|

Amtrak Great Stations Cincinnati, Ohio |

Cincinnati, Oh / May 2024 / RWH

Cincinnati Union Terminal

incinnati Union Terminal, one of America’s great Art Deco rail stations, was completed in 1933 and covers about 500,000 square feet. Its principal architects were Alfred T. Fellheimer and Steward Wagner, with architects Paul Phillippe Cret and Roland Wank brought in as design consultants. New York-based Fellheimer and Wagner were well known by the 1920s for their work on train stations, which included structures in Erie, Pa., South Bend, Ind., Buffalo, N.Y., and Greensboro, N.C.

incinnati Union Terminal, one of America’s great Art Deco rail stations, was completed in 1933 and covers about 500,000 square feet. Its principal architects were Alfred T. Fellheimer and Steward Wagner, with architects Paul Phillippe Cret and Roland Wank brought in as design consultants. New York-based Fellheimer and Wagner were well known by the 1920s for their work on train stations, which included structures in Erie, Pa., South Bend, Ind., Buffalo, N.Y., and Greensboro, N.C.

In Cincinnati, their famed creation remains a symbol of the railroads’ power and glory in the first half of the 20th century. However, Cret was largely responsible for the building’s signature style, and he is often credited as the building’s architect. Its ten-story, half-domed limestone and glass main entrance hall was the only half dome in the Western Hemisphere and the largest in existence when it was constructed (today it is the second-largest in the world).

