|

Presbyterian Heritage CenterRemembering Montreat's Mount Mitchell Railroad |

collection

oday, you can drive a scenic highway almost all the way to the crest of the highest elevation east of the Mississippi. As an old mountain ballad noted, it wasn’t always so easy: “It’s a long hike to old Mt. Mitchell, it’s a long way to go,” the song went. “It’s a long hike to old Mt. Mitchell, the highest peak I know.”

Scaling the 6,683-foot mountain was indeed a hard slog. After all, Elisha Mitchell, who famously documented Mt. Mitchell’s height and posthumously gave his name to it, plunged to his death there during a climb in 1857. But early in the 20th century, commercial explorers created motorized routes that put Mt. Mitchell’s summit increasingly within reach.

oday, you can drive a scenic highway almost all the way to the crest of the highest elevation east of the Mississippi. As an old mountain ballad noted, it wasn’t always so easy: “It’s a long hike to old Mt. Mitchell, it’s a long way to go,” the song went. “It’s a long hike to old Mt. Mitchell, the highest peak I know.”

Scaling the 6,683-foot mountain was indeed a hard slog. After all, Elisha Mitchell, who famously documented Mt. Mitchell’s height and posthumously gave his name to it, plunged to his death there during a climb in 1857. But early in the 20th century, commercial explorers created motorized routes that put Mt. Mitchell’s summit increasingly within reach.

