|

Arkansas Railroad Museum Steam Locomotives |

collection

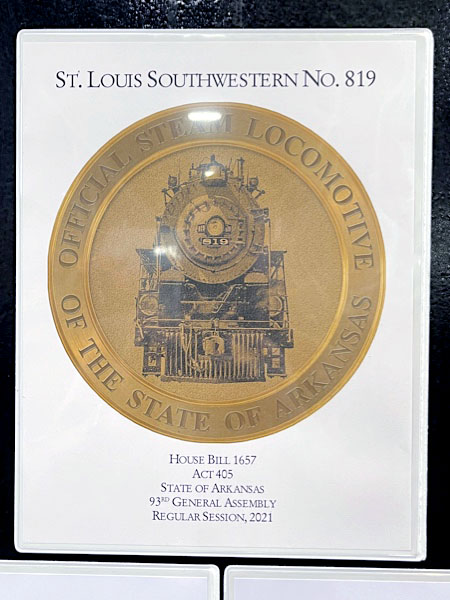

Arkansas' State Steamer

Arkansas' State Steamer

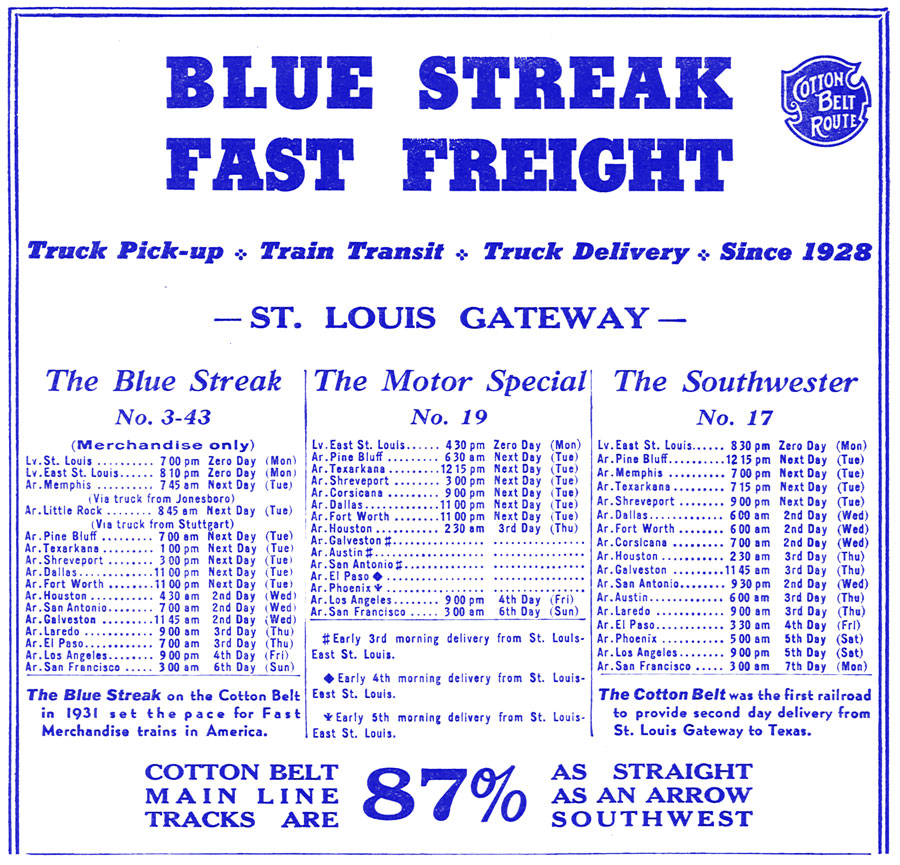

1941 Official Guide ad / collection

UNCOMMON or UNUSUAL locomotive

UNCOMMON or UNUSUAL locomotive

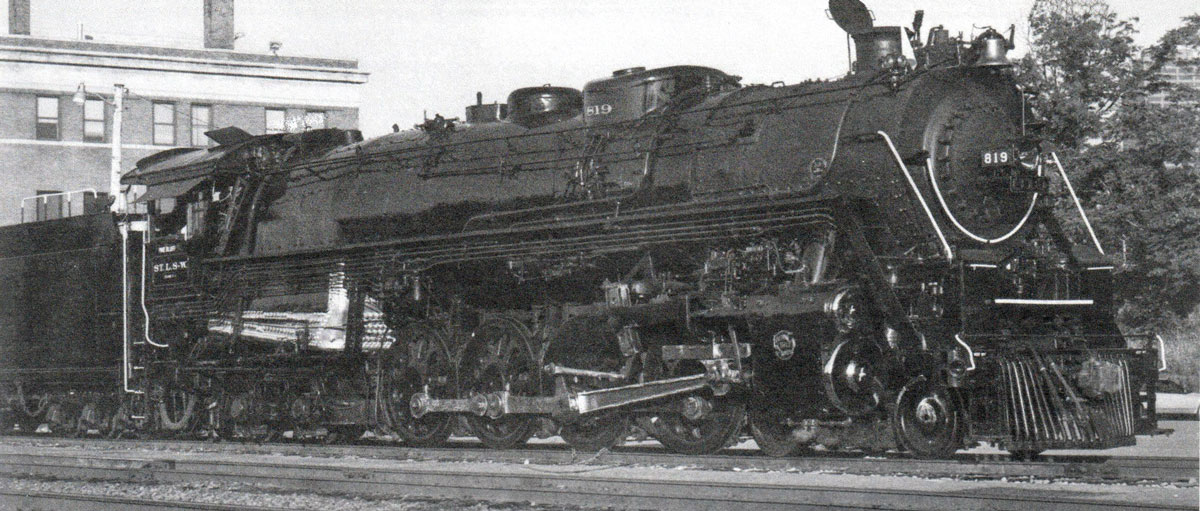

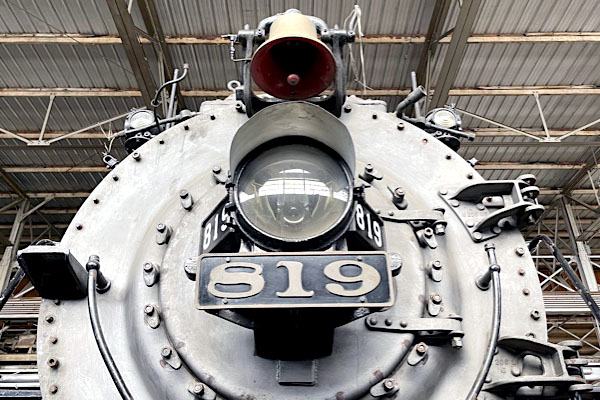

Cotton Belt #819