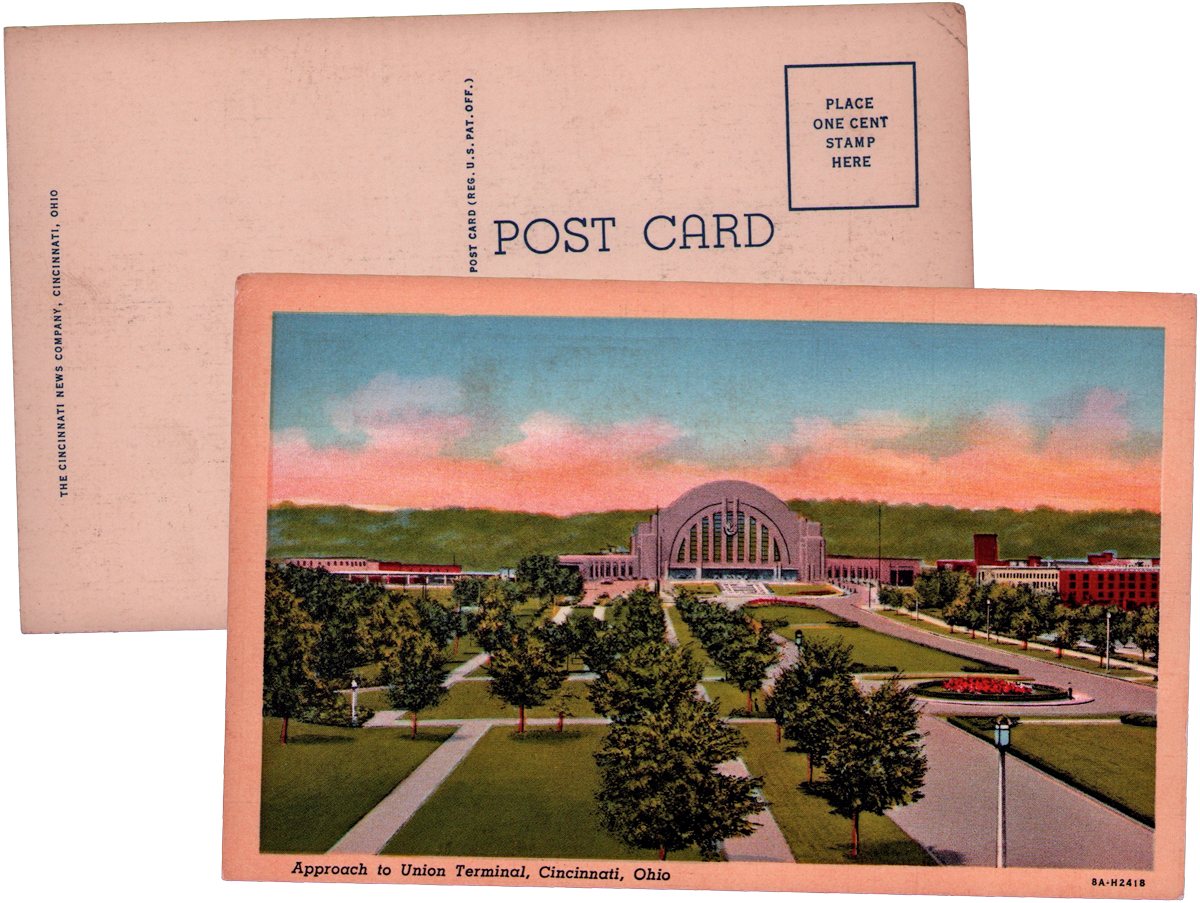

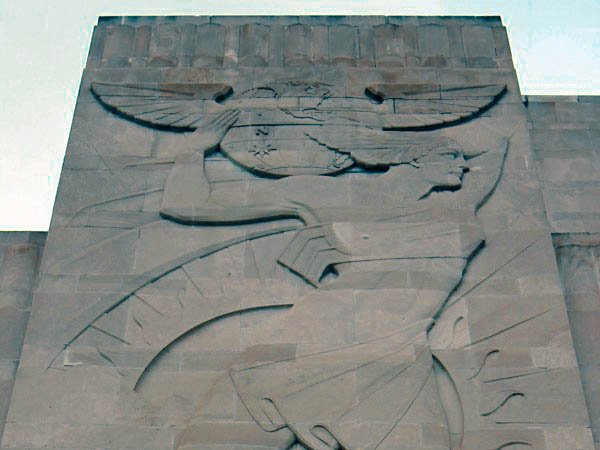

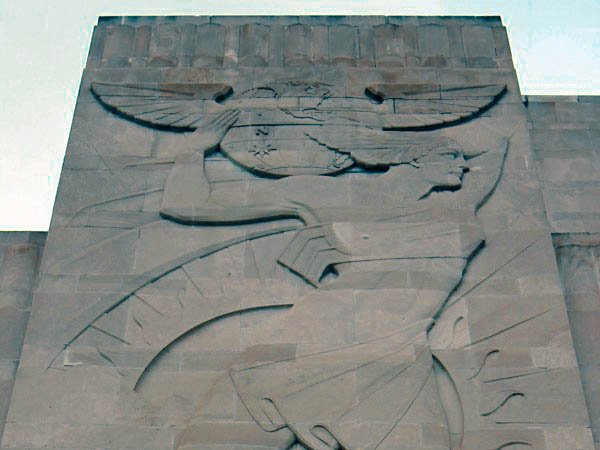

Standing one mile north of the center of Cincinnati, the main facade faces east over a quarter-mile plaza on what was once Lincoln Park. Visitors are greeted by an illuminated fountain with cascade and pool. The dome is flanked on either side by curving wings, and on either side of the main entry doors, Maxfield Keck’s bas-reliefs depicting “Transportation” and “Commerce” keep watch.

Standing one mile north of the center of Cincinnati, the main facade faces east over a quarter-mile plaza on what was once Lincoln Park. Visitors are greeted by an illuminated fountain with cascade and pool. The dome is flanked on either side by curving wings, and on either side of the main entry doors, Maxfield Keck’s bas-reliefs depicting “Transportation” and “Commerce” keep watch.