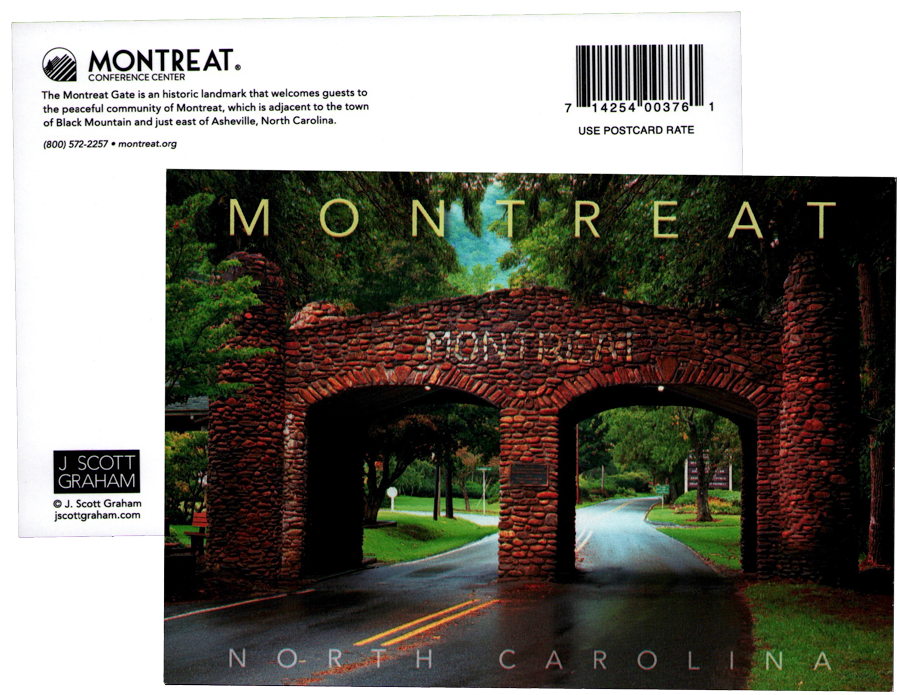

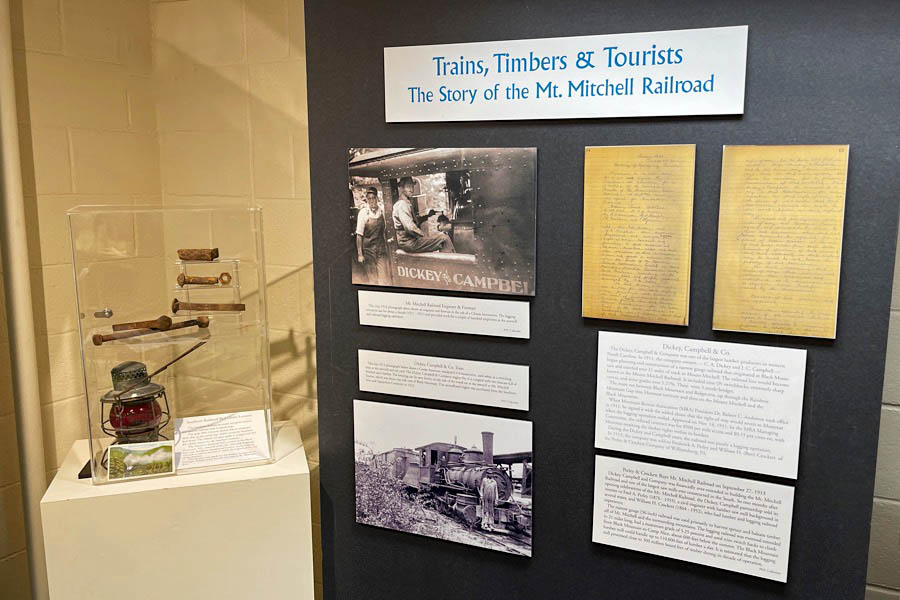

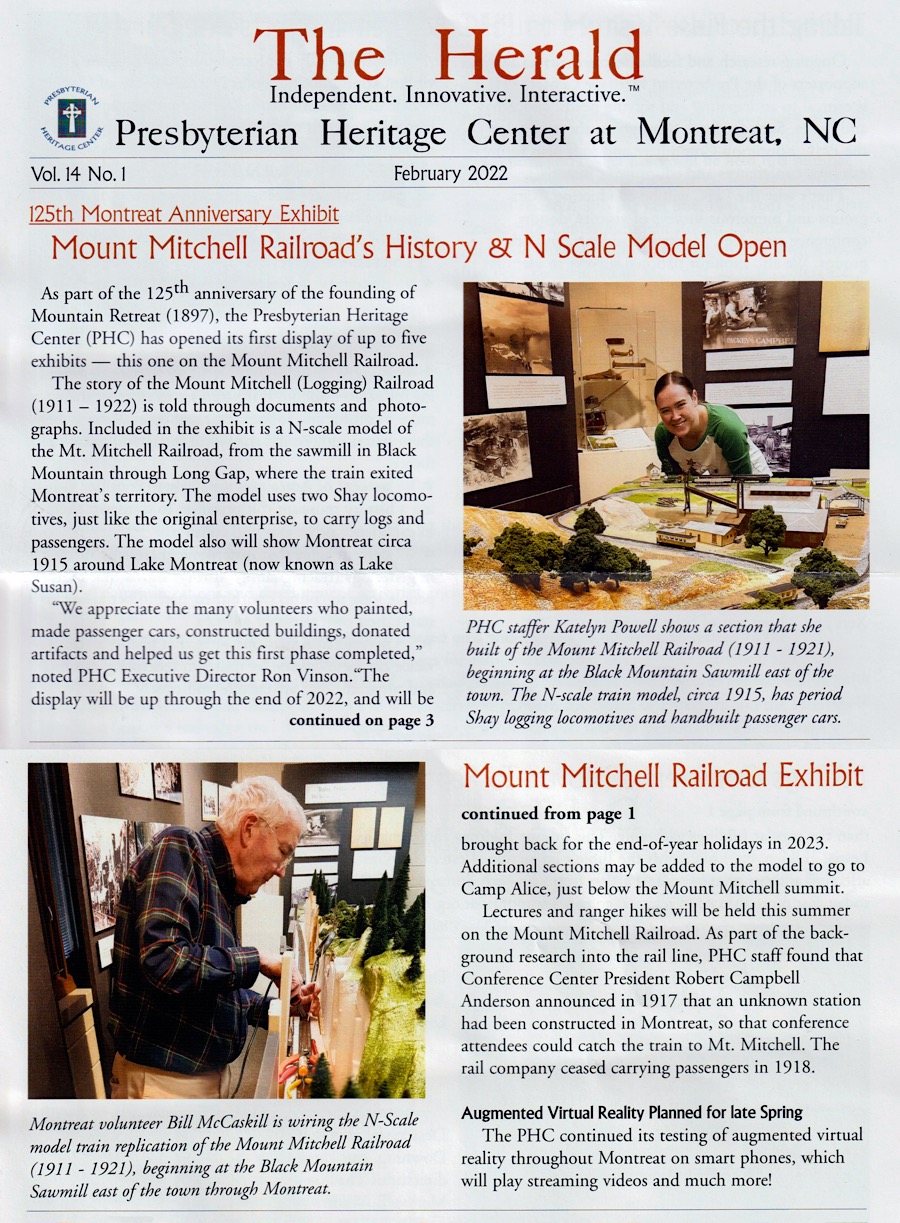

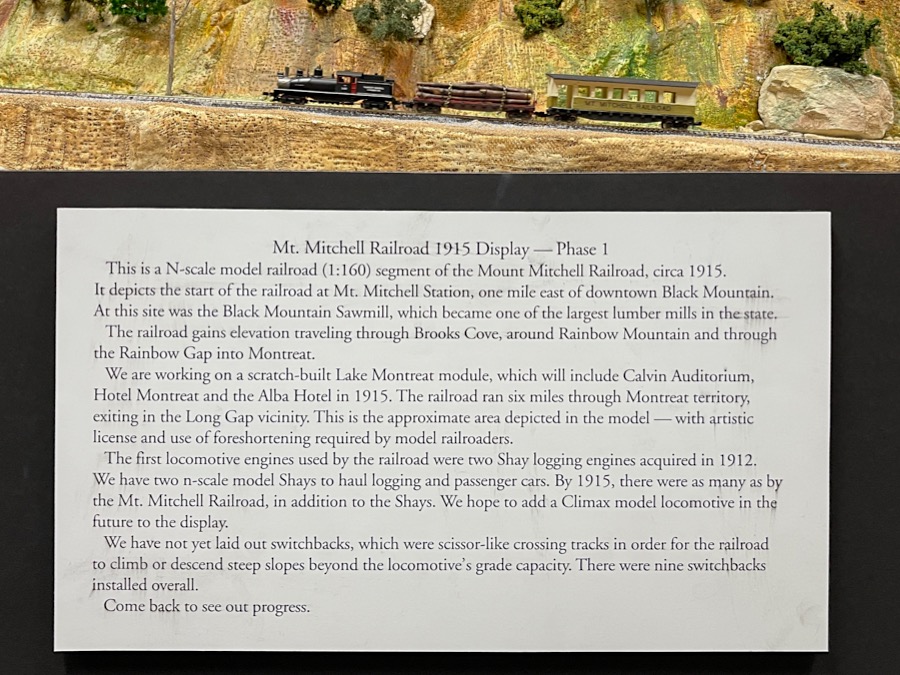

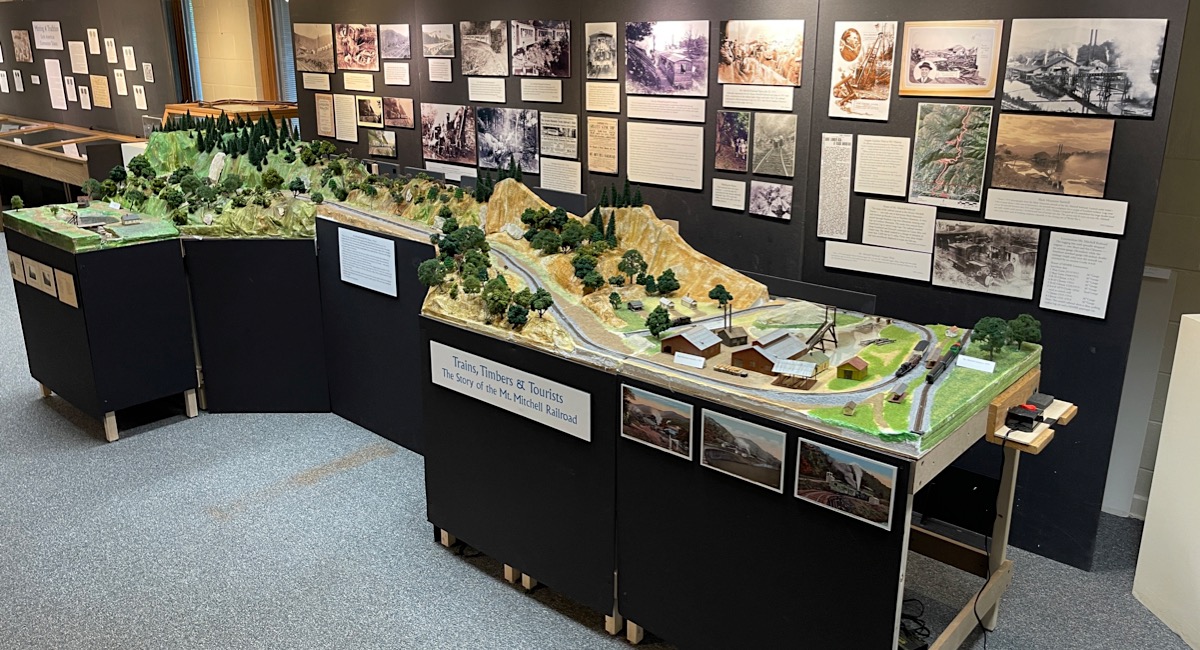

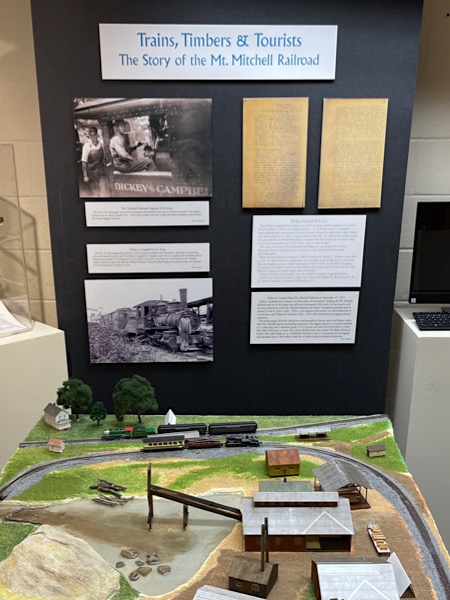

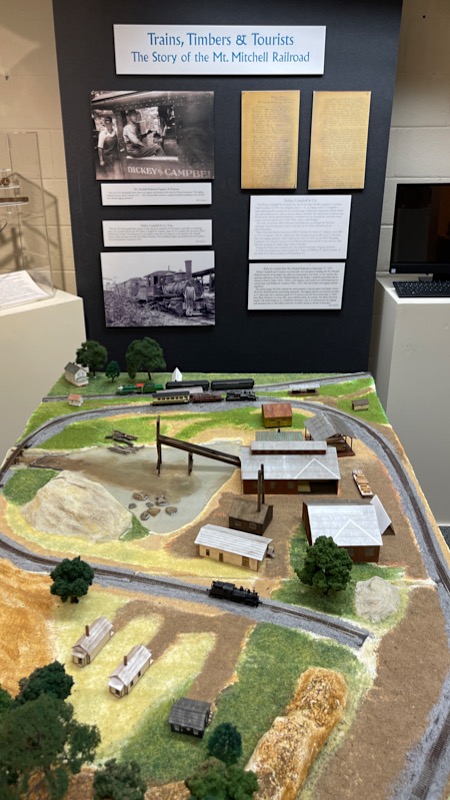

Located in beautiful Montreat, North Carolina, east of Asheville, the Presbyterian Heritage Center is an independent non-profit organization dedicated to collecting and preserving records and materials of all the Presbyterian and Reformed churches in the region. The PHC is the successor to the Friends of the Historical Foundation, whose mission was to support the former Historical Foundation operation in Montreat before its parent denomination closed that facility to consolidate its materials with another Foundation in Philadelphia. Among many exhibits and displays that interpret Presbyterian history in the region, the Center constructed an N-scale layout and related displays to interpret the history of the nearby Mt. Mitchell Railroad.

Located in beautiful Montreat, North Carolina, east of Asheville, the Presbyterian Heritage Center is an independent non-profit organization dedicated to collecting and preserving records and materials of all the Presbyterian and Reformed churches in the region. The PHC is the successor to the Friends of the Historical Foundation, whose mission was to support the former Historical Foundation operation in Montreat before its parent denomination closed that facility to consolidate its materials with another Foundation in Philadelphia. Among many exhibits and displays that interpret Presbyterian history in the region, the Center constructed an N-scale layout and related displays to interpret the history of the nearby Mt. Mitchell Railroad.

