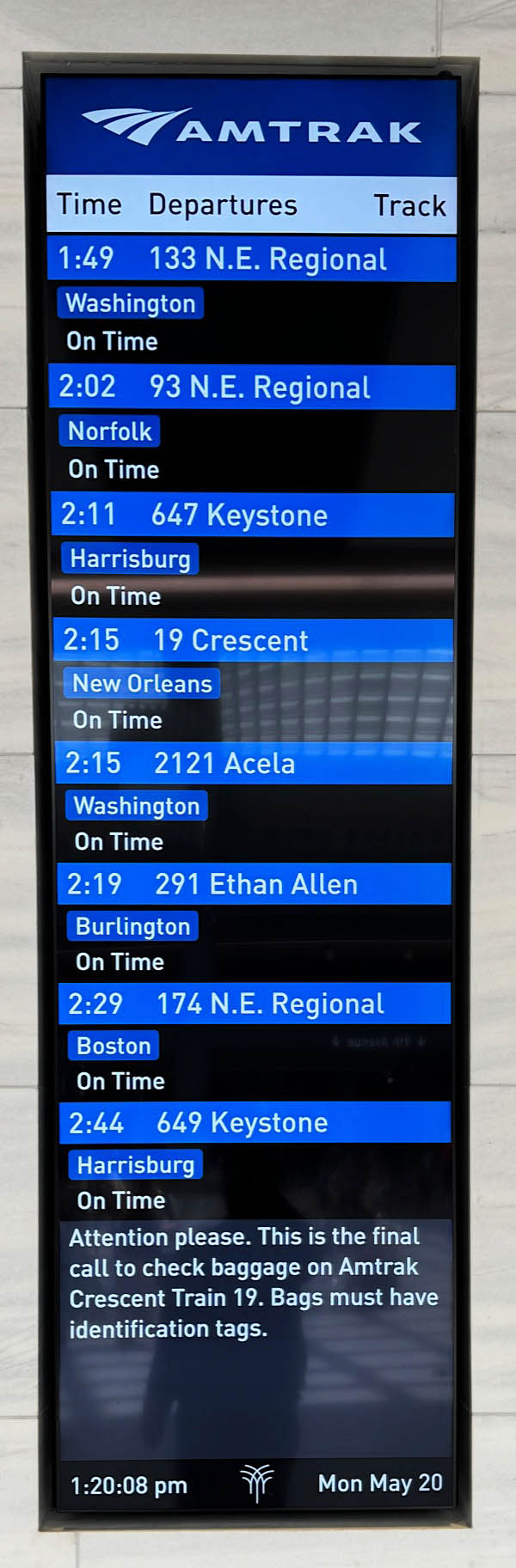

Amtrak customers at New York may board the high-speed Acela or Northeast Regional trains to travel toward Washington, D.C., or Boston, or board numerous short- or long-distance trains whose destinations include Buffalo, Chicago, Miami and New Orleans.

Amtrak customers at New York may board the high-speed Acela or Northeast Regional trains to travel toward Washington, D.C., or Boston, or board numerous short- or long-distance trains whose destinations include Buffalo, Chicago, Miami and New Orleans.

Moynihan Train Hall and New York Penn Station operate as one complex with Amtrak’s full-service offerings available in Moynihan Train Hall between 5 a.m. and 1 a.m. (the Train Hall is closed from 1 a.m. to 5 a.m.). Penn Station remains accessible 24 hours a day as a self-service station, with minimal staff support and limited concourse operations overnight when the Train Hall is closed. Tracks 5-16 can be accessed from the Train Hall main concourse, and Tracks 1-4 are available at Penn Station.

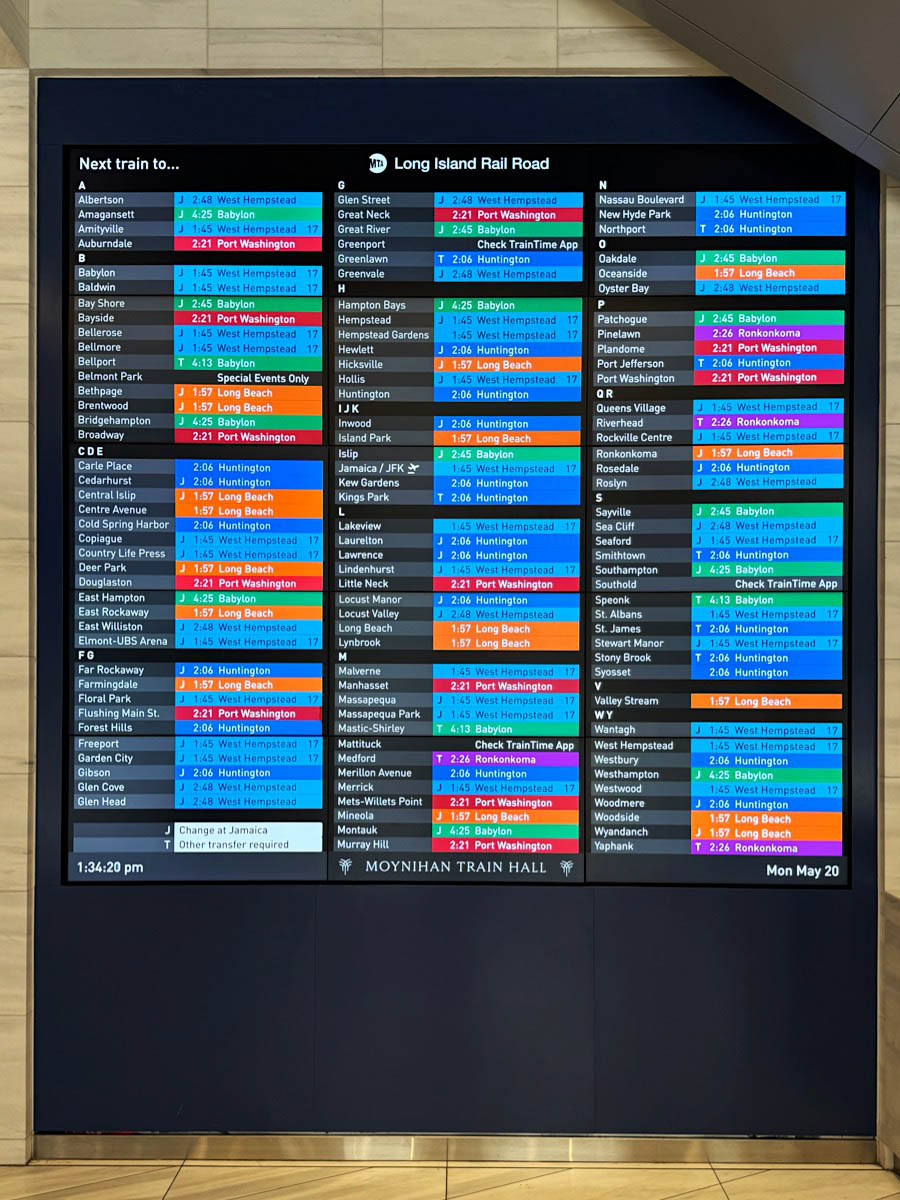

Moynihan Train Hall houses the main Amtrak and Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) boarding concourse, while Penn Station houses the NJ TRANSIT concourse. The Moynihan Train Hall / New York Penn Station complex is readily accessible from more than a dozen lines of the New York City subway (MTA). The Port Authority Trans-Hudson (PATH) rapid transit system has a station nearby at 33rd St. and 6th Ave.