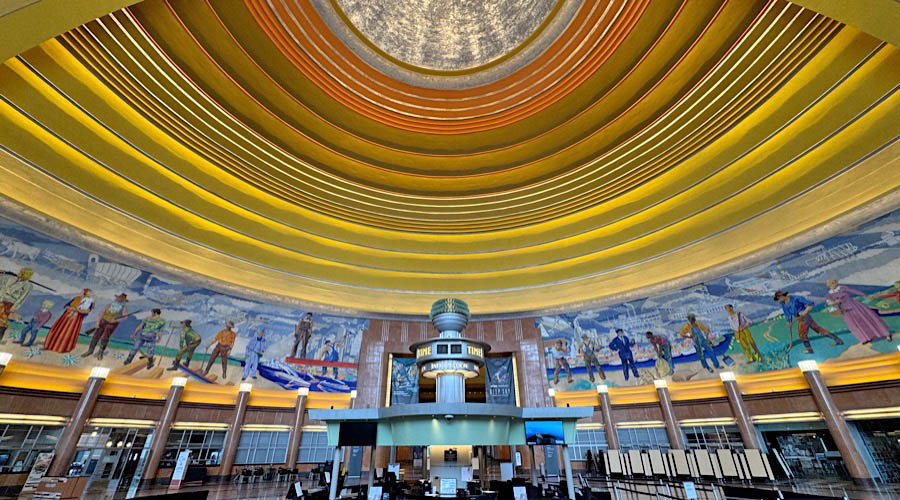

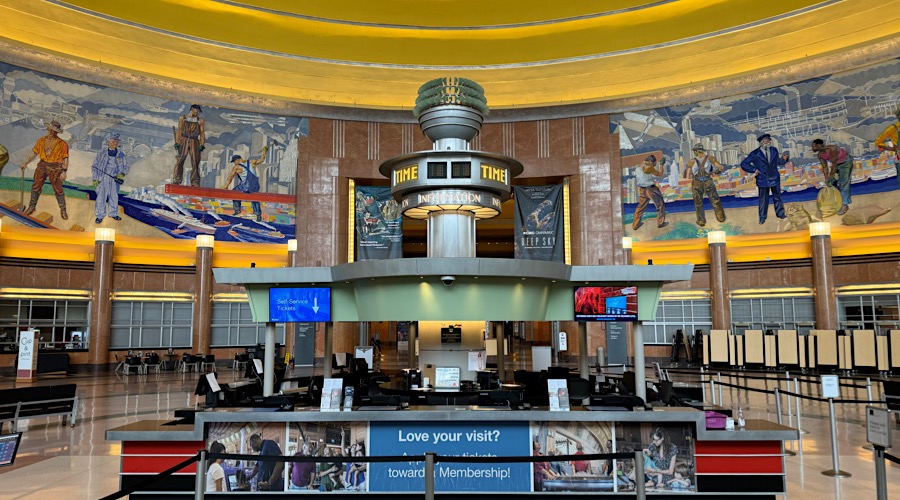

German-born artist Winold Reiss designed and created two 22-foot high by 110-foot long color mosaic murals depicting the history of Cincinnati for the entry rotunda interior, two murals for the baggage lobby, two murals for the departing and arriving train boards, 14 smaller murals for the original train concourse representing local industries and a large world map mural located at the rear of the concourse. Reiss spent nearly two years completing these works.