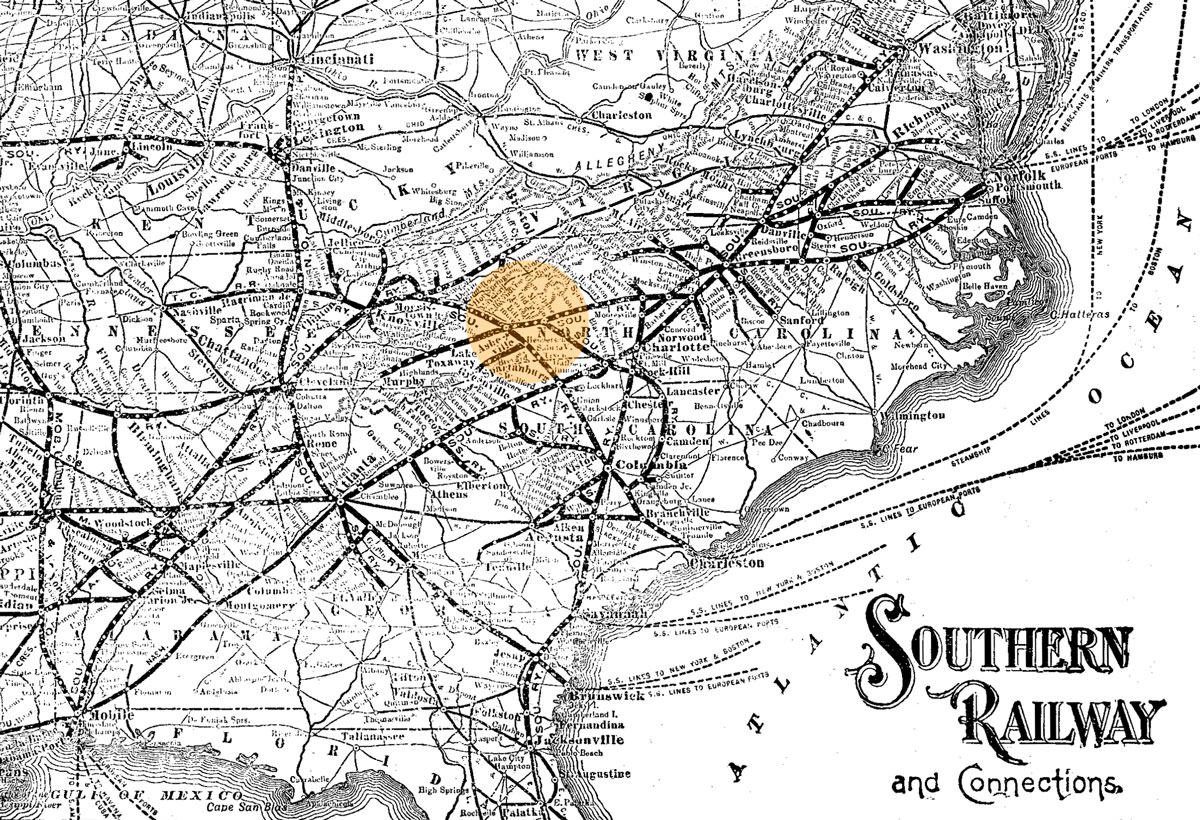

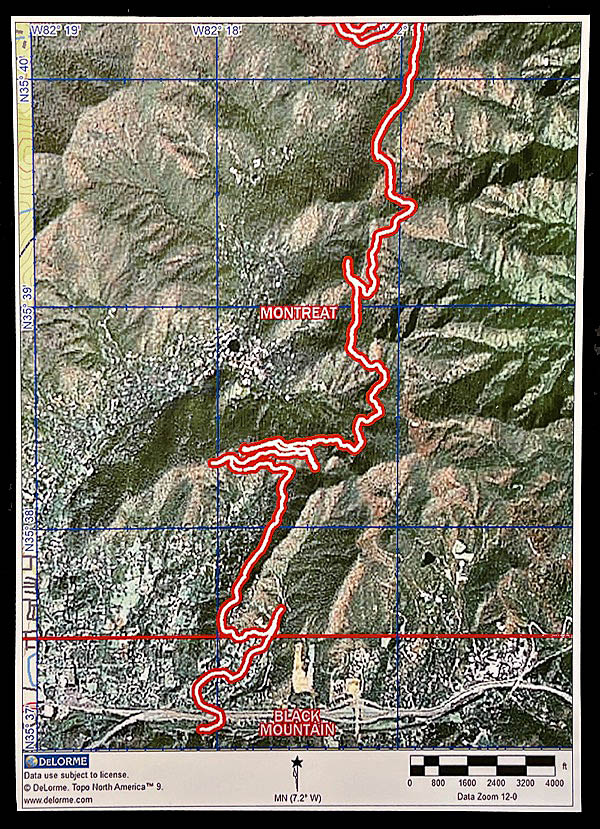

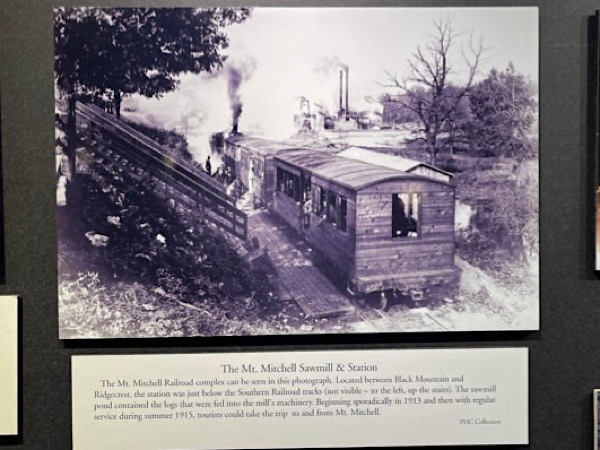

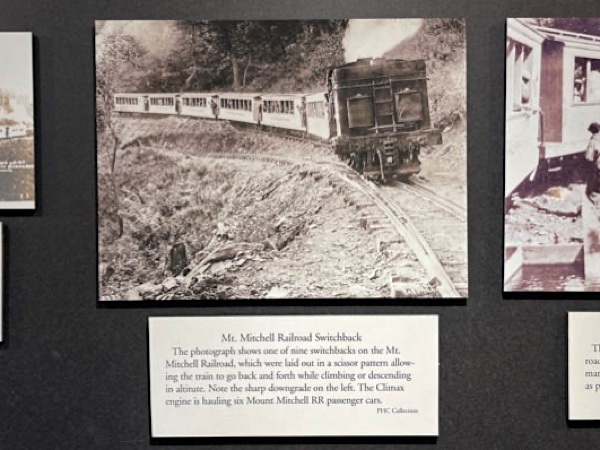

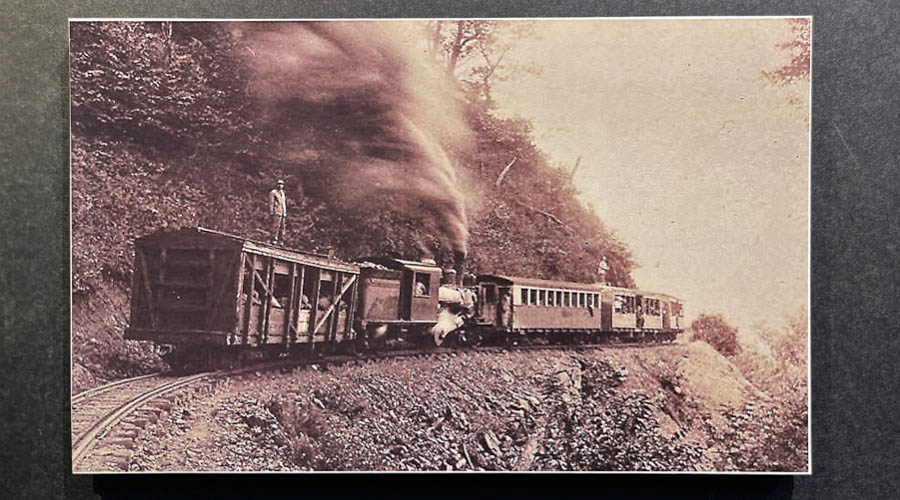

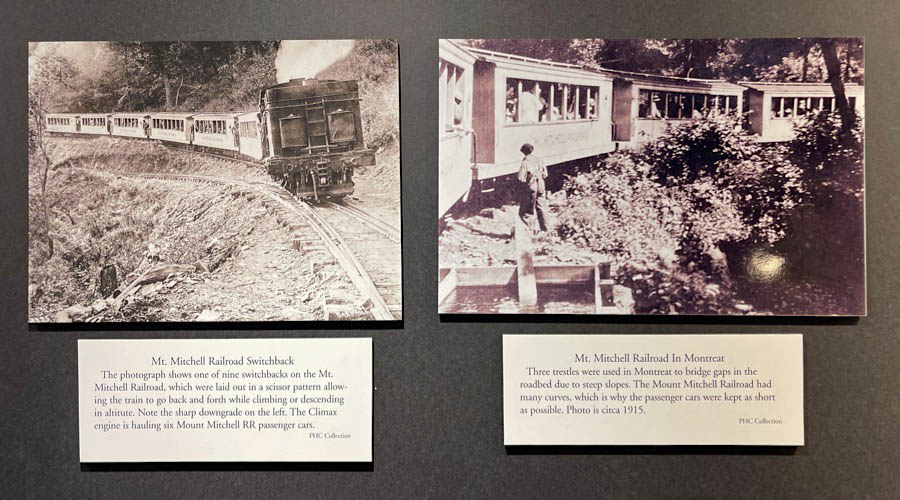

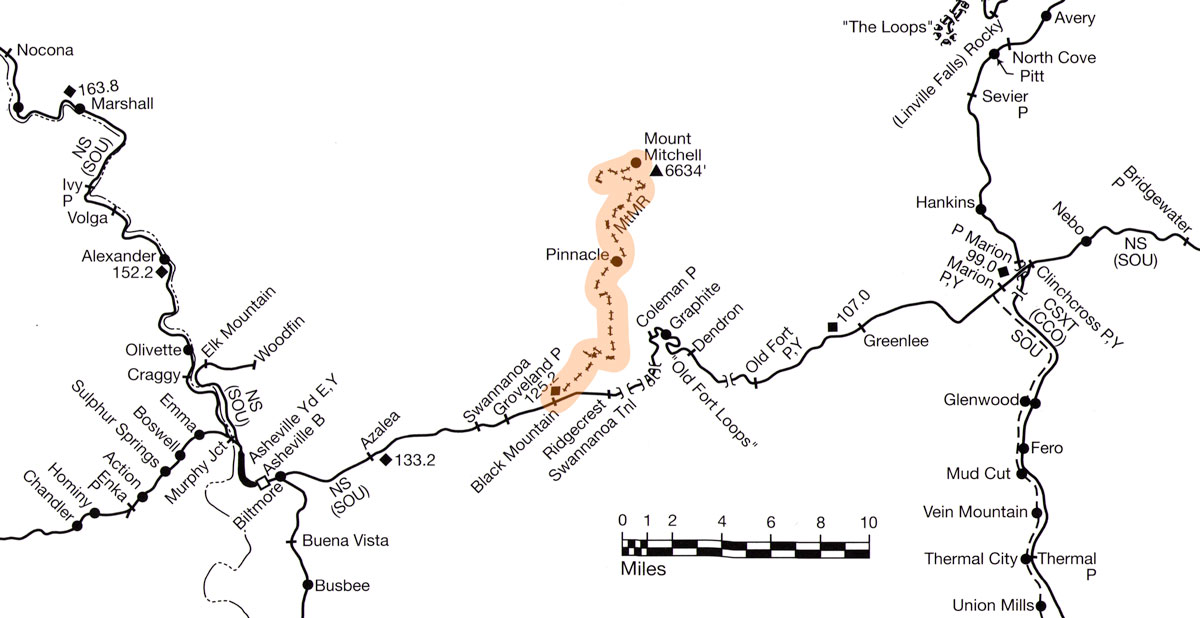

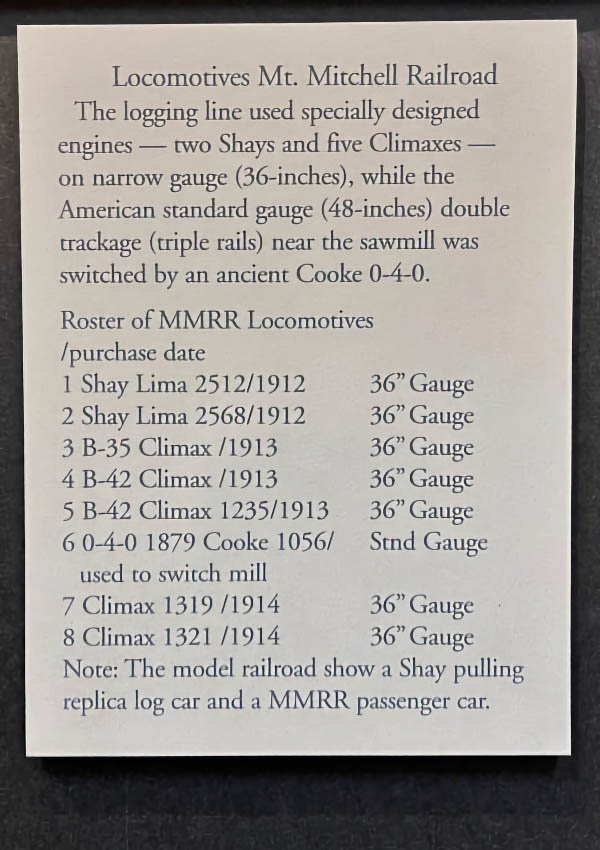

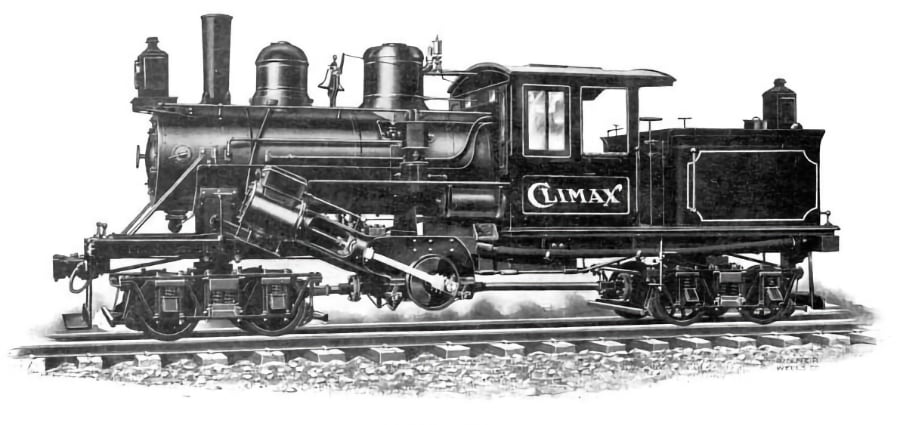

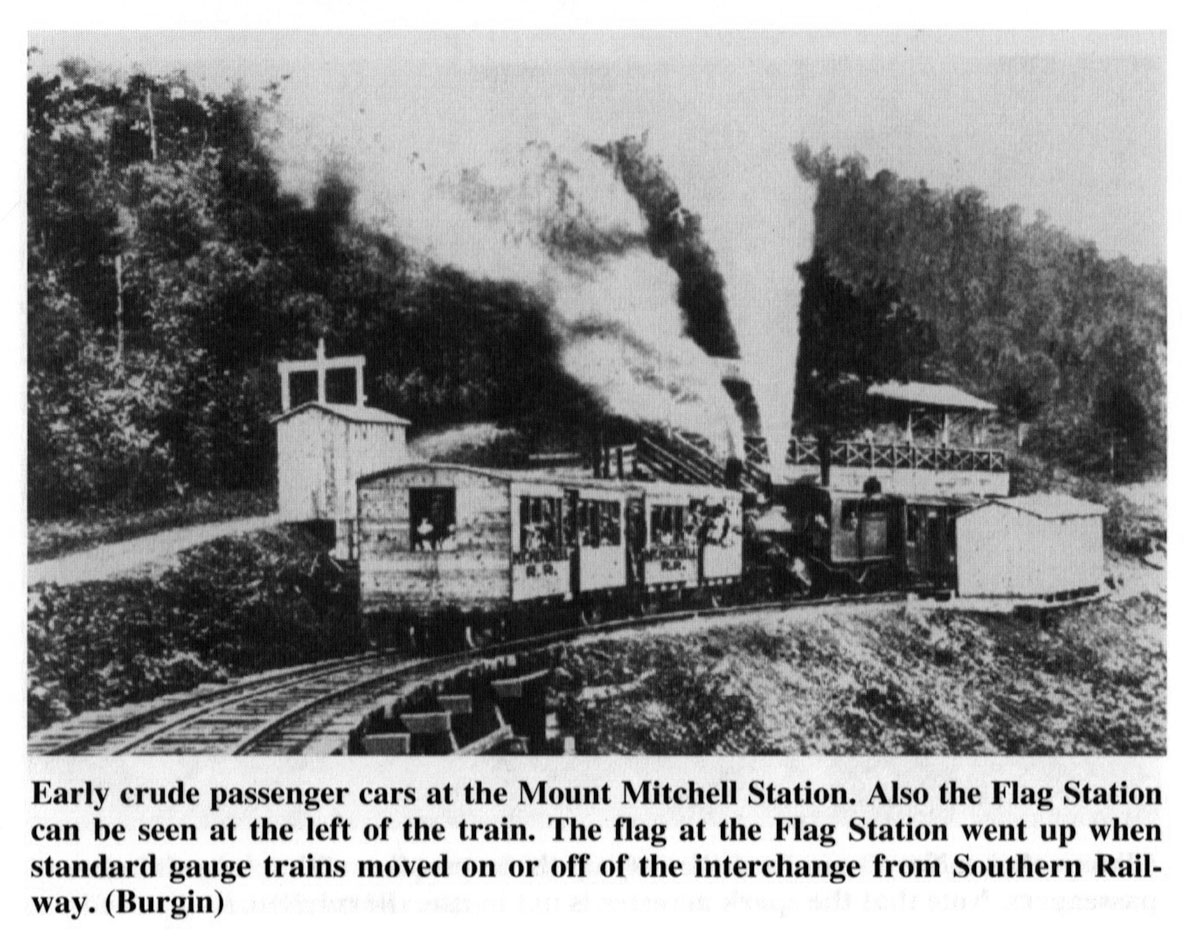

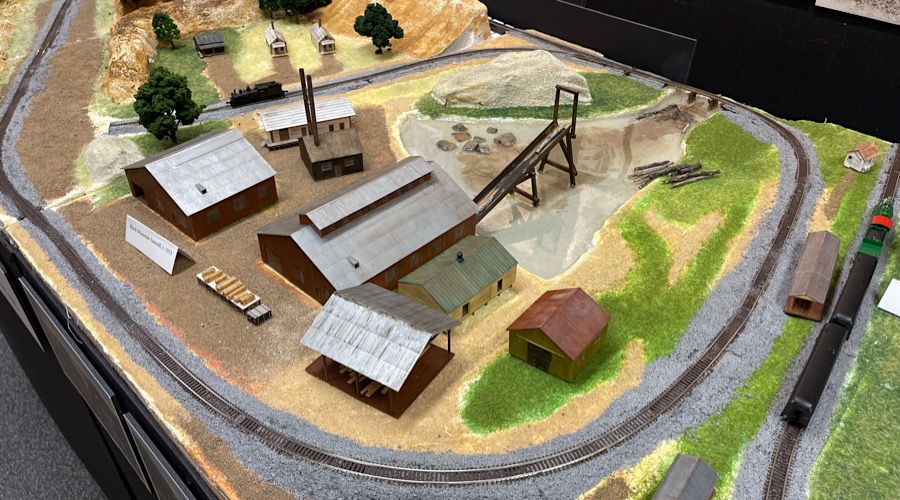

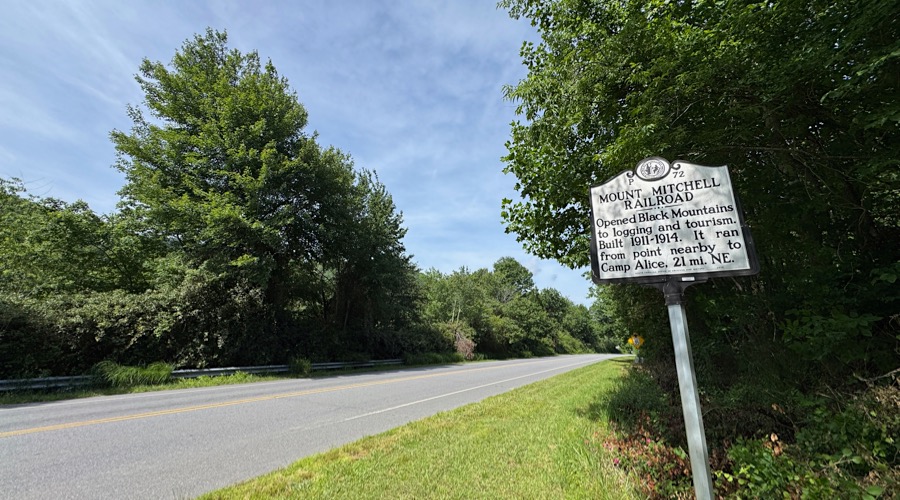

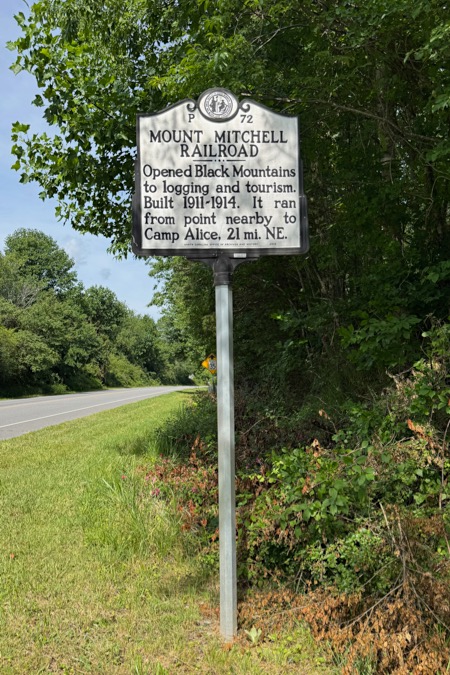

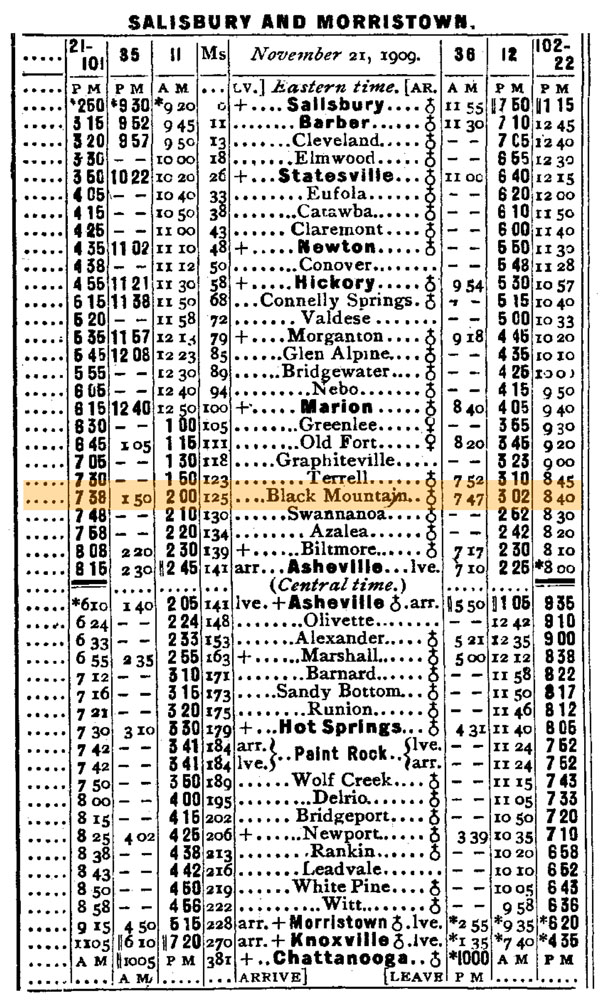