Moynihan Train Hall houses the main Amtrak and Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) boarding concourse, while Penn Station houses the NJ TRANSIT concourse. The Moynihan Train Hall / New York Penn Station complex is readily accessible from more than a dozen lines of the New York City subway (MTA). The Port Authority Trans-Hudson (PATH) rapid transit system has a station nearby at 33rd St. and 6th Ave.

Combined with recent improvements to New York Penn Station, the Moynihan Train Hall helps relieve crowding, improve passenger comfort and security, and offers an enhanced facility that better serves Amtrak and commuter rail passengers. Customers have two paths available between the Train Hall and Penn Station. They can exit Penn Station onto 8th Ave., cross 8th Ave. and enter the Train Hall at any entryway; or, they can walk between the Train Hall and Penn Station on the LIRR concourse level through the Moynihan Lower Concourse. Amtrak’s main entrance to the Moynihan Train Hall is located mid-block on W. 31st St.

Combined with recent improvements to New York Penn Station, the Moynihan Train Hall helps relieve crowding, improve passenger comfort and security, and offers an enhanced facility that better serves Amtrak and commuter rail passengers. Customers have two paths available between the Train Hall and Penn Station. They can exit Penn Station onto 8th Ave., cross 8th Ave. and enter the Train Hall at any entryway; or, they can walk between the Train Hall and Penn Station on the LIRR concourse level through the Moynihan Lower Concourse. Amtrak’s main entrance to the Moynihan Train Hall is located mid-block on W. 31st St.

Today, the platforms are shared among Amtrak, LIRR and NJ TRANSIT. In fall 2020, Amtrak and NJ TRANSIT completed the Ticketed Waiting Area refresh at the Amtrak concourse on the upper level and 8th Ave. side of Penn Station. The project, which included a $7.2 million total joint investment between Amtrak and NJ TRANSIT, features new furniture and fixtures, including seats with electrical and USB outlets to charge devices, an upgraded ceiling complete with new LED lighting, a new information desk and a second entrance in close proximity to the NJ TRANSIT concourse, offering easy access toward the 7th Ave. side of the station, Passenger Information Display System (PIDS) boards that display NJ TRANSIT departure information, and a lactation suite for nursing mothers.