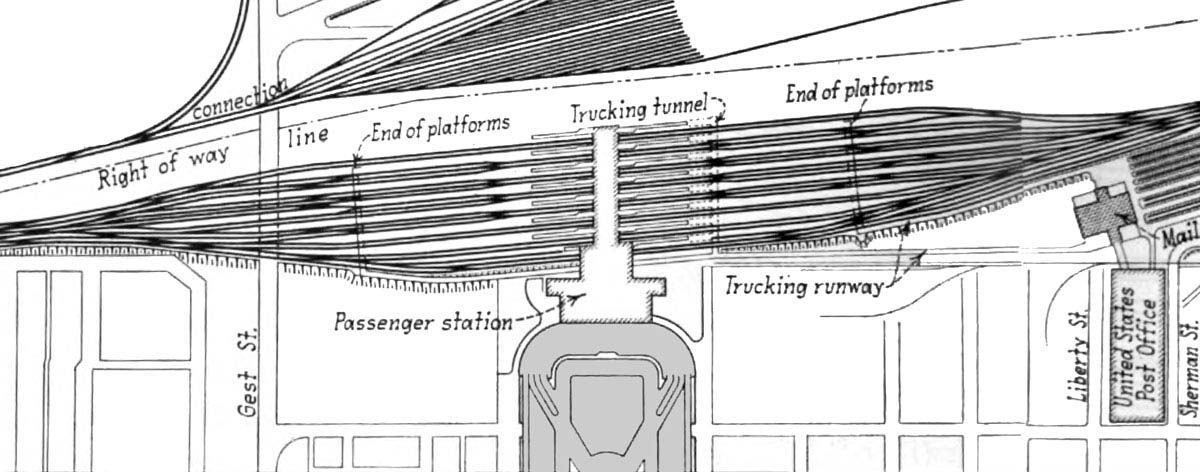

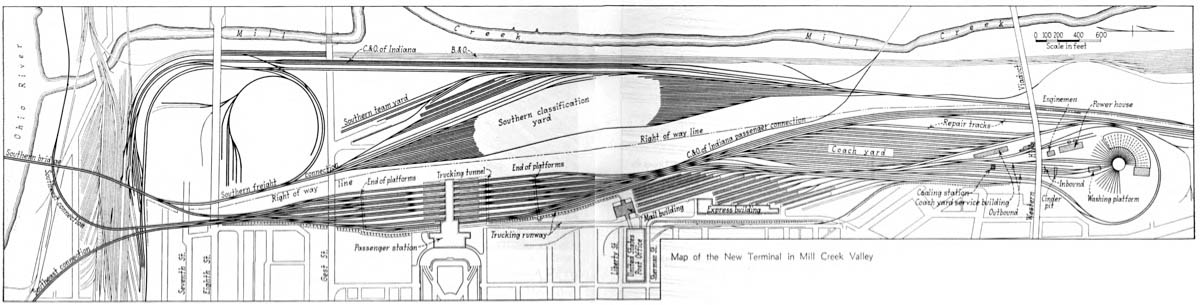

As a major center of railroad traffic in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and an interchange point between the Northeastern and Midwestern states, Cincinnati had no fewer than five downtown passenger stations. As early as the 1890s, the railroads began negotiations to create a union station to consolidate and simplify passenger traffic; however, it would take until 1928 for the seven railroads and the city to come to agreement, after intense lobbying led by Phillip Carey Company President George Crabbs. The seven railroads involved in the agreements were the Baltimore and Ohio; Chesapeake and Ohio; Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago and St. Louis (“Big Four”); Louisville and Nashville; Norfolk and Western; Pennsylvania; and Southern.

Construction began in 1928 with considerable site preparation and grading of a portion of the Mill Creek flood plain on which the terminal was to stand, under the auspices of the newly-formed Union Terminal Company. The terminal building itself was begun in 1931 and the station opened on March 31, 1933. The total cost of the project was $41.5 million.

Construction began in 1928 with considerable site preparation and grading of a portion of the Mill Creek flood plain on which the terminal was to stand, under the auspices of the newly-formed Union Terminal Company. The terminal building itself was begun in 1931 and the station opened on March 31, 1933. The total cost of the project was $41.5 million.

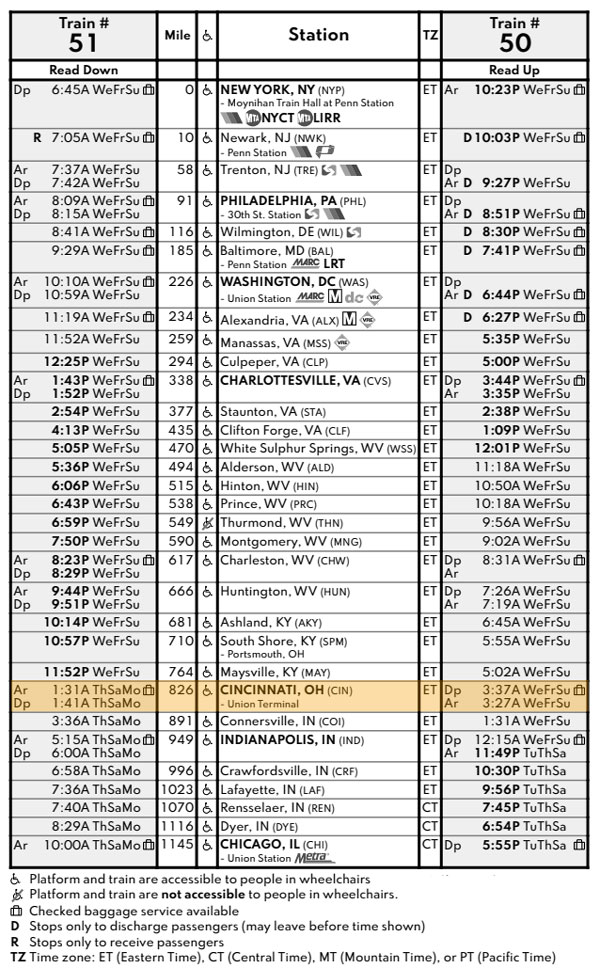

During its heyday, Union Terminal saw 216 trains per day. While it had a brief revival in the 1940s because of World War II, it began to decline in the 1950s. By the time Amtrak began operations in 1971, service was reduced to just two trains a day, the George Washington / James Whitcomb Riley (Washington/Newport News – Chicago). The terminal was abandoned for transportation purposes in 1972 in favor of a much smaller passenger rail station built by Amtrak on the city’s riverfront (now demolished).

In the 1970s, adaptive reuse became an option due to the expense of tearing down such an immense structure. Union Terminal was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1972 and declared a National Historic Landmark in 1977. By 1975 the city had purchased the building and sought to lease it. Within a few years, the Joseph Skilken Organization reopened the terminal as an entertainment and shopping complex, “Land of OZ,” investing more than $20 million for renovations, restaurants, a bowling alley and a roller-skating rink as well as shops. Although this venture began with 40 tenants at its 1978 opening, a recession saw them reduced to 21 by 1982.