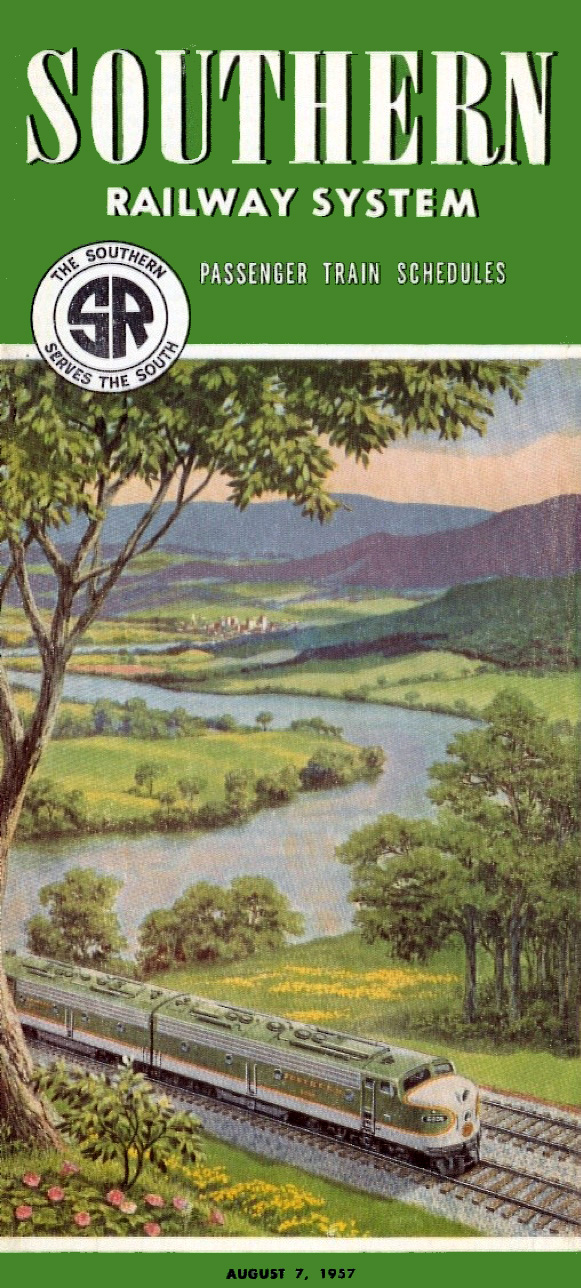

The Mt. Mitchell Railroad was a narrow gauge logging and tourist railway operation in western North Carolina during the early 20th century. Constructed in 1911 by the Dickey & Campbell Company as a logging line to support timber operations in the rugged Blue Ridge Mountains, it ran approximately 21 miles from a Southern Railway connection at Black Mountain to Camp Alice near the summit of Mount Mitchell — the highest peak east of the Mississippi River. The line included nine switchbacks, extremely sharp curves, and some grades over 5 percent. In 1913, the line and its sawmill were purchased by Perley & Crockett Lumber Company, who expanded the operation and run it until 1920 when the short-lived Mount Mitchell Scenic Railroad was formed to carry passengers after logging operations ceased in the area. Though popular with tourists, the railroad’s steep grades, switchbacks, and maintenance costs in the harsh mountain environment led to its closure in 1921 in favor of a toll road. Today, remnants of the route are preserved in hiking trails and historical markers along the route to Mount Mitchell, including near the Montreat Camp and Conference Center.