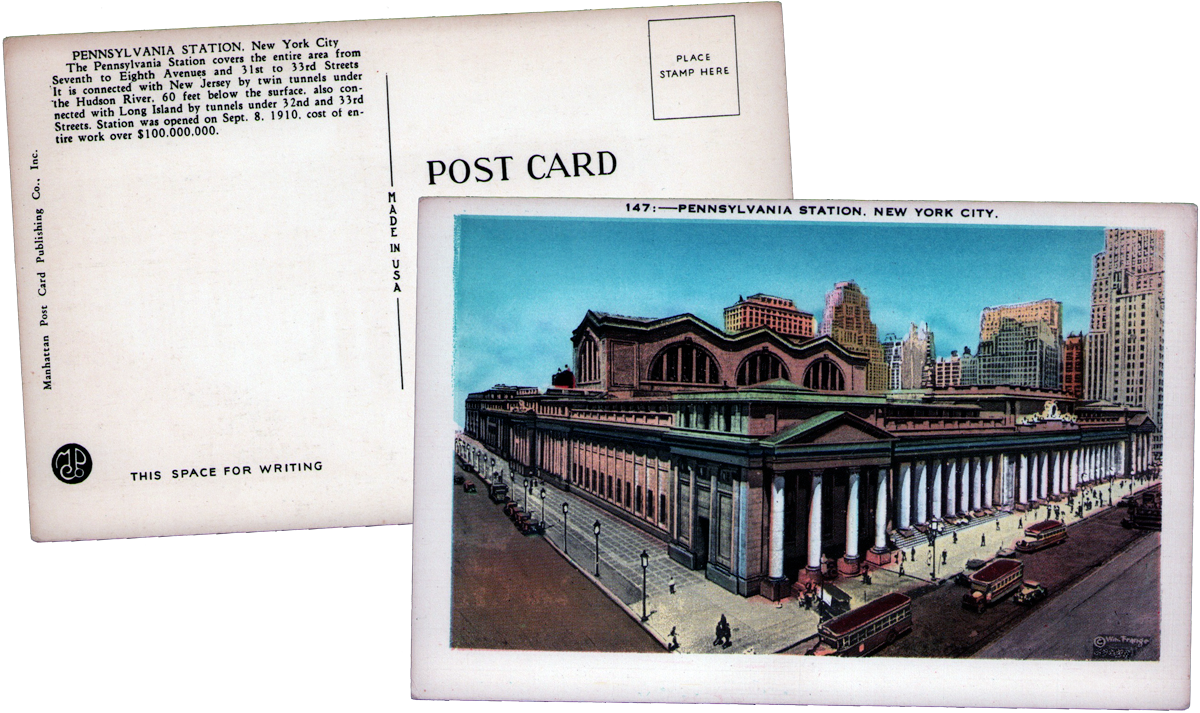

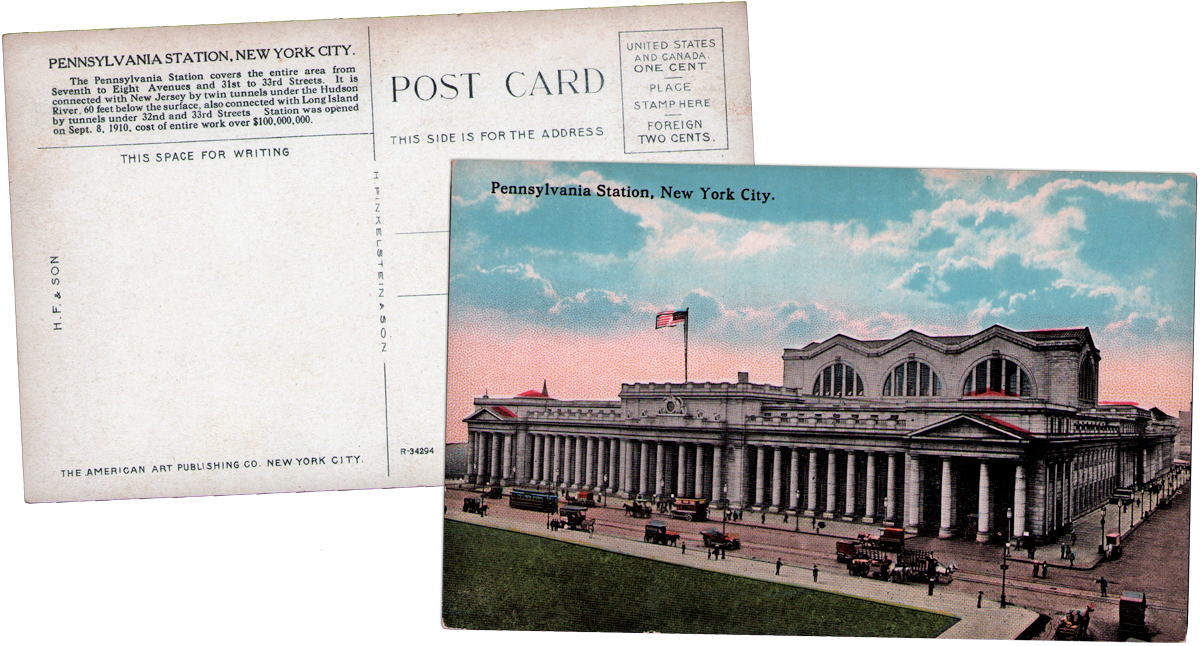

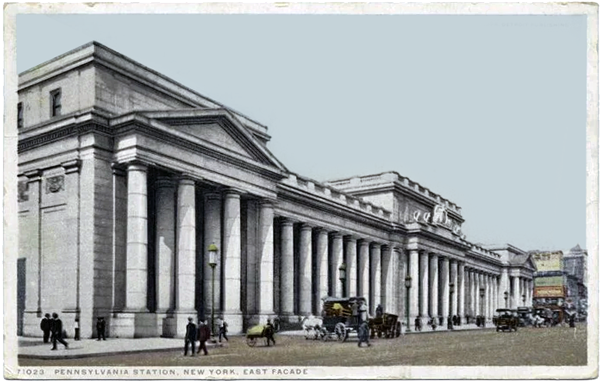

postcard / collection

timetable sample / Rail Passengers Association

New York

- name:Pennsylvania Station

- station code:NYP

- location:7th/9th Avenues and 31st/33rd Streets, NYC

- owner:Amtrak

- operators:Amtrak, PATH, Long Island RR, NJ Transit

- platforms:11 island platforms

- tracks:21 tracks

- opened:original 1910, then replaced 1963

- style:Beaux-Arts

- architect:McKim, Mead, and White

- rebuilt:2020, Moynihan Train Hall expansion

- notes:

- busiest transportation facility in the Western Hemisphere

- routes:

- Northeast Corridor | Adirondack | Berkshire Flyer | Cardinal | Carolinian | Crescent | Ethan Allen | Lake Shore Limited | Maple Leaf | Palmetto | Pennsylvanian | Silver Service | Vermonter

collection

1974 Amtrak timetable map / collection

1974 timetable map / collection

See also our related route scrapbooks:

Original Penn Station

postcard / collection

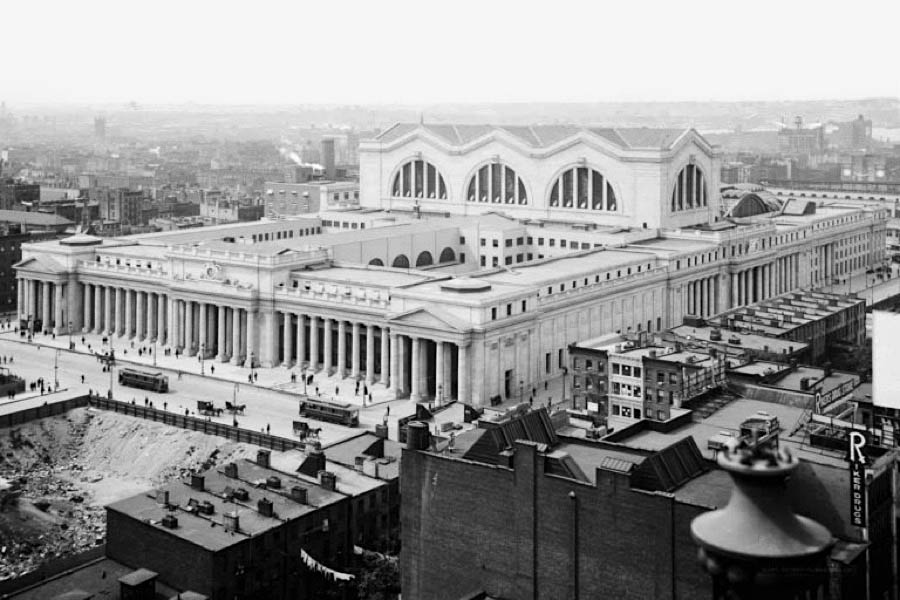

he original Pennsylvania Station, which took the name of its owner and builder, the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR), was opened to the public in the fall of 1910. Considered a masterpiece of neoclassical architecture, the station consisted of an above-ground structure that contained the general waiting rooms, and a complex 50 feet below street level that accommodated 11 platforms. Four platforms continued west where they were accessed by workers at the new main post office – now the Farley building containing the Moynihan Train Hall. When the postal facility opened in 1912, it received about 40 percent of the city’s mail over the PRR lines. Mail sacks were transferred to and from the rail cars through a system of conveyor belts, chutes and slides.

he original Pennsylvania Station, which took the name of its owner and builder, the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR), was opened to the public in the fall of 1910. Considered a masterpiece of neoclassical architecture, the station consisted of an above-ground structure that contained the general waiting rooms, and a complex 50 feet below street level that accommodated 11 platforms. Four platforms continued west where they were accessed by workers at the new main post office – now the Farley building containing the Moynihan Train Hall. When the postal facility opened in 1912, it received about 40 percent of the city’s mail over the PRR lines. Mail sacks were transferred to and from the rail cars through a system of conveyor belts, chutes and slides.

Prior to 1910 and the opening of Pennsylvania Station, trips to New York from the west and the south ended at Jersey City, N.J., on the west side of the Hudson River. The broad Hudson was a formidable obstacle for bridge and tunnel builders, and schemes advanced in the late 19th century would have required vast sums of money to complete even if feasible. Financial panics in the early 1870s and 1890s also precluded any major investments. Railroads instead settled upon ferry service across the watercourse to reach the island of Manhattan.