Saint Louis Southwestern #819

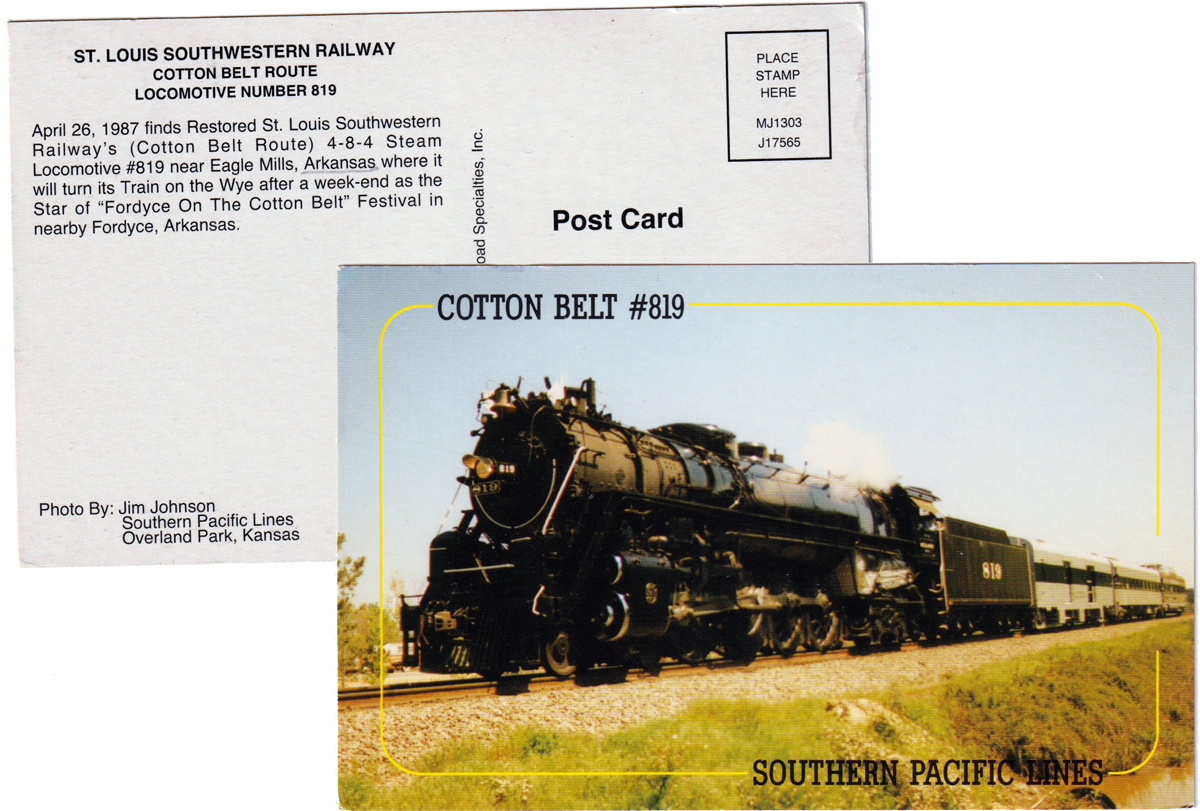

Fordyce, Ar / 1986 / Bill Bailey / Wikipedia Commons

Cotton Belt #819

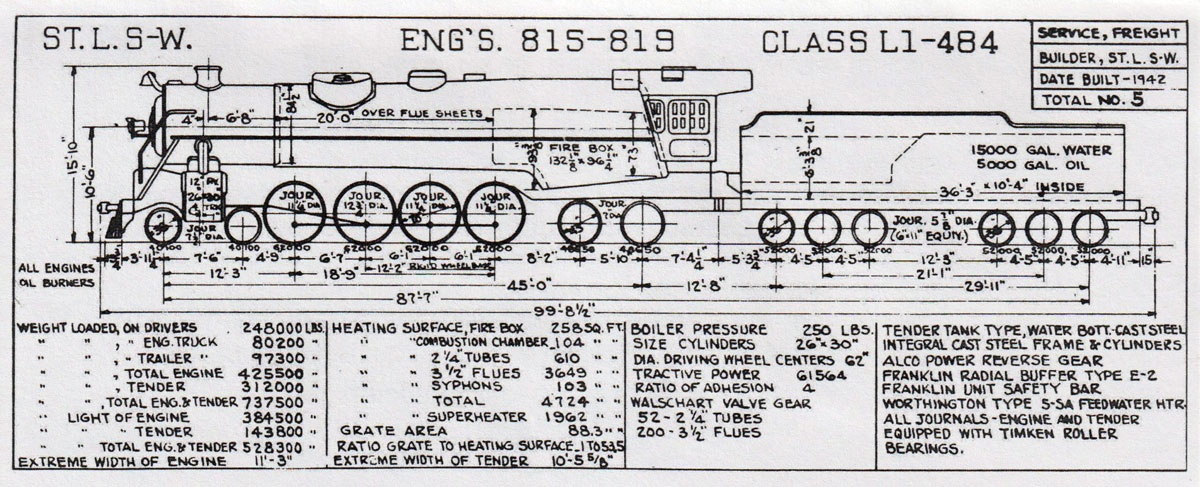

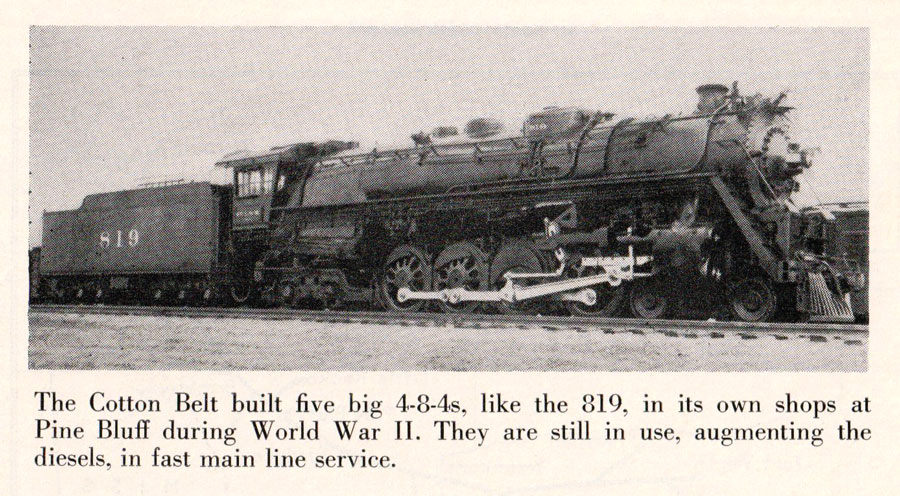

1 of 5 class L-1 built by Pine Bluff

to City of Pine Bluff, 1955

to excursion service, 1983

to Arkansas Railroad Museum

collection

Pine Bluff, Ar / 2016 / Robert Grant

Pine Bluff, Ar / 2016 / RWH