The Mt. Mitchell Railroad was a narrow gauge logging and tourist railway operation in western North Carolina during the early 20th century. Constructed in 1911 by the Dickey & Campbell Company as a logging line to support timber operations in the rugged Blue Ridge Mountains, it ran approximately 21 miles from a Southern Railway connection at Black Mountain to Camp Alice near the summit of Mount Mitchell — the highest peak east of the Mississippi River. The line included nine switchbacks, extremely sharp curves, and some grades over 5 percent. In 1913, the line and its sawmill were purchased by Perley & Crockett Lumber Company, who expanded the operation and run it until 1920 when the short-lived Mount Mitchell Scenic Railroad was formed to carry passengers after logging operations ceased in the area. Though popular with tourists, the railroad’s steep grades, switchbacks, and maintenance costs in the harsh mountain environment led to its closure in 1921 in favor of a toll road. Today, remnants of the route are preserved in hiking trails and historical markers along the route to Mount Mitchell, including near the Montreat Camp and Conference Center.

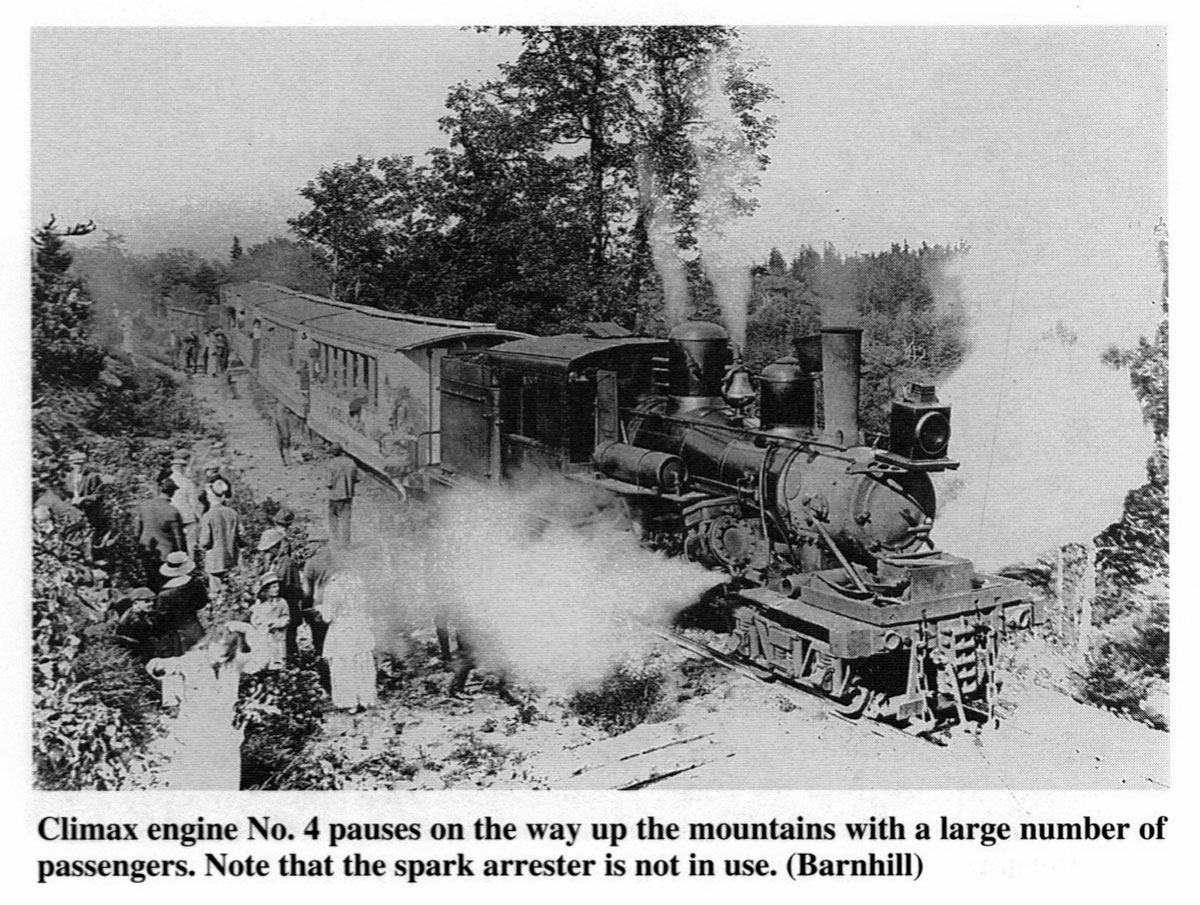

from Mount Mitchell: Its Railroad and Toll Road by Jeff Lovelace / collection

Montreat, NC / Jun 2023 / RWH

Jun 2023 / RWH

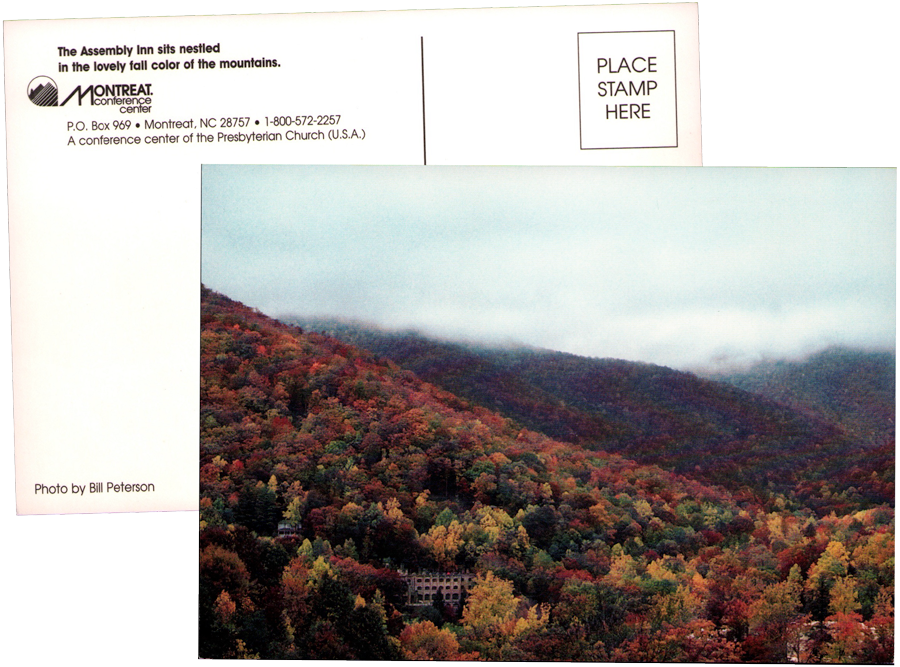

postcard / collection

Click to see the Presbyterian Heritage Center plotted on a Google Maps page

1910 Official Guide map / collection

1910 Official Guide ad / collection

Jun 2023 / RWH

o one who loves railroads and railroading, the story of the development of the Mount Mitchell Railroad is a captivating chapter of the mountain's history. An enormous challenge to reach Eastern America's highest peak by a narrow-gauge railroad was achieved by Dickey & Campbell and Perley & Crockett.

o one who loves railroads and railroading, the story of the development of the Mount Mitchell Railroad is a captivating chapter of the mountain's history. An enormous challenge to reach Eastern America's highest peak by a narrow-gauge railroad was achieved by Dickey & Campbell and Perley & Crockett.

Jeff Lovelace / Mount Mitchell: Its Railroad and Toll Road

Jun 2023 / RWH

Jun 2023 / RWH

Jun 2023 / RWH

Jun 2023 / RWH

Jun 2023 / RWH

Jun 2023 / RWH

Jun 2023 / RWH

Mt. Mitchell Railroad route map / adapted RWH

Jun 2023 / RWH

Jun 2023 / RWH

collection

from Mount Mitchell: Its Railroad and Toll Road by Jeff Lovelace / collection

Feb 2022 / collection

Jun 2023 / RWH

Jun 2023 / RWH

Jun 2023 / RWH

Jun 2023 / RWH

Jun 2023 / RWH

Jun 2023 / RWH

Jun 2023 / RWH

Jun 2023 / RWH

Jun 2023 / RWH

Jun 2023 / RWH

Jun 2023 / RWH

Jun 2023 / RWH

Jun 2023 / RWH

Jun 2023 / RWH

Article

Article

Taking the High Roads

Before the Blue Ridge Parkway paved the way, Mt. Mitchell’s visitors rode storied rail lines and motor routes to the top

May 2014

Today, you can drive a scenic highway almost all the way to the crest of the highest elevation east of the Mississippi. As an old mountain ballad noted, it wasn’t always so easy: “It’s a long hike to old Mt. Mitchell, it’s a long way to go,” the song went. “It’s a long hike to old Mt. Mitchell, the highest peak I know.”