Prior to 1910 and the opening of Pennsylvania Station, trips to New York from the west and the south ended at Jersey City, N.J., on the west side of the Hudson River. The broad Hudson was a formidable obstacle for bridge and tunnel builders, and schemes advanced in the late 19th century would have required vast sums of money to complete even if feasible. Financial panics in the early 1870s and 1890s also precluded any major investments. Railroads instead settled upon ferry service across the watercourse to reach the island of Manhattan.

In 1871, the PRR leased the New Jersey Railroad for its ferry franchise and water rights on the river. Over the next century, the PRR’s Jersey City station and ferry facility was rebuilt numerous times due to fires. A seven-story terminal, considered the largest in the nation, was completed in 1892 and featured a dramatic single-span roof with a width of 250 feet. After detraining, passengers walked a short distance to the ferry terminal to board one of the double-decker vessels headed for Manhattan, Brooklyn or Staten Island. The busy area around the PRR facilities at Montgomery and Hudson Sts. was popularly known as Exchange Place.

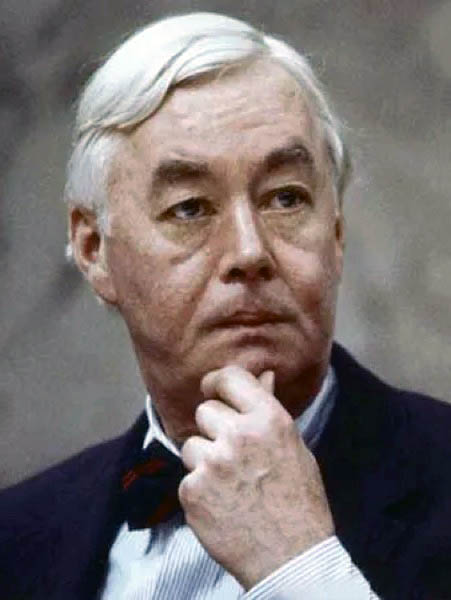

At the end of the 19th century, only two railroads had a terminal in Manhattan: the New York Central (NYC) and the New York, New Haven and Hartford (NYNH&H). Both crossed into Manhattan from the Bronx over the Harlem River. In 1871, the NYC, under the control of Cornelius Vanderbilt, completed the first Grand Central Depot (also used by the NYNH&H) in what is now Midtown East. Alexander Cassatt, a railroad engineer who came out of retirement in 1899 to head the PRR, believed that his railroad also had to obtain a station in New York City, which had become the country’s largest metropolitan area, dominant port and business center. Under his leadership, the railroad weighed its options for crossing the Hudson, eventually settling on a pair of tunnels to run between Weehawken, N.J., and the western Midtown neighborhood of Hell’s Kitchen, known for its brothels and flop houses.

In order to obtain a charter for a bridge, the railroad would have had to share its facilities with other carriers, and so tunnels, although expensive, became a more attractive option. Pennsylvania Station was really just one piece of a larger $114 million (approximately $2.5 billion in today’s money) puzzle that included a new right-of-way from Newark to Manhattan; bridges; tunnels underneath the Hudson and East Rivers and Manhattan; and a new rail yard in Queens. By this point, the city had banned steam locomotives within the urban core. Therefore, the network—including the tunnels—had to be run by the relatively new technology of electric catenaries.

To comply with this mandate, a station known as Manhattan Transfer would be constructed at Harrison, N.J., just east of Newark. Here, trains on the main line stopped to switch to electric locomotives to continue into Manhattan. Those headed for Jersey City and the ferry terminal continued to their destination under steam power. Manhattan Transfer remained in operation until the 1930s when the PRR completed the electrification of its main line. From the station, PRR trains traveled five miles across the Meadowlands to the Bergen Hill portal where they began their descent into the tunnels beneath the Hudson.

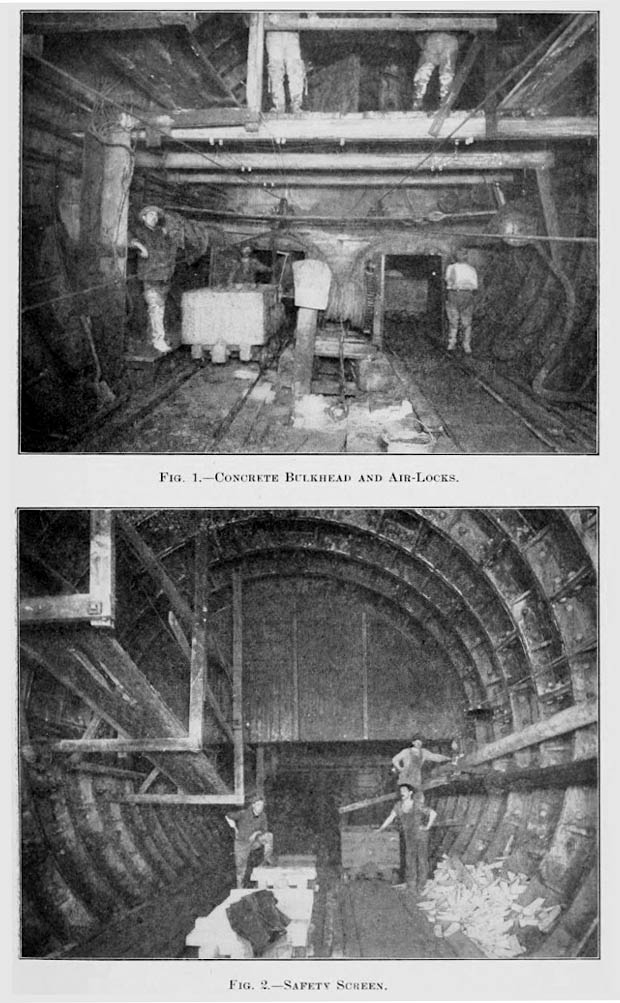

After two years of design work, construction began in 1904 on the pair of single bore tunnels, located 70 feet below the surface of the river. Company engineers used the “shield method,” in which an iron tube was driven forward while compressed air kept out the water. The cast iron tunnel lining is composed of numerous rings, each one being put into place and secured to its predecessor as rock, sand and mud was drilled, blasted and excavated.

After two years of design work, construction began in 1904 on the pair of single bore tunnels, located 70 feet below the surface of the river. Company engineers used the “shield method,” in which an iron tube was driven forward while compressed air kept out the water. The cast iron tunnel lining is composed of numerous rings, each one being put into place and secured to its predecessor as rock, sand and mud was drilled, blasted and excavated.