In the 1970s, adaptive reuse became an option due to the expense of tearing down such an immense structure. Union Terminal was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1972 and declared a National Historic Landmark in 1977. By 1975 the city had purchased the building and sought to lease it. Within a few years, the Joseph Skilken Organization reopened the terminal as an entertainment and shopping complex, “Land of OZ,” investing more than $20 million for renovations, restaurants, a bowling alley and a roller-skating rink as well as shops. Although this venture began with 40 tenants at its 1978 opening, a recession saw them reduced to 21 by 1982.

The terminal stood empty for several years after the closing of the Land of OZ project. In May 1986, efforts led to a bond levy to save the terminal from demolition and transform it into the Cincinnati Museum Center (CMC). Cincinnati’s then-Mayor Jerry Springer was a major proponent of this transformation. The new center opened in 1990, taking advantage of the terminal’s vast spaces, and now is home to half a dozen museum organizations.

Renovations also allowed the return of Amtrak service to the building – via the Cardinal – on July 29, 1991. The state of Ohio and the city of Cincinnati contributed to this restoration with grants of $8 million and $3 million, respectively; and more than 3,000 individuals, corporations and organizations contributed as well. Since its 1990 reopening, the terminal has attracted more than one million visitors each year.

Renovations also allowed the return of Amtrak service to the building – via the Cardinal – on July 29, 1991. The state of Ohio and the city of Cincinnati contributed to this restoration with grants of $8 million and $3 million, respectively; and more than 3,000 individuals, corporations and organizations contributed as well. Since its 1990 reopening, the terminal has attracted more than one million visitors each year.

In 2008, Union Terminal celebrated its 75th birthday with a month-long calendar of festivities, culminating with a tour of the terminal as it was in the 1940s. In November 2014, the voters of Hamilton County, which includes the city of Cincinnati, overwhelmingly passed Issue 8, a measure to increase the county’s sales tax by one-quarter of one percent over five years. The funding—estimated at nearly $176 million—was dedicated to the rehabilitation of Union Terminal.

A two-and-a-half-year rehabilitation and improvement project, estimated to cost approximately $228 million, began in July 2016 and concluded in November 2018.

Highlights of the rehabilitation include updated mechanical, electrical, heating and air conditioning systems; completion of a new brick face on the rear of the building, where the concourse originally connected with the main building, that is more structurally sound; repointing of the mortar on the exterior to ensure the terminal envelope is watertight; cleaning of the more than 53,000 terracotta tiles lining the interiors of the ramp structures on either side of the Main Hall; and cleaning and restoration or reproduction of nearly 700 historic light fixtures, including outfitting with more energy efficient LED lights.

A two-and-a-half-year rehabilitation and improvement project, estimated to cost approximately $228 million, began in July 2016 and concluded in November 2018.

Highlights of the rehabilitation include updated mechanical, electrical, heating and air conditioning systems; completion of a new brick face on the rear of the building, where the concourse originally connected with the main building, that is more structurally sound; repointing of the mortar on the exterior to ensure the terminal envelope is watertight; cleaning of the more than 53,000 terracotta tiles lining the interiors of the ramp structures on either side of the Main Hall; and cleaning and restoration or reproduction of nearly 700 historic light fixtures, including outfitting with more energy efficient LED lights.