Scaling the 6,683-foot mountain was indeed a hard slog. After all, Elisha Mitchell, who famously documented Mt. Mitchell’s height and posthumously gave his name to it, plunged to his death there during a climb in 1857. But early in the 20th century, commercial explorers created motorized routes that put Mt. Mitchell’s summit increasingly within reach.

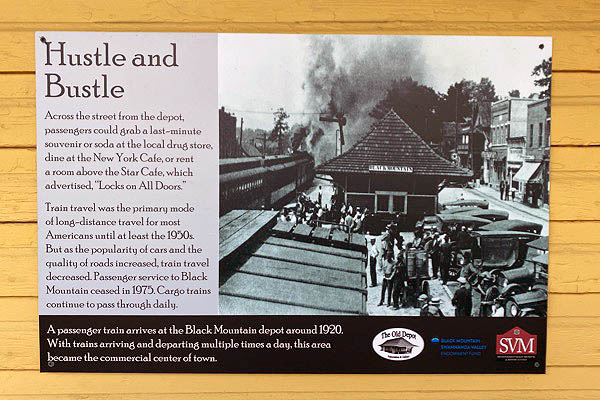

Civic and business leaders in nearby Black Mountain were the biggest early advocates of creating mass transit to the top of the mountain. On the one hand, the desire to build a new tourism base was strong, noted local historian Jeff Lovelace in his 1994 book, Mount Mitchell: Its Railroad and Toll Road. What’s more, he wrote, railroad tycoons and logging companies “wanted to get their hands on the enormous virgin forests in the Black Mountain range.”

In the summer of 1915, both tourists and logging interests took to the rails with the completion of the Mt. Mitchell Railroad, which spanned a winding, 21-mile route from a base in Black Mountain. It arrived at Camp Alice, a mountainside clearing dotted with cabins, tents, and a dining hall, just a quarter-mile trek from the top of Mt. Mitchell. The railroad carried tourists up and down the mountain, and timber on a one-way trip down.

In the summer of 1915, both tourists and logging interests took to the rails with the completion of the Mt. Mitchell Railroad, which spanned a winding, 21-mile route from a base in Black Mountain. It arrived at Camp Alice, a mountainside clearing dotted with cabins, tents, and a dining hall, just a quarter-mile trek from the top of Mt. Mitchell. The railroad carried tourists up and down the mountain, and timber on a one-way trip down.

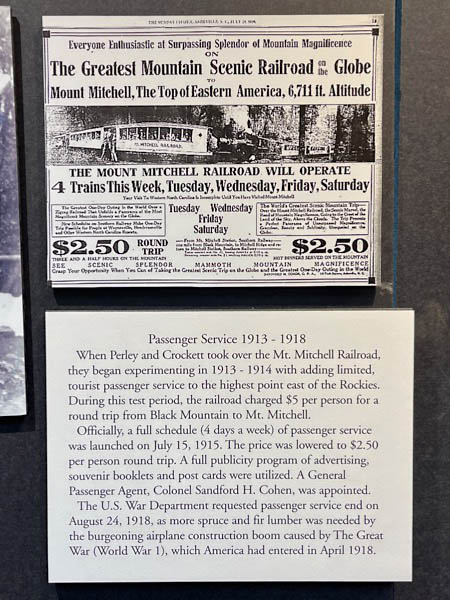

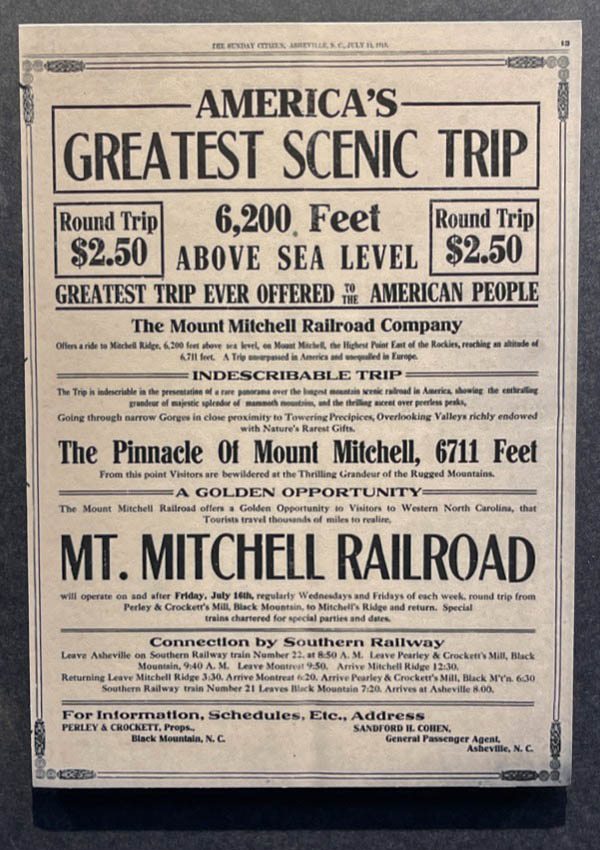

Mt. Mitchell’s lofty views proved a compelling draw. “Highest Railroad East of the Rockies,” one newspaper ad boasted. “A scenic marvel presenting a peerless panorama of mountain magnificence.” In the railroad’s first year alone, some 15,000 sightseers purchased $2.50 round-trip tickets, despite the fact that it was a somewhat taxing jaunt. The ride was three hours to the top, and three and half on the journey downward.

As much as the railroad opened access to Mt. Mitchell, though, it ravaged it. It took only four years for loggers to deforest most of the mountain, and their operations took prerogative in 1919, so much so that passenger trips were canceled. By 1921, there was effectively no wood left to harvest, so the logging trains stopped as well.

By then, Americans were increasingly drawn to a new type of transportation, the rapidly advancing automobile. In 1922, the hastily built Mt. Mitchell Motor Road opened, and caravans of cars streamed up the single-lane bed of rock, dirt, and cinders, on a toll route that mostly paralleled the rail line. A promoter was fond of saying the road was “making the apex of Appalachia accessible.” With dining, lodging, mountain music, and walks among the clouds on offer at the re-invigorated Camp Alice, now just two hours away, it became one of WNC’s ultimate day trips.

So great was the attraction that an entrepreneur soon built another roadway, this one from the western, Yancey County side of the mountain. The Big Tom Wilson Motor Road, opened in 1925, was deeply rooted in Mt. Mitchell’s history. “Big Tom” was the renowned bear hunter and Daniel Boone descendant who found Elisha Mitchell’s body. His grandson, Ewart Wilson, commissioned the 11-mile toll road, which, like its predecessor, built a unique culture around a rough-hewn style of tourism.

Ewart, also a formidable bear hunter, escorted bands of sportsmen up the road. Along the route, at Stepps Gap, he added new facilities to accommodate tourists, including a restaurant, souvenir shop, and small inn. His road wasn’t exactly a joy ride, though. “It went through some of the roughest country you ever saw,” remembers Ewart’s grandson, David Boone, who still lives in the area. “There was a lot of rock and a lot of cliffs to navigate.”

In the late 1930s, the Blue Ridge Parkway opened a modern, paved path to Mt. Mitchell, and the two toll roads closed. Remnants of both are still popular with hikers today, and each fall, the Swannanoa Valley Museum leads a caravan of vehicles up the bumpy bed of the old Mt. Mitchell Motor Road.

Of course, most contemporary visitors favor the Parkway as a means of scaling Mt. Mitchell. According to the N.C. Division of Parks and Recreation, almost a quarter million visitors now take that route each year, following in the hard-won pathways of those who reached for the mountain’s heights long ago.

Jon Elliston / Western North Carolina Magazine

postcard / collection

Right of Way

Right of Way

ven before 1910, residents and businessmen from Black Mountain, North Carolina, were very interested in building a toll road or railroad from Black Mountain to Mount Mitchell. The residents clearly desired a more direct route to the infamous mountain for tourism. Railroad tycoons, however, wanted to get their hands on the enormous virgin forests in the Black Mountain range. The businessmen saw the forest for its resources, and the townspeople wanted Mount Mitchell for sightseeing, fishing, hunting, and picnicking, and to take walks among the clouds.

ven before 1910, residents and businessmen from Black Mountain, North Carolina, were very interested in building a toll road or railroad from Black Mountain to Mount Mitchell. The residents clearly desired a more direct route to the infamous mountain for tourism. Railroad tycoons, however, wanted to get their hands on the enormous virgin forests in the Black Mountain range. The businessmen saw the forest for its resources, and the townspeople wanted Mount Mitchell for sightseeing, fishing, hunting, and picnicking, and to take walks among the clouds.