When the lining was finally completed, workers then coated the interior with a two-foot thick layer of concrete to waterproof and strengthen the structure. The two ends of the northern tube met in 1906. The four single-track tunnels under the East River led to a new rail yard at Sunnyside, Queens, that was used by the PRR and LIRR for the storage and cleaning of trains serving Manhattan. Completed in 1910, Sunnyside sprawled over 192 acres and could accommodate more than 1,000 cars. A loop allowed trains to turn around without the need for a turntable.

Concurrent with the tunnel work, excavation began at the site of Pennsylvania Station. More than 500 houses and other structures had to be removed from the designated blocks, as the above-ground building occupied eight acres while the subterranean concourses and yards stretched across 28 acres. Between 1904 and 1906, the complex rose to an average of 69 feet above street level, or about six stories.

Pennsylvania Station sprang from the creative genius of Charles Follen McKim, one of the principals in the New York-based firm of McKim, Mead and White. The architect and his partners led what was then, and is still now, considered one of the greatest American architectural and design firms. McKim, Mead and White were leading figures of the City Beautiful movement that took hold as the 19th century gave way to the 20th. Led by design professionals and progressives, the movement promoted the improvement of cities through rational order, sanitation and aesthetic enhancement.

This last concept often meant looking back to Roman and Greek precedents that were deemed suitable for a young republic with great ambitions. Many leading City Beautiful proponents attended the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, a design school where the instructors emphasized the need for a logical floor plan coupled with an appropriately dignified architecture embellished through allied arts such as sculpture and painting. Appropriately, McKim, Mead and White based the design of the station on the Baths of Caracalla and the Basilica of Maxentius and Constantine in Rome. Using barrel vaults, both structures had managed to enclose large indoor spaces that accommodated thousands of users.

Upon its completion in summer 1910, Pennsylvania Station was described in glowing superlatives, touted as the biggest, grandest and most modern train station in the nation, and one of the finest in the world. Although giving the impression of solid stone construction, the structure was erected with a steel frame clad in Milford pink granite. Roughly 550,000 cubic feet of stone, 27,000 tons of steel and 15 million bricks were used during construction.

Upon its completion in summer 1910, Pennsylvania Station was described in glowing superlatives, touted as the biggest, grandest and most modern train station in the nation, and one of the finest in the world. Although giving the impression of solid stone construction, the structure was erected with a steel frame clad in Milford pink granite. Roughly 550,000 cubic feet of stone, 27,000 tons of steel and 15 million bricks were used during construction.

On the principal 7th Ave. facade, the architects centered the pedestrian entryway on W. 32nd St. to create a grand vista for travelers approaching from the east. A portico marked by six Doric columns supported a seven-foot diameter clock. It was surrounded by sculptural decoration executed in Tennessee marble by German-born artist Adolph Alexander Weinman. The clocks, which dominated the four porticoed entrances on each side of the building, were adorned with wreaths of leaves upon which leaned two allegorical female figures representing time. Draped in flowing robes, “Day” held a sunflower while “Night” clutched a pair of drooping poppies. Flanking the clocks were trios of eagles, their outstretched wings ready for flight.

Other than Weinman’s pieces, sculptural detail was kept to a minimum, therefore allowing the regular rhythm of the 7th and 8th Ave. colonnades and the pilasters on W. 31st and W. 33rd Sts. to dominate the structure and emphasize its sheer size. Those arriving by automobile or carriage headed to the corner pavilions on 7th Ave. Passing through the colonnade, the roadway descended to a subterranean level where entrances opened directly onto the general waiting room. Following principles taught at the École, the separation of pedestrian and automobile access rationally allowed for easy access and avoided conflict between the two modes. Functional separation was also employed at the LIRR concourse near the corner of 7th Ave and W. 33rd St. where commuter passengers were able to enter and exit the station without passing through the general waiting room.

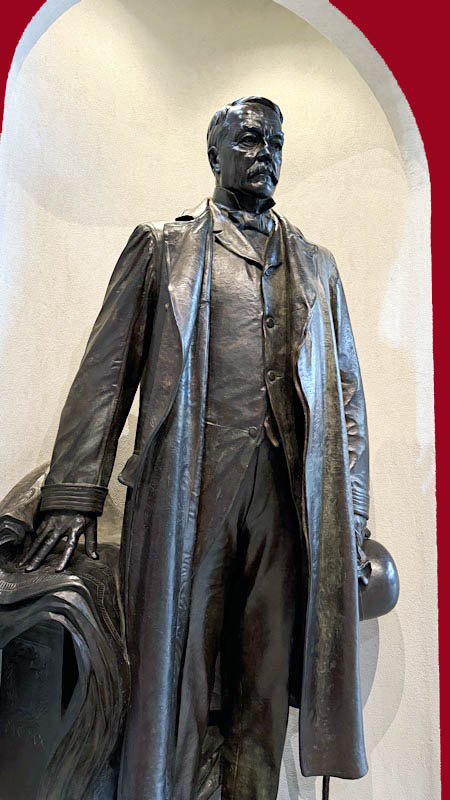

Walking through the 7th Ave. portico, travelers entered a vestibule and then came upon an arcade lined with shop fronts. Modeled after those found in Italian cities such as Milan and Naples, the arcade was brightened by sunlight that streamed through the thermal or “Diocletian” windows. Continuing down the passageway, travelers entered the loggia, which acted as a transition space to the waiting room, reached by a grand staircase. Before descending to the waiting room, passengers had the option of passing to the left or the right through the loggia to enter the dining facilities, which included a lunchroom and a more formal restaurant. A niche in the wall of the loggia held a statue of Cassatt, station plans at his side; he died four years before his railroad triumphantly entered New York City.

Walking through the 7th Ave. portico, travelers entered a vestibule and then came upon an arcade lined with shop fronts. Modeled after those found in Italian cities such as Milan and Naples, the arcade was brightened by sunlight that streamed through the thermal or “Diocletian” windows. Continuing down the passageway, travelers entered the loggia, which acted as a transition space to the waiting room, reached by a grand staircase. Before descending to the waiting room, passengers had the option of passing to the left or the right through the loggia to enter the dining facilities, which included a lunchroom and a more formal restaurant. A niche in the wall of the loggia held a statue of Cassatt, station plans at his side; he died four years before his railroad triumphantly entered New York City.

Moving down the staircase, travelers reached the floor of the waiting room, which was below street level and stretched almost the entire two block width of the building. Above, the plaster ceiling soared to 150 feet, or about 15 stories, and was coffered in a bold octagonal pattern. Barrel vaults running the length and width of the waiting room were visually supported by eight 60-foot tall, seven-foot diameter fluted columns with ornate Corinthian capitals. Their pedestals dwarfed passengers, quickly giving a sense of scale and proportion. Natural light again entered through eight thermal windows, 33 feet high at their midpoints, located just below the roofline. Over the years, countless photographers, both amateur and professional, waited patiently for the perfect moment to permanently capture shafts of light as they penetrated the windows and warmed the passengers below.