Cincinnati, Oh / May 2024 / RWH

Click to see the Cincinnati Union Terminal plotted on a Google Maps page

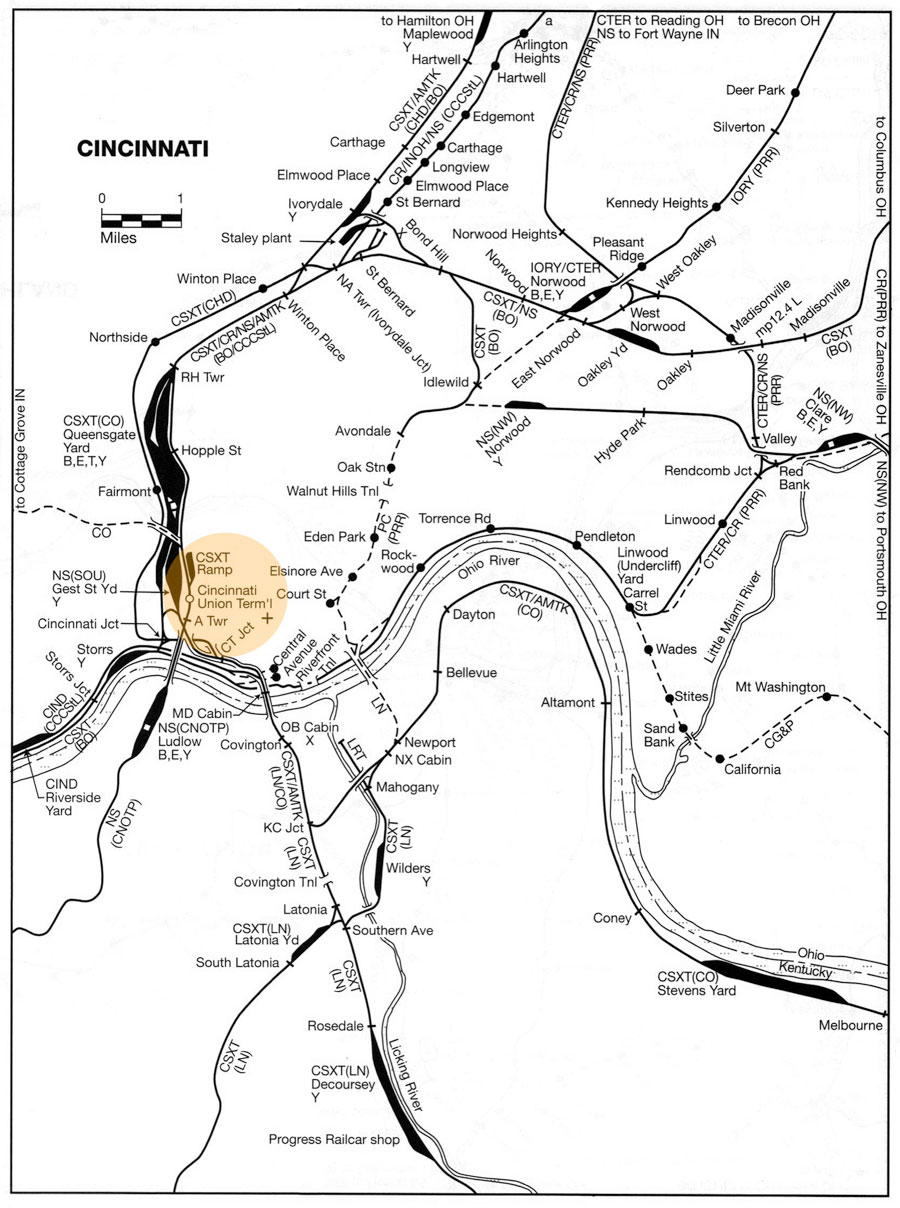

Rail Passengers Association / adapted RWH

collection

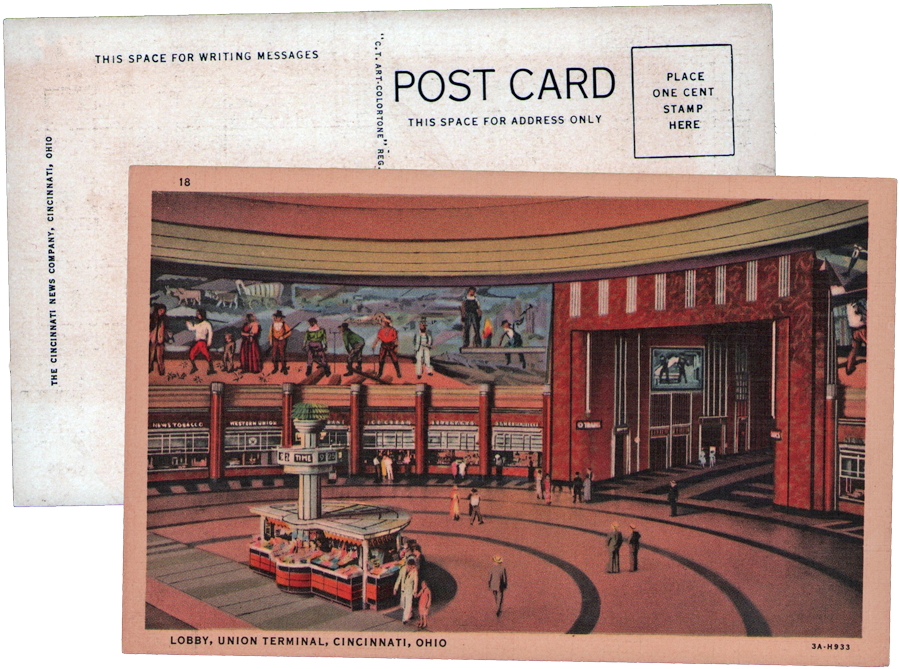

postcard / collection

1937 terminal trackage / collection

Cincinnati

- name:Cincinnati Union Terminal

- station code:CIN

- location:1301 Western Avenue, Cincinnati

- owner:City of Cincinnati

- operators:Amtrak, SORTA

- platforms:1 side platform (originally 8)