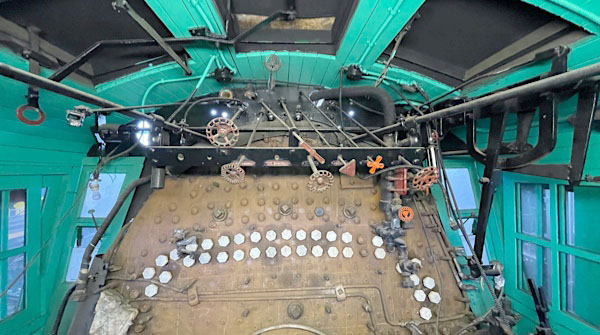

Oct 2022 / RWH

Oct 2022 / RWH

Oct 2022 / RWH

Oct 2022 / RWH

collection

1941 Official Guide ad / collection

RWH

Oct 2022 / RWH

collection

Oct 2022 / RWH

Oct 2022 / RWH

Oct 2022 / RWH

Oct 2022 / RWH

from Handbook of American Railroads - Robert Lewis - 1951 / collection

postcard / collection

Oct 2022 / RWH

Oct 2022 / RWH

Article

Article

Cotton Belt Engine 819

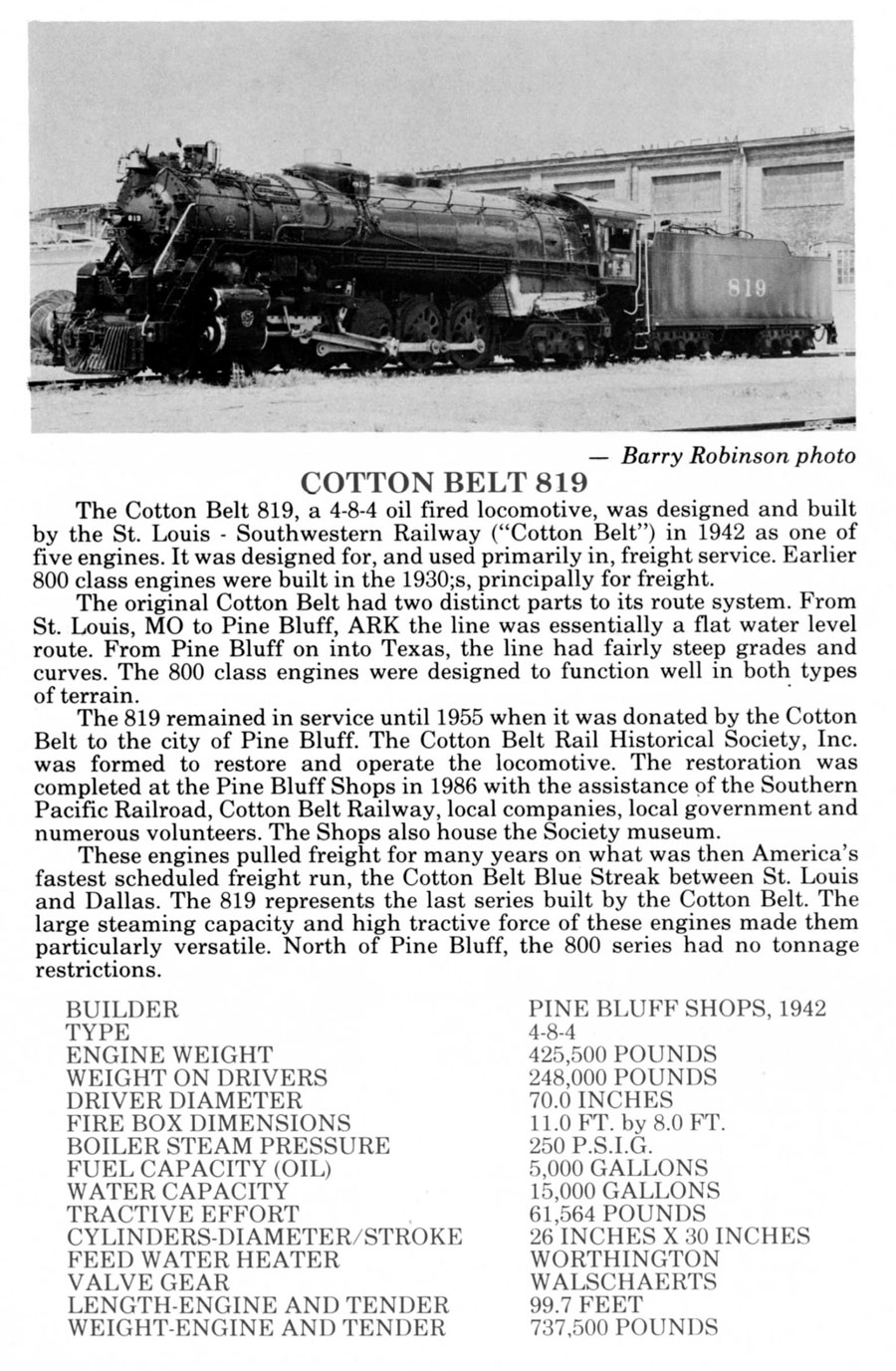

The St. Louis Southwestern #819 4-8-4 steam locomotive, completed in 1943, was the final locomotive constructed by the Cotton Belt's own staff of mechanical engineers, mechanical officers, foremen and workers in the company shops at Pine Bluff, Arkansas. It rolled into service on February 8, 1943, the last locomotive built in Arkansas.