Six large panels below the windows were filled with murals depicting maps of the PRR system by painter Jules Guerin, known for luminous illustrations and dramatic perspectives. His soft tones well matched the mellowness of the travertine that covered most of the walls. A favorite building material of the ancient Romans, the stone was a soft yellow-beige color, and gave warmth to large expanses that in darker color tones might seem impersonal and cold. It also had the added benefit of gaining a glowing sheen when touched and rubbed, as was sure to happen with thousands of daily passengers passing through the building. Passenger services such as ticketing and the baggage check were arranged around the perimeter of the waiting room in a sequential fashion so that one could efficiently move from one area to the next without needlessly crisscrossing the vast room.

The destination in one’s westward movement through the station was the concourse, in which the architects made every effort to allow natural light into the space. While the rest of the station emphasized classical grandeur, the 10-story concourse relied on the awe-inspiring power of modern industrial technology. A forest of steel columns supported an extensive system of vaults covered almost entirely in glass. Coupled with glass block embedded into the floor of the passenger galleries surrounding the platforms, light reached all the way down to the tracks, located 36 feet below street level.

Rather than enter the city through a dark and smoky train shed, Pennsylvania Station welcomed travelers with glorious light and soaring spaces unlike those found anywhere else in the nation. The arrival and departure concourses were separated, allowing for the efficient movement of people, and early commentators marveled at the new technology of escalators.

By the mid-20th century, American railroads experienced a decline in passenger traffic as the attraction of modern jet airplane travel and the new Interstate Highway System set the stage for a shift that led passengers away from rail and to these competing travel modes – whose planning and construction were heavily subsidized by the federal government.

Consequently, the vast Pennsylvania Station became a financial burden for the PRR, and in the late 1950s the company optioned the air rights over the facility. From 1963 to 1966, the station building was demolished to make way for the current Madison Square Garden sports and entertainment arena, as well as the 2 Penn Plaza office building. While the new buildings rose above the underground concourses, the trains continued to run, and the present passenger areas were largely completed by spring 1968. In 1984, Amtrak and LIRR undertook a modernization of Penn Station that emphasized improved access for persons with disabilities.

Consequently, the vast Pennsylvania Station became a financial burden for the PRR, and in the late 1950s the company optioned the air rights over the facility. From 1963 to 1966, the station building was demolished to make way for the current Madison Square Garden sports and entertainment arena, as well as the 2 Penn Plaza office building. While the new buildings rose above the underground concourses, the trains continued to run, and the present passenger areas were largely completed by spring 1968. In 1984, Amtrak and LIRR undertook a modernization of Penn Station that emphasized improved access for persons with disabilities.

Considered a “monumental act of vandalism,” the destruction of Pennsylvania Station after only a half-century of service came as a shock to most New Yorkers. Legally, nothing could be done to stop the demolition, and popular outrage over the loss of the grand station prompted the city to institute a historic preservation ordinance and establish the Landmarks Preservation Commission. It also galvanized preservation groups across the country in an era in which federally-sponsored urban renewal efforts, although often well-intentioned, were shattering urban neighborhoods.

Careful, observant explorers can still find remnants of the original Pennsylvania Station, but most of the stone and sculptures were carted off to the New Jersey Meadowlands and dumped into a landfill. Thankfully, some elements were quietly salvaged and later donated to museums. Many of Weinman’s eagles found new perches in cities such as Philadelphia, West Point, N.Y., and Washington, D.C.

Madison Square Garden

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

Click to see the Madison Square Garden complex plotted on a Google Maps page

Post-1968, the core Penn Station has been underground, sitting below Madison Square Garden, 33rd Street, and Two Penn Plaza. The core has three levels: concourses on the upper two levels and train platforms on the lowest. The two levels of concourses, while renovated and expanded during the construction of Madison Square Garden, are original to the 1910 station, as are the tracks and platforms.

Over the following decades, various renovations attempted to add service and some concourse space. The West End Concourse under Eighth Avenue opened in 1986. In 1987, a rail connection to the West Side Rail Yard opened, and in 1991, the opening of the Empire Connection allowed Amtrak to consolidate all of its New York City trains at Penn Station and save $600,000 a year in fees; previously, trains from the Empire Corridor terminated at Grand Central Terminal, a legacy of the two stations' respective roots in separate railroads.

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

Moynihan Train Hall

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

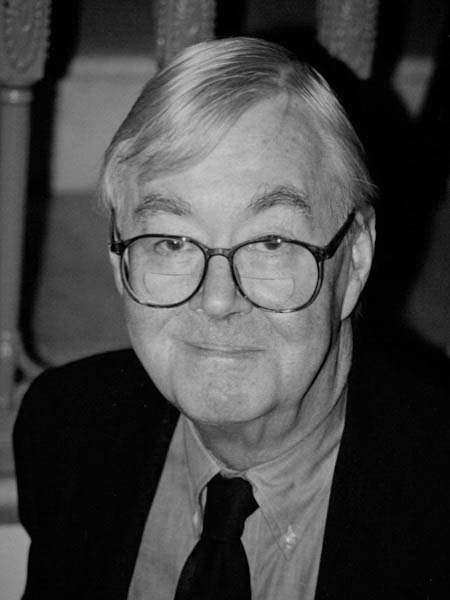

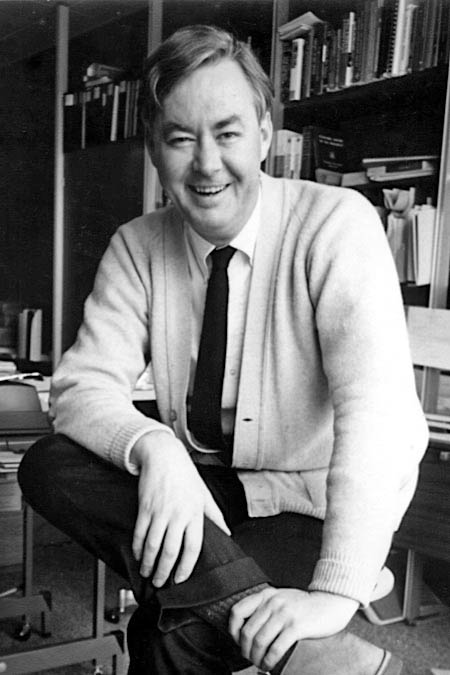

When the above ground portion of Penn Station was destroyed, the city lost one of its great gateways. Subsequently, rail travelers arrived in the city via a warren of underground tunnels that gave out to the street, a seemingly unfitting introduction to a metropolis that dominates the nation’s economic and cultural life. To remedy this perceived deficiency, in the 1990s, Amtrak and Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan proposed using the old post office building—renamed the James A. Farley building in 1982—as the grand ceremonial entrance to the station.