It was on November 24, 1910, that several Black Mountain residents made an inspection trip of the proposed railroad/motor toll road route, accompanied by an expert engineer. Walking the mountains for about three days, they got an estimate of the cost of the road and saw what obstacles stood in its way. They believed that by crossing the ridges and the high peaks, a feasible gradient could be built. A bond referendum was to be passed, and it was stated that the projected toll road could be built for less than $100,000. The township of Black Mountain hoped to collect enough toll fares to pay for the construction of the road and still have enough left over to start a sinking fund for retiring the road bonds.

Then in 1911, the partnership of C.A. Dickey and J.C. Campbell began to formulate their plans to build a logging railroad which would extend from just east of the town of Black Mountain to a point near the foot of Mount Mitchell. To gain access to much of the proposed railroad property, several right-of-ways had to be obtained. After Dickey and Campbell purchased the timber lines, a preliminary survey was done by John N. Shoolirell and H. Roths, both from Waynesville, N.C.

They spent several weeks in the mountains, inspecting until November 1911. They concluded that the railroad would consist of several switchbacks and would not exceed a grade of five percent. This gradient would be safe for any passengers riding on the proposed line.

Jeff Lovelace / Mount Mitchell: Its Railroad and Toll Road

Black Mountain, NC / Jun 2025 / RWH

Jun 2025 / RWH

Jun 2025 / RWH

Jun 2025 / RWH

Click to see the historical marker location plotted on a Google Maps page

Black Mountain, NC / Jun 2025 / RWH

Black Mountain, NC / Jun 2025 / RWH

Black Mountain, NC / Jun 2025 / RWH

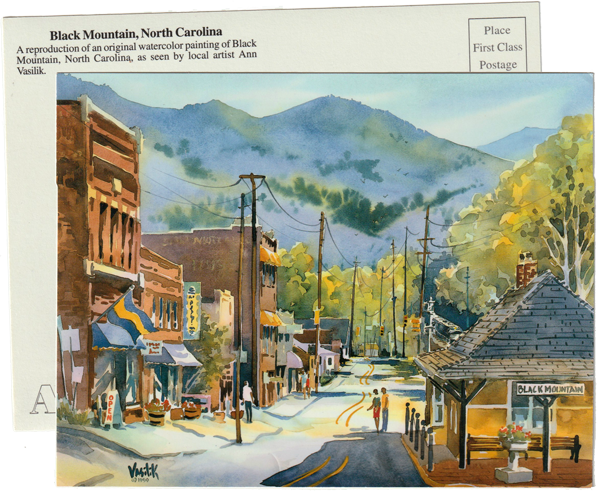

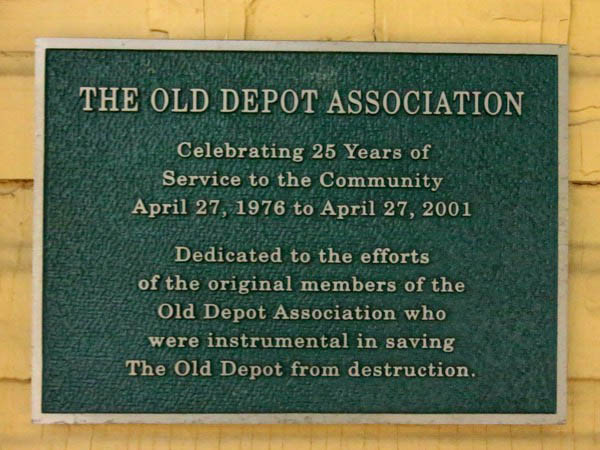

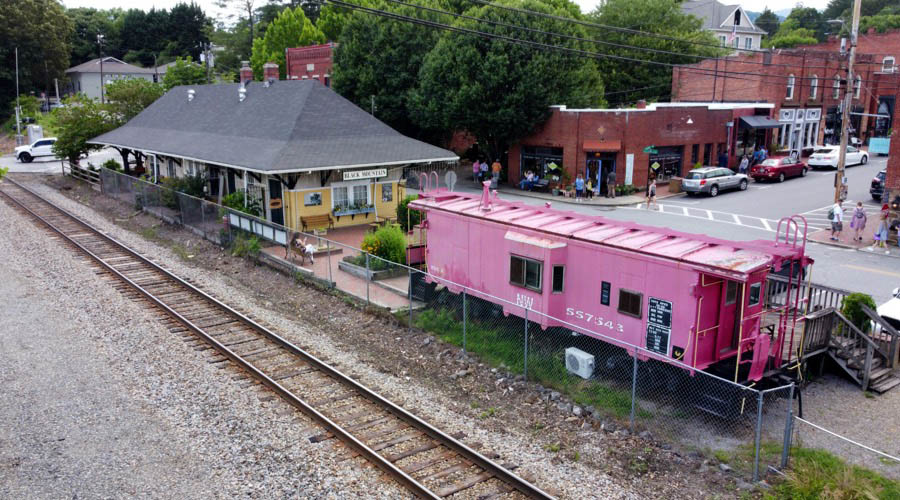

Black Mountain

Black Mountain

postcard / collection

lack Mountain, located 15 miles from Asheville on the eastern edge of Buncombe County, is a quintessential small town, complete with a charming and walkable downtown, a thriving arts and crafts scene, and—at 2,405 feet in elevation—access to incredible outdoor adventure.

Named for a mountain range that towers over the town, Black Mountain became a haven for pioneers in the world of art, painting, music, poetry, and architectural design during the mid-twentieth century. The town was once home to Black Mountain College, one of the most highly-respected and innovative experimental art colleges in the U.S. Today it remains an artist mecca with multiple galleries showcasing some of the region’s best southern Appalachian arts and crafts.

lack Mountain, located 15 miles from Asheville on the eastern edge of Buncombe County, is a quintessential small town, complete with a charming and walkable downtown, a thriving arts and crafts scene, and—at 2,405 feet in elevation—access to incredible outdoor adventure.

Named for a mountain range that towers over the town, Black Mountain became a haven for pioneers in the world of art, painting, music, poetry, and architectural design during the mid-twentieth century. The town was once home to Black Mountain College, one of the most highly-respected and innovative experimental art colleges in the U.S. Today it remains an artist mecca with multiple galleries showcasing some of the region’s best southern Appalachian arts and crafts.

Black Mountain, NC / Apr 1999 / JCH

1910 Official Guide ad / collection

Black Mountain, NC / Nov 2001 / JCH

Click to see the Black Mountain depot area plotted on a Google Maps page

Black Mountain, NC / Nov 2001 / JCH

Black Mountain, NC / Nov 2001 / JCH

Black Mountain, NC / Nov 2001 / JCH

Black Mountain, NC / Jun 2021 / RWH

Black Mountain, NC / Jun 2019 / RWH

Jun 2019 / RWH

postcard / collection

Jun 2021 / RWH

Black Mountain, NC / Jun 2021 / RWH

Black Mountain, NC / Jun 2021 / RWH

Black Mountain, NC / Jun 2021 / RWH

Black Mountain, NC / Jun 2021 / RWH

Jun 2021 / RWH

Black Mountain, NC / Jun 2021 / RWH

Jun 2021 / RWH

Black Mountain, NC / Jun 2021 / RWH

Jun 2021 / RWH

Jun 2021 / RWH

Black Mountain, NC / Jun 2021 / RWH

Jun 2021 / RWH

Jun 2021 / RWH

Black Mountain, NC / Jun 2021 / RWH

Jun 2021 / RWH

Jun 2021 / RWH

Black Mountain, NC / Jun 2021 / RWH

Black Mountain, NC / Jun 2021 / RWH

Black Mountain, NC / Jun 2021 / RWH

Black Mountain, NC / Jun 2021 / RWH

collection

collection

Black Mountain, NC / Jun 2021 / RWH

Black Mountain, NC / Jun 2021 / RWH

Black Mountain, NC / Jun 2021 / RWH

Black Mountain, NC / Jun 2021 / RWH

Black Mountain, NC / Jun 2021 / RWH

See also our complete Old Fort Train Station scrapbook in Preservation

Snapshots

Snapshots

Montreat, NC / Jun 2023 / RWH

Montreat, NC / Jun 2023 / RWH

Montreat, NC / Jun 2025 / RWH

Links / Sources

- Presbyterian Heritage Center at Montreat website

- Taplines Mount Mitchell Railroad page

- North Carolina Railroads Mount Mitchell page

- NCpedia Mount Mitchell Railroad entry

- Jon Elliston — Taking the High Roads — WNC Magazine