Engine 819, a Northern-type oil burner, traveled more than 804,000 miles during its ten years of service. On July 19, 1955 Cotton Belt's President H. J. McKenzie donated Engine 819 to the City of Pine Bluff for the sum of $1. The engine had been in dead storage in Tyler. Locomotives 815 through 818 were scrapped between 1955 and 1957.

The problem of getting the locomotive moved to a display area in Oakland Park was solved when Cotton Belt agreed to lend materials for a temporary spur. Cotton Belt and Missouri Pacific employees contributed the labor in building the spur and moving the historic locomotive and its tender.

The problem of getting the locomotive moved to a display area in Oakland Park was solved when Cotton Belt agreed to lend materials for a temporary spur. Cotton Belt and Missouri Pacific employees contributed the labor in building the spur and moving the historic locomotive and its tender.

I have a strong connection with the move of #819. My uncle, Doyle S. Gibson, was a civil engineer working for the Cotton Belt at the time, and was involved in the design of the logistics involved in moving the locomotive. I visited him in Pine Bluff at the time, and recall the work he did in transitioning the engine to the park. Doyle was also involved in building the Pine Bluff Gravity Yard.

St. Louis Southwestern (SSW) 4-8-8 Steam Engine #819 The engine remained on static display for nearly 30 years, but bore the brunt of neglect, rust, graffiti, and vandals who stole brass parts.

In December of 1983 a group of Cotton Belt employees, volunteers, rail fans and rail historical groups placed Engine 819 back on Cotton Belt rails for the first time in nearly three decades. The engine was moved from its former display back to the site of its construction 40 years earlier. Volunteers spent three years and 37,000 hours of time, and used $140,000 in donated materials, in restoring the engine. Bill Bailey, a civil engineer from Little Rock, presided over the restoration project.

On April 6, 1986, Engine 819 moved out of the Cotton Belt Route's yard at Pine Bluff marking the first time it had moved under its own power since 1953. For the next 15 years, the locomotive traveled on numerous excursions.

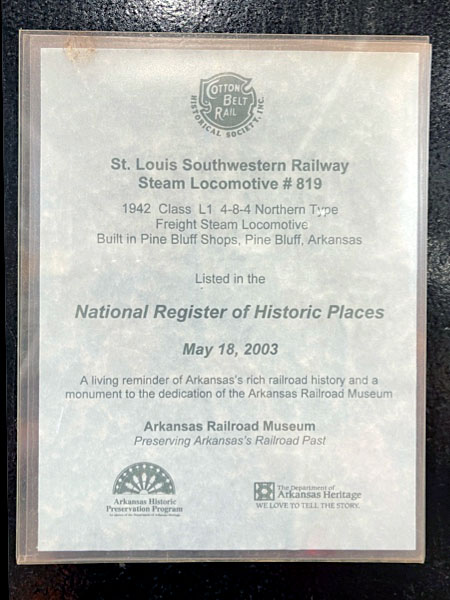

The mighty engine was placed on the National Register of Historic Places on May 18, 2003.

The mighty engine was placed on the National Register of Historic Places on May 18, 2003.

The restored Cotton Belt Engine #819 visited Tyler, Texas in 1988 (see photo below). More than 1,000 Tyler residents greeted the historic steam engine. The arrival of this special nine-car train in Tyler coincided with ceremonies donating the Cotton Belt passenger depot to the City of Tyler.

For the first time in more than 33 years, the 4-8-4 Northern-style oil burner made the trip from Pine Bluff, Arkansas, to Tyler, the two traditional capitals of the St. Louis Southwestern Railway.

The round-trip spanned 560 miles. Thousands of spectators lined the route, including scores of children who were given the opportunity to see part of railroad history roll down the tracks. Nearly 1,500 passengers rode the train at some point during the trip.