When the above ground portion of Penn Station was destroyed, the city lost one of its great gateways. Subsequently, rail travelers arrived in the city via a warren of underground tunnels that gave out to the street, a seemingly unfitting introduction to a metropolis that dominates the nation’s economic and cultural life. To remedy this perceived deficiency, in the 1990s, Amtrak and Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan proposed using the old post office building—renamed the James A. Farley building in 1982—as the grand ceremonial entrance to the station.

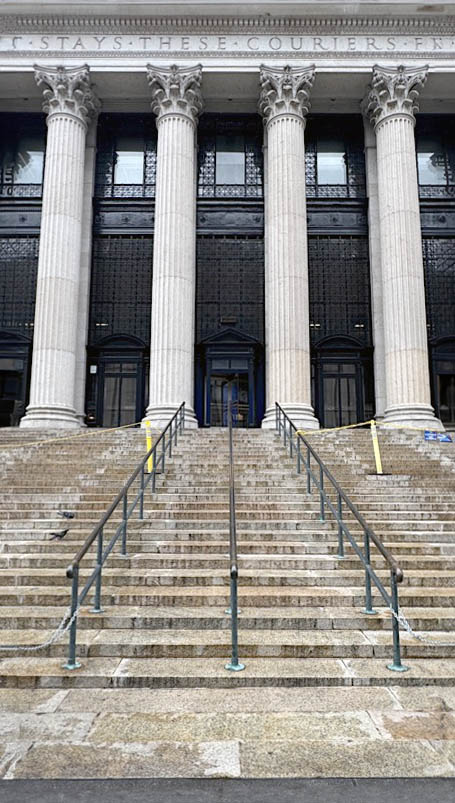

The U.S. Postal Service no longer needed all the space and was considering relocation. Designed in concert with Penn Station by the same architectural firm, the celebrated McKim, Mead and White, the Farley building’s 8th Ave. entrance is marked by a block-long colonnade of Corinthian columns accessed by a ceremonial set of stairs. Inside, the lobby is lighted by soaring windows that show off the intricate, geometric coffered ceiling. After the senator died in 2003, the concept of transforming the Farley building into a transportation facility took the name “Moynihan Station.” Viewing the new rail facility as a plausible catalyst for the redevelopment of the surrounding neighborhoods, the city then rezoned the adjacent blocks to allow for denser commercial development.

Customers find the boarding concourse at the heart of the Moynihan Train Hall, located in what was formerly the Farley building’s mail sorting facility. This spacious open area, approximately the size of Grand Central Terminal’s Main Hall, is paved in Tennessee Quaker marble with escalators leading to the platforms below. Arched steel trusses spanning the room support a four-section vaulted skylight that rises 92 feet above the floor and allows natural light to flood the space throughout the day. From the center of the ceiling hangs a stepped, Art Deco-inspired four-sided clock.

Arrayed around the perimeter of the concourse are the combined Amtrak ticketing and baggage area, reserved customer waiting room – accented with walnut trim that provides a sense of warmth, and a dedicated lactation lounge for nursing mothers. An Amtrak Metropolitan Lounge, a premium lounge space, provides travelers with a high-quality experience, including priority boarding, expanded food and beverage offerings, a family waiting area, dedicated customer service agents, private restrooms and complimentary Wi-Fi. The Moynihan Train Hall also incorporates accessible features that cater to the needs of all Amtrak customers, state-of-the-art wayfinding through dozens of LED and LCD displays, and Red Cap service.

Arrayed around the perimeter of the concourse are the combined Amtrak ticketing and baggage area, reserved customer waiting room – accented with walnut trim that provides a sense of warmth, and a dedicated lactation lounge for nursing mothers. An Amtrak Metropolitan Lounge, a premium lounge space, provides travelers with a high-quality experience, including priority boarding, expanded food and beverage offerings, a family waiting area, dedicated customer service agents, private restrooms and complimentary Wi-Fi. The Moynihan Train Hall also incorporates accessible features that cater to the needs of all Amtrak customers, state-of-the-art wayfinding through dozens of LED and LCD displays, and Red Cap service.

Envisioned for nearly three decades and championed by U.S. Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan of New York, for whom the facility is named, Moynihan Train Hall was designed by architectural firm Skidmore, Owings and Merrill, with interior spaces by Rockwell Group, FX Collaborative and Elkus Manfredi. Overall, the Farley building includes an additional 700,000 square feet of commercial, retail and dining space. As part of the general rehabilitation of the building, which began in 2017, the stone facade, 700 windows, the copper roof and decorative terracotta elements were restored.

Great American Stations / skylight image RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

web

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

esides much needed space, the train hall brings back some of the glamour of Penn Station's original building, which rivaled the storied station across town. The post office building where the renovated hall stands now was originally designed by the same architecture firm that created the original Penn Station—McKim, Mead, and White—in 1913.

esides much needed space, the train hall brings back some of the glamour of Penn Station's original building, which rivaled the storied station across town. The post office building where the renovated hall stands now was originally designed by the same architecture firm that created the original Penn Station—McKim, Mead, and White—in 1913.

“We’ve designed a place that evokes the majesty of the original Penn Station, all while serving as a practical solution to the issues that commuters in, to, and from New York have endured for too long," says Colin Koop, design partner at Skidmore, Owings, & Merrill, the architecture firm behind the new hall. "We are breathing new life into New York, and recreating an experience no one has had here in decades.”

May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

he Moynihan Train Hall project first emerged decades ago as the leading strategy to address many of the station’s most notorious issues and overcame countless hurdles thanks to persistent leadership from the community and elected officials. The extraordinary civic project to convert the 1913 Beaux-Arts Farley Building into a 21st Century train station has been decades in the making, with Skidmore, Owings & Merrill leading the architectural redesign as the initiative evolved.

he Moynihan Train Hall project first emerged decades ago as the leading strategy to address many of the station’s most notorious issues and overcame countless hurdles thanks to persistent leadership from the community and elected officials. The extraordinary civic project to convert the 1913 Beaux-Arts Farley Building into a 21st Century train station has been decades in the making, with Skidmore, Owings & Merrill leading the architectural redesign as the initiative evolved.