- tracks:2 tracks (originally 16)

- opened:1933 (replaced 5 stations)

- style:Art Deco

- architect:Fellheimer & Wagner

- rebuilt:2016-18

- Nat Reg Historic Places:1972

- notes:

- until 1991, Amtrak stopped at a small urban station; Union Terminal now includes Cincinnati Museum Center

- routes:

- Cardinal

RWH

area rail map / adapted RWH

Google Maps

See also our complete Amtrak Cardinal Route Scrapbook in Mainlines

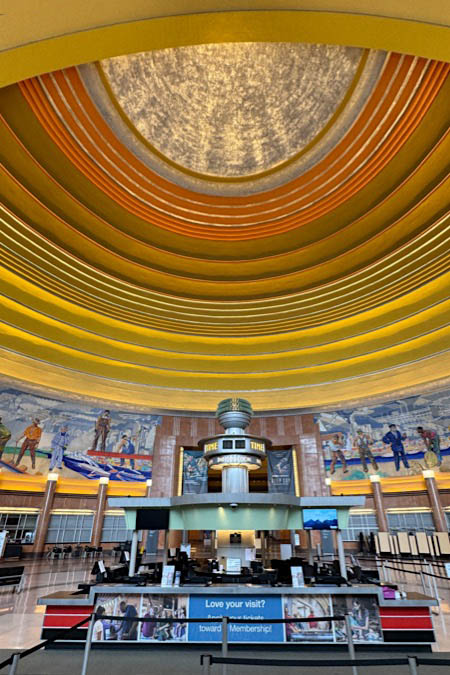

Cincinnati, Oh / May 2024 / RWH

Cincinnati, Oh / May 2024 / RWH

postcard / collection

Cincinnati, Oh / May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

The station building was designed by the firm Fellheimer & Wagner, and is considered the firm's magnum opus. Fellheimer was known for designing train stations; he was lead architect for Grand Central Terminal (1903–1913). The large and busy firm gave the project design to Roland A. Wank, a younger employee.

The station building was designed by the firm Fellheimer & Wagner, and is considered the firm's magnum opus. Fellheimer was known for designing train stations; he was lead architect for Grand Central Terminal (1903–1913). The large and busy firm gave the project design to Roland A. Wank, a younger employee.

Wank's original plan was traditional and featured Gothic architecture: large arches, vaulted ceilings, and conventional benches in long rows. In 1930, while initial construction took place, the terminal company persuaded the architects to hire Paul Philippe Cret as a design consultant. In 1931–32, Cret altered the design aesthetic: thereafter, the terminal and its supporting buildings used modern architecture (later known as Art Deco), even in places not visible or open to the public. The revised designs were approved as cheaper than the intricate Gothic designs, and more cheerful and stimulating with their colorful interiors than previous designs.

Union Terminal / 1947 / Wikipedia

collection

May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

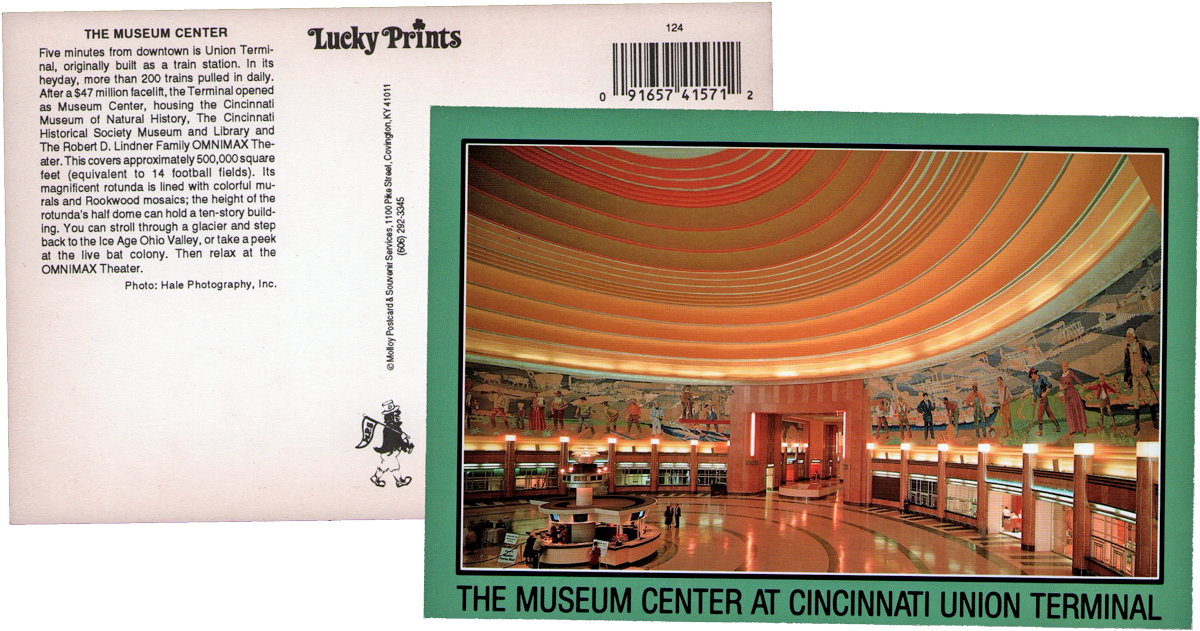

postcard / collection

May 2024 / RWH

Cincinnati, Oh / May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

Cincinnati, Oh / May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

Cincinnati, Oh / May 2024 / RWH

Cincinnati, Oh / May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

Cincinnati, Oh / May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

postcard / collection

Union Terminal's distinctive architecture, interior design, and history have earned it several landmark designations, including as a National Historic Landmark. Its Art Deco design incorporates several contemporaneous works of art, including two of the Winold Reiss industrial murals, a set of sixteen mosaic murals depicting Cincinnati industry commissioned for the terminal in 1931. The main space in the facility, the Rotunda, has two enormous mosaic murals designed by Reiss. Taxi and bus driveways leading to and from the Rotunda are now used as museum space. The now-demolished train concourse held all 16 of Reiss's industrial murals, along with other art and design features.

Union Terminal's distinctive architecture, interior design, and history have earned it several landmark designations, including as a National Historic Landmark. Its Art Deco design incorporates several contemporaneous works of art, including two of the Winold Reiss industrial murals, a set of sixteen mosaic murals depicting Cincinnati industry commissioned for the terminal in 1931. The main space in the facility, the Rotunda, has two enormous mosaic murals designed by Reiss. Taxi and bus driveways leading to and from the Rotunda are now used as museum space. The now-demolished train concourse held all 16 of Reiss's industrial murals, along with other art and design features.

The Winold Reiss industrial murals are a set of 16 tile mosaic murals displaying manufacturing in Cincinnati, Ohio. The works were created by Winold Reiss for Cincinnati Union Terminal from 1931 to 1932, and made up 11,908 of the 18,150 square feet of art in the terminal. The murals were first installed in the train concourse of the terminal, which was demolished in 1974. Prior to the demolition, almost all were moved to the Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport, nine of which were placed in air terminals which were themselves demolished in 2015. The nine works were then relocated to the exterior of the Duke Energy Convention Center, where they stand today. Two murals depicting the Rookwood Pottery Company never left the terminal; they were moved to the Cincinnati Historical Society's special exhibits gallery in 1991.

The Winold Reiss industrial murals are a set of 16 tile mosaic murals displaying manufacturing in Cincinnati, Ohio. The works were created by Winold Reiss for Cincinnati Union Terminal from 1931 to 1932, and made up 11,908 of the 18,150 square feet of art in the terminal. The murals were first installed in the train concourse of the terminal, which was demolished in 1974. Prior to the demolition, almost all were moved to the Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport, nine of which were placed in air terminals which were themselves demolished in 2015. The nine works were then relocated to the exterior of the Duke Energy Convention Center, where they stand today. Two murals depicting the Rookwood Pottery Company never left the terminal; they were moved to the Cincinnati Historical Society's special exhibits gallery in 1991.

May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

May 2024 / RWH

postcard / collection

May 2024 / RWH

Lagniappe

Art Deco Era

image and artwork RWH

Terminal Tetris

May 2024 / RWH

Snapshots

Snapshots

Cincinnati, Oh / May 2024 / RWH

Links / Sources

- Cincinnati Union Terminal Museum Center website

- Amtrak's Cincinnati Union Terminal page

- Great American Stations Cincinnati Union Terminal page

- Wikipedia article for Cincinnati Union Terminal

- The Glass Storybook and the Great Menagerie: The Art of Union Terminal