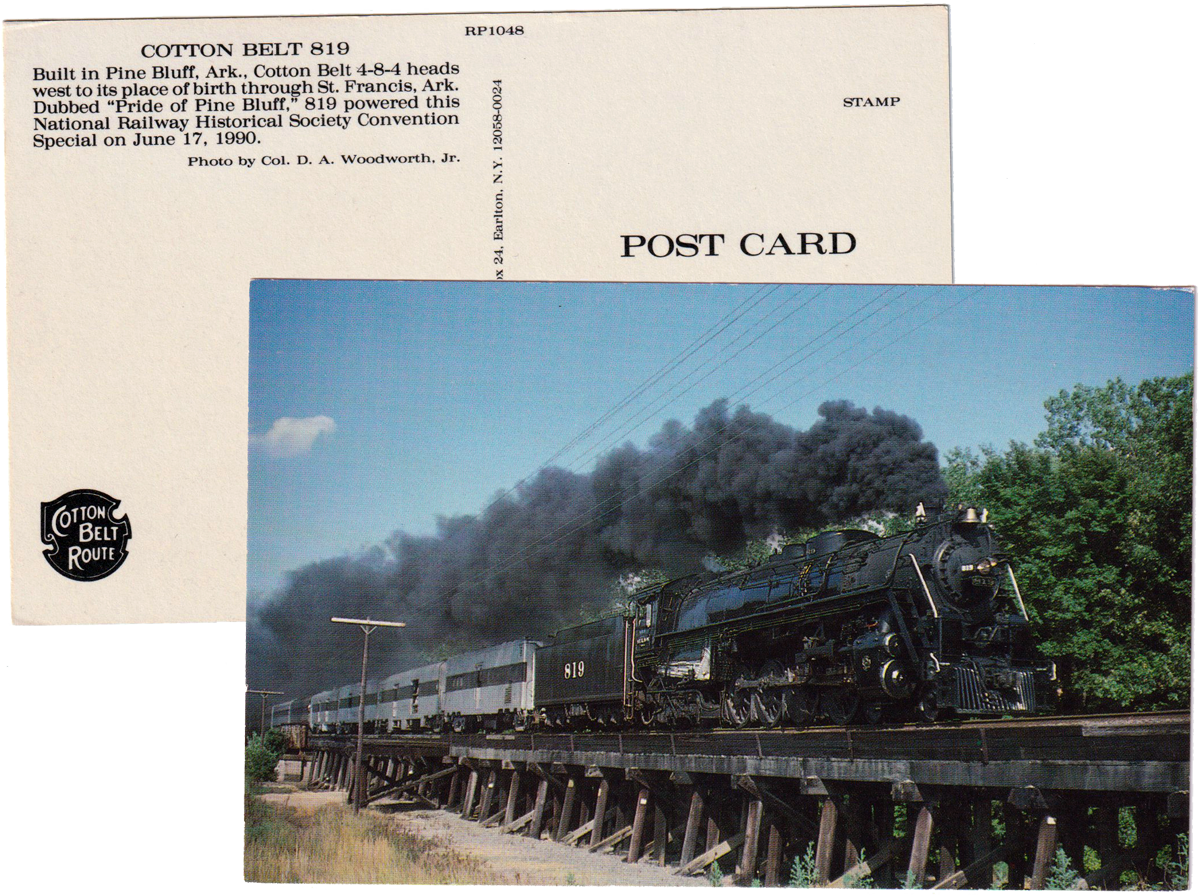

Engine 819 made another trip to Tyler, arriving on October 16, 1993 for the Texas Rose Festival, pulling a tender and 14 passenger cars. It appeared in Little Rock in June 1986 for the Arkansas Sesquicentennial, and in St. Louis in 1990 for the National Rail Historical Society's annual convention.

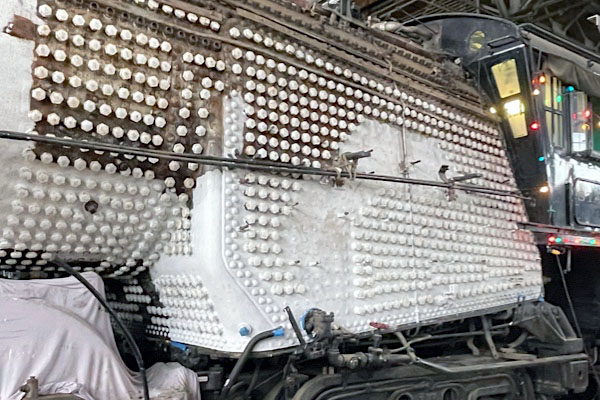

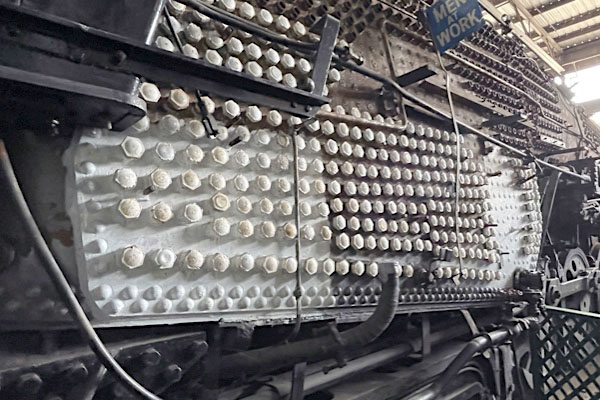

Today, in 2022, the mighty 819 is maintained and being restored again at the Arkansas Railway Museum in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, by the Cotton Belt Rail Historical Society. The Museum is housed in what was once the Cotton Belt's locomotive fabrication building.

Oct 2022 / RWH

Oct 2022 / RWH

Oct 2022 / RWH

Oct 2022 / RWH

Oct 2022 / RWH

extra Class L-1 tender / Oct 2022 / RWH

1990 NRHS Convention Special

1990 NRHS Convention Special

from 1990 NRHS Annual Convention information / collection

postcard / collection

The St. Louis Steam Gathering

The three of us had been to shoot trains on it once before, and we decided that we would start our chase of the Cotton Belt Star there. The train was en route to the convention, having left Pine Bluff, Arkansas, the day before with restored steam engine #819 pulling the train.

A fair sized crowd was gathering about the time we pulled up. I took note of one of the faces in the crowd; Jim Boyd, then the editor of Railfan & Railroad magazine. More and more people arrived as the train’s scheduled departure from Scott City, Missouri, neared, until the area seemed littered with bodies, cameras, tripods and parked cars.

Departure time came and went, and loud conversations quieted as people listened for the first sign of #819’s distant whistle. Nothing. A barge passed on the river, sounding for the world like an approaching freight train.

Then suddenly, there it was. A faint, melodic sound of a baritone chime whistle. Conversations ceased. Louder, the distant whistle was heard again; followed by the appearance of a light haze of smoke over the trees on the Missouri side of the river. Momentarily the black front of the locomotive rounded the curve on the approach to the bridge, the shimmering glow of the headlight the Cyclops’s eye.

Then suddenly, there it was. A faint, melodic sound of a baritone chime whistle. Conversations ceased. Louder, the distant whistle was heard again; followed by the appearance of a light haze of smoke over the trees on the Missouri side of the river. Momentarily the black front of the locomotive rounded the curve on the approach to the bridge, the shimmering glow of the headlight the Cyclops’s eye.

Now on the bridge #819’s engineer blew several times on the whistle, more for the benefit of members of a track gang working on the other track than for the crowd of fans waiting at the end of the bridge. Another series of blasts on the whistle and the engine emerged from the steel truss work of the bridge, taking it easy in compliance with the speed limit over the bridge.

As the rear of the train passed, the mad dash began. The crowd of railfans dashed for their cars. Camera gear was thrown into trunks and back seats. Cars that weren’t facing out to begin with jockeyed for position to get out. The three of us crossed back over the track to Rob’s waiting car and joined the pack.

Now the idea on a chase like this is to leap frog the train as many times as you can to get as many shots in as many locations as possible. The speed limit for a passenger train up the Chester Subdivision of the Union Pacific is seventy miles per hour. We were well behind the train, which by the time we got back to route 3 and turned north was rapidly accelerating to its maximum speed. It was off to the races.

And a race it was. Suddenly Illinois Route 3 became the track for a true stock car race. No fancy cars, pit crews or crew bosses radioing from a center stand. No, rather this race consisted of around thirty off the shelf cars, trucks and vans racing north at eighty miles per hour. Might as well have been a NASCAR race as cars jockeyed for position and passed one another. A few at the front trying to get alongside the locomotive to get the coveted pacing footage on their video cameras while the rest of us tried passing them to get ahead of the train.

Northbound we went. At McClure, the train was just a cloud of smoke in the distance. To this day I kind of pity the little old lady south of Reynoldsville, driving along at 45 miles an hour only to find herself being overtaken by the Indy 500. By Reynoldsville we could see the rear of the train. The pace slowed as the lead cars caught the locomotive and slowed to match its speed. By Ware we had caught the rear of the train, and we were just behind the locomotive by Wolf Lake.

Northbound we went. At McClure, the train was just a cloud of smoke in the distance. To this day I kind of pity the little old lady south of Reynoldsville, driving along at 45 miles an hour only to find herself being overtaken by the Indy 500. By Reynoldsville we could see the rear of the train. The pace slowed as the lead cars caught the locomotive and slowed to match its speed. By Ware we had caught the rear of the train, and we were just behind the locomotive by Wolf Lake.

For the last fifteen miles or so the road had paralleled the track, and we only made headway a few cars at a time as cars at the front of the pack passed the pace vehicles blocking the way. Just north of Wolf Lake the track and highway diverge. It was back to the races. 80 miles an hour we ran, headed for Gorham. I kept an eye for smoke behind us as we turned off of route 3 and onto the road into downtown Gorham. We skidded to a stop near the old railroad office and grabbed our gear, setting up for our shot as quickly as we could. And then nothing happened.

Five minutes. No sign of it. Then ten. Finally we heard a couple of fans talking nearby.

“The detector at milepost 92 got ‘im.”

That explained it. Every twenty miles or so is a device alongside the track which checks for overheated axle bearings. Long ago this task was performed by local station agents who would watch trains pass their stations all hours of the day and night. Those little local operations are but a memory now, with the automated trackside detectors doing the job.

Only problem is that with a steam engine a detector can’t tell the difference between a overheated bearing, the cylinders which are heated by superheated steam and the locomotive’s firebox. When the detector misread the cylinders or firebox (or both) as a hot bearing, the train crew was mandated by rule to stop and inspect the non-existent problem.

“Well, that explains what hole he fell into,” I said.

Before long a flock of fans pulled up, and moments later we could hear the sound of the locomotive’s exhaust in the distance. A billowing cloud of thick, black smoke appeared in the distance as the train rounded the curve south of town. Moving at a pace of better than a mile a minute, the train bore down on us with its baritone chime whistle sounding its warning for the one crossing in town. In a flash it was gone, a dancing red taillight in a haze of smoke receding into the distance.

Mary Rae McPherson / Along the Rails Blog

Oct 2022 / RWH

Oct 2022 / RWH

Oct 2022 / RWH

Oct 2022 / RWH

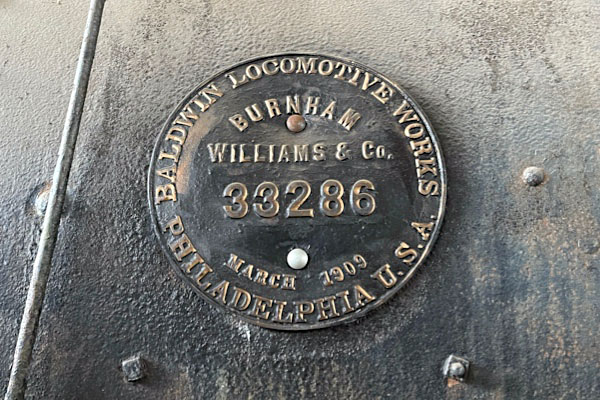

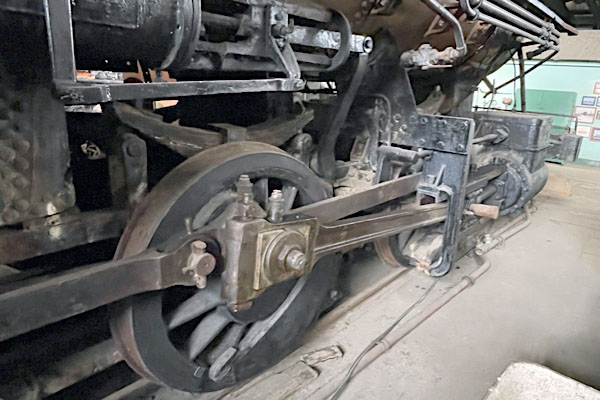

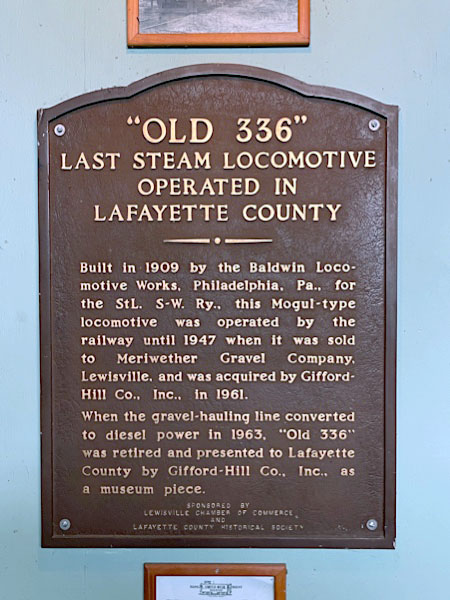

#336

1910 Official Guide ad / collection

Saint Louis Southwestern #336

Saint Louis Southwestern #336

Pine Bluff, Ar / Oct 2022 / RWH

Cotton Belt #336

to Meriweather Gravel Co, 1947

to Gifford-Hill Company

to display Lewisville AR, 1963

to Arkansas Railroad Museum

Oct 2022 / RWH

Oct 2022 / RWH

Oct 2022 / RWH

Oct 2022 / RWH

Oct 2022 / RWH

Oct 2022 / RWH

Oct 2022 / RWH

Oct 2022 / RWH

Oct 2022 / RWH

Oct 2022 / RWH

Pine Bluff, Ar / 2016 / Robert Grant

Links / Sources

- Wikipedia article for Saint Louis Southwestern #819

- Robert Grant's Arkansas Railroad Museum page