“You don’t get a second chance like this often. We must do it.” – Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

James A. Farley Building

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

Click to see the James A. Farley Building plotted on a Google Maps page

The James A. Farley Building is a mixed-use structure in Midtown Manhattan, New York City, which formerly served as the city's main United States Postal Service (USPS) branch. Designed by McKim, Mead & White in the Beaux-Arts style, the structure was built between 1911 and 1914, with an annex constructed between 1932 and 1935. The Farley Building, at 421 Eighth Avenue between 31st Street and 33rd Street in Midtown Manhattan, faces Pennsylvania Station and Madison Square Garden to the east.

The James A. Farley Building is a mixed-use structure in Midtown Manhattan, New York City, which formerly served as the city's main United States Postal Service (USPS) branch. Designed by McKim, Mead & White in the Beaux-Arts style, the structure was built between 1911 and 1914, with an annex constructed between 1932 and 1935. The Farley Building, at 421 Eighth Avenue between 31st Street and 33rd Street in Midtown Manhattan, faces Pennsylvania Station and Madison Square Garden to the east.

The main facade of the Farley Building (over 8th Avenue) features a Corinthian colonnade finishing at a pavilion on each end. The imposing design was meant to match that of the original Pennsylvania Station across the street. An entablature above the colonnade bears the United States Postal Service creed: "Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds." The colonnade's inner ceiling is decorated with the crests or emblems of ten major nations that existed at the building's completion. The remaining three facades have a similar but simpler design.

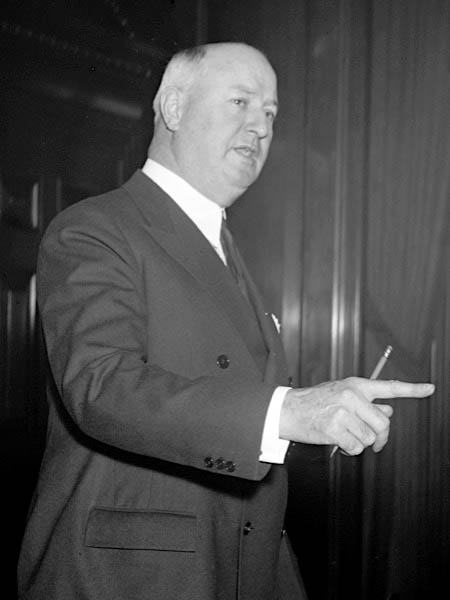

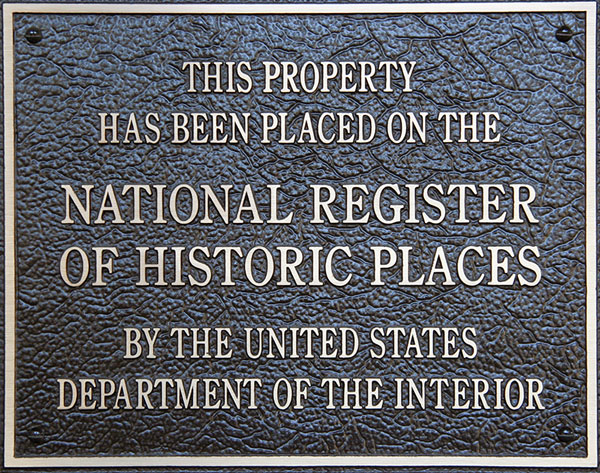

The James A. Farley Building was known as the Pennsylvania Terminal until 1918, when it was renamed the General Post Office Building. The building was made a New York City designated landmark in 1966 and was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1973. It was officially renamed in 1982 in honor of James Farley who was the nation's 53rd postmaster general and served from 1933 to 1940. The building was sold to the New York government in 2006. The interior space that once housed the main mail sorting room now houses the Moynihan Train Hall since 2021. Office space in the building was leased to Facebook in 2020.

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

Lagniappe

Under the World's Most Famous Arena

May 2024 / image and artwork RWH

Cityscape Gate

May 2024 / RWH

Sunlight: Then and Now

upper: collection / lower: May 2024 RWH

"We must do it.” – Daniel Patrick Moynihan

image and artwork RWH

Hub of the Hemisphere

image and artwork RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

Snapshots

Snapshots

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

New York, NY / May 2024 / RWH

Links / Sources

- Moynihan Train Hall NYC website

- Amtrak's Penn Station page

- Great American Stations Penn Station page

- Amtrak Guide Penn Station page

- Wikipedia article for Penn Station

At the end of the 19th century, only two railroads had a terminal in Manhattan: the New York Central (NYC) and the New York, New Haven and Hartford (NYNH&H). Both crossed into Manhattan from the Bronx over the Harlem River. In 1871, the NYC, under the control of Cornelius Vanderbilt, completed the first Grand Central Depot (also used by the NYNH&H) in what is now Midtown East. Alexander Cassatt, a railroad engineer who came out of retirement in 1899 to head the PRR, believed that his railroad also had to obtain a station in New York City, which had become the country’s largest metropolitan area, dominant port and business center. Under his leadership, the railroad weighed its options for crossing the Hudson, eventually settling on a pair of tunnels to run between Weehawken, N.J., and the western Midtown neighborhood of Hell’s Kitchen, known for its brothels and flop houses.

At the end of the 19th century, only two railroads had a terminal in Manhattan: the New York Central (NYC) and the New York, New Haven and Hartford (NYNH&H). Both crossed into Manhattan from the Bronx over the Harlem River. In 1871, the NYC, under the control of Cornelius Vanderbilt, completed the first Grand Central Depot (also used by the NYNH&H) in what is now Midtown East. Alexander Cassatt, a railroad engineer who came out of retirement in 1899 to head the PRR, believed that his railroad also had to obtain a station in New York City, which had become the country’s largest metropolitan area, dominant port and business center. Under his leadership, the railroad weighed its options for crossing the Hudson, eventually settling on a pair of tunnels to run between Weehawken, N.J., and the western Midtown neighborhood of Hell’s Kitchen, known for its brothels and flop houses.

The James A. Farley Building was known as the Pennsylvania Terminal until 1918, when it was renamed the General Post Office Building. The building was made a New York City designated landmark in 1966 and was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1973. It was officially renamed in 1982 in honor of James Farley who was the nation's 53rd postmaster general and served from 1933 to 1940. The building was sold to the New York government in 2006. The interior space that once housed the main mail sorting room now houses the Moynihan Train Hall since 2021. Office space in the building was leased to Facebook in 2020.

The James A. Farley Building was known as the Pennsylvania Terminal until 1918, when it was renamed the General Post Office Building. The building was made a New York City designated landmark in 1966 and was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1973. It was officially renamed in 1982 in honor of James Farley who was the nation's 53rd postmaster general and served from 1933 to 1940. The building was sold to the New York government in 2006. The interior space that once housed the main mail sorting room now houses the Moynihan Train Hall since 2021. Office space in the building was leased to Facebook in 